Backstage with Julia (6 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

I walked up the few steps and knocked. A uniformed guard immediately opened the door.

"I'm Nancy Barr," I said, and then, just to be sure he didn't think I was one of the groupies who regularly hangs around outside the studio hoping for autographs, I told him I was with Julia. But he didn't need more than my name. "They're expecting you," he said, stepping back to let me pass.

Walking me the few steps across the narrow foyer, he led me into a small room. "This is the greenroom. You can wait here and I'll call someone to escort you into the studio." In no time at all, a young woman, perhaps a production assistant or an intern, arrived and led me down a short corridor, through a heavy door, and into the dimly lit studio.

Stepping over the jumble of heavy cables on the floor and peering though the army of cameras standing quietly, I saw the

Good Morning America

living room set that I had seen so many times on television. The studio itself was immense, and the suite of comfortable living room furniture arranged in one corner of that enormous space seemed dollhouse-like with all the production equipment hovering around it.

"They're in the kitchen," my guide informed me, and led me all the way through the studio to a hallway behind it. There were two kitchens at the

Good Morning America

studios. What television viewers saw was a small on-set kitchen that sat on a slightly raised platform behind the set's living room. Off the short hallway behind the studio was a staff kitchen, so small it could have been mistaken for a glorified utility closet had it not been for the four-burner electric stove, refrigerator, single sink, and about two feet of counter space. We could work on the set's kitchen before the show started at seven and again after nine when it went off the air. All other times, we would have to crowd ourselves into the dimensionally challenged room.

My pears and I entered the room where our team was assembled and nibbling on an assortment of items selected from what I discovered was a large buffet set up behind the studio. Paul was reading the newspaper and working his way down a banana. He ate one every single morning, claiming it was good for the constitution. Since he lived into his nineties, I have no reason to doubt him. Liz was sitting on a stool by the phone, also reading a paper, and I wondered if she traveled with her own seating.

"Well, here she is!" Julia hooted enthusiastically, exhibiting that most wonderful way she had of making people feel so happy that they had arrived.

"I am," I said just as enthusiastically. I saw that there was already a large pile of pears on the counter, and I added my every-bit-as-good-looking crop to them, glad to have the perfect-pear mission accomplished.

"Thank you," was all Julia said, "they're perfect." It would be some months before I understood that even if my pears had failed to pass muster, that would not have meant that I did too. Julia saw cooking as an ongoing learning experienceâif you fumbled here and there, if your pears were lousy, she'd definitely let you know, but it would not cost you your job or diminish your competence in her eyes as long as you were willing to learn.

"Now here, meet Sonya," Julia said, directing my attention to her producer, Sonya Selby-Wright. Sonya was in her mid-forties, British, and had been producing for

GMA

for four years, during which time she developed a particular talent for producing food spots. She was blond and fair-complexioned and appeared to be a delicate, fragile person, but, as I would soon discover, she was an effective, insightful producer who had the ability to draw out Julia's natural ability for making instruction entertaining. Julia had a very strong-willed personality, and over the years I would see that she always did her best work with someone who was strong enough to take charge. Russ Morash was a genius at producing and directing her, with no equal, but Sonya was very good.

My first day of work at

Good Morning America

was my initiation to what it took to produce a television food spot. Sonya, Sara, and Julia introduced me to the smoke and mirrors of television cookingâthe swap or swap-out, a crucial component of the short cooking segment. On a half-hour-long cooking show, depending on the recipe, it is possible to demonstrate a dish from start to finish. Rachael Ray does this on her Food Network program

30 Minute Meals

. But unless it is the simplest of recipes or a single technique, this is not possible in the two or three minutes that morning television allots the talent. Therefore, the swap. A typical breakdown for a rice pilaf, for example, would begin with the talent mincing onions, carrots, and celery for a mirepoix. She'd then put the vegetables into a saucepan with melted butter, stir them around a bit, and explain that they must be sautéed slowly until translucent. There wouldn't be enough time to show the transition from raw to translucent, so she switches from that pan to an identical one sitting on the stove with an already cooked mirepoix and pours in a cup of rice. After a few seconds of sautéing the rice, the talent pours in stock, adds seasonings, and covers the pan. The pilaf then needs fifteen minutes to cook, fifteen minutes morning television can't provide, so the talent swaps to an identical pan containing perfectly cooked rice that is also on the stove. She uncovers it, shows the audience what the pilaf looks like fully cooked, perhaps transfers it to a serving dish or a plate that holds meat and vegetables, and in Julia's case says, "Bon appétit." Some recipes require several swaps, and it takes careful planning to know where the switches are most effective so that viewers get a good, clear idea of what is happening and can confidently say to themselves, "I can do that!" or, better yet, "I

want

to do that!"

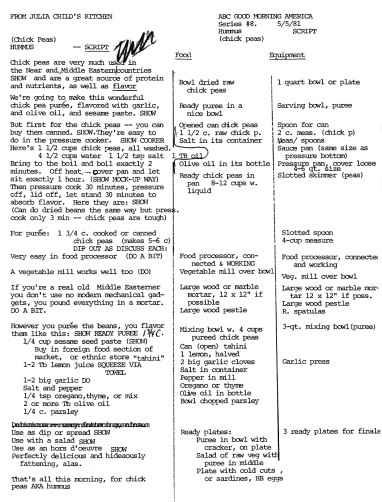

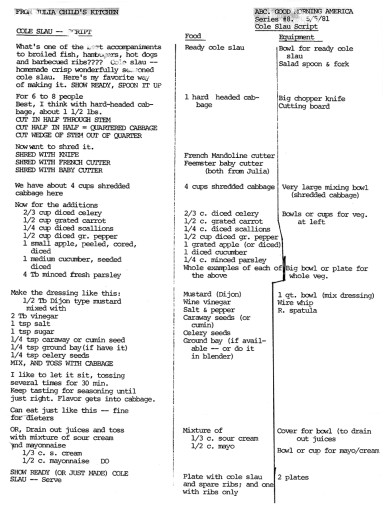

Julia was a master at breaking recipes down into the necessary steps to entice the audience into trying them. She hated what she called "dump TV"âa cooking spot in which the talent dumps the unidentifiable contents of several bowls into a pan and then proclaims it will look like the dazzling finished dish all nicely decorated with hibiscus blooms that sits on the counter. She wanted to show the steps, explain the techniques, produce sizzling sounds, and create some steam. Consequently, her demonstrations usually involved a number of swaps, which she carefully spelled out in her scripts.

Sonya introduced me to blocking, which is planning where the equipment and food will sit on the set when the spot was on air. I had no idea such a thing was necessary but soon realized that blocking is as vital a step in food television as it is in theater and movies, and one that Sonya worked on with the diligence of any Broadway stage director. Before the show went on the air, we brought all the food and equipment to the set and walked through what the talent would do with it. We decided where the items should be laid out, put them there, pretended to cook them, and then laid them out again until we decided where they best worked. Then we drew pictures of the layout and took everything away, transferring then to carefully marked trays. Nothing could stay on the kitchen set during the first two and a half hours of the show. In the brief time of a commercial break, we would have to return everything to the set, and we couldn't bring it there. Union rules demanded that stagehands move the items from the prep kitchen to the set, hence our need to mark the trays as to the position. The blocking and rehearsal meant that when the spot was on the air the talent would not have to move repeatedly back and forth, making it difficult for the cameras and audience to focus on the food. It thwarted any need to reach awkwardly over a hot stove or across the host's midsection to pick something up. It also ensured that tall items would not block shorter ones from the camera's view.

Every time I watched another morning show's production and saw a chef zigzagging around the set or I struggled to see an unidentifiable object hidden behind a tall bottle of wine or olive oil, I thought about how Sonya's diligent blocking never would have allowed it to happen.

From seven until shortly after eight-thirty, while the show was on the air, we crowded into the prep kitchen, working over and around each other under a sign on the wall that said, "Clean up after yourself. Your mother doesn't work here." When the kitchen monitor alerted us to the commercial break, several stagehands picked up the marked trays and carried them to the set. Sonya, Sara, and I followed right behind them and moved the items from the trays to their designated places, obsessively checking to be sure that everything was there and exactly where it should be. There is no wiggle room in live television: if something is missing, the talent has to wing it. Winging it was never a problem for Julia; she was truly unflappable. On one of our earliest shows, Julia sautéed veal cutlets and made a lovely pan sauce for them. Joan Lunden was by her side, and the spot endedâas always, unless it was oysters, which Joan wouldn't touchâwith tasting the finished dish and making appropriate appreciative sounds. Julia put the veal on a plate, napped it with the sauce, and handed it to Joan. Joan looked down, turned to the right and then the left, and then glanced back at Julia. Somehow, in spite of all our careful blocking and obsessive planning, we had forgotten to put a fork and knife on the set. As I stood on the sidelines, wondering in horror if I could crawl under the camera's line of vision and pass utensils up to them, Julia picked up the large wooden spoon she had used to stir the sauce and told Joan, "This will work." Joan struggled a bit to cut the veal, managed to remove a small piece, and ate it with the spoon, which was considerably larger than her mouth. Neither she nor Julia behaved as though it were anything unusual.

Once the live shows were off the air, we began our prep for the next day's tapings. Stagehands set up several long tables in the studio and we went to work dirtying more dishes and preparing more food than I had ever seen in one place before. Taped segments involve so much more preparation than live ones, since no matter how wrong live segments may go, they will happen once only. With taped segments, the director or producer can ask for a retake, so we needed enough food for at least three backupsâthree for every swap. The same rice pilaf recipe that needed two cups of rice to make the swap in a live segment required eight cups to allow for backups in a taped segment.

And that's just one recipe. We were doing five or six. That meant a lot of food, a lot of equipment, nonstop work, and always more cafeteria trays and little glass bowls than we could seem to muster up. And if we weren't going out for lunch, Julia always insisted that we stop at noon and sit down together for a "nice, proper meal" with carefully prepared foodâand wine! Using whatever food we didn't need for the tapings, we'd prepare handsome meals to which Julia often invited guestsâcookbook authors and teachers, several family members, her editor, Judith Jones, and, to the delight of all of us, her dear friend and colleague Jim Beard. The work it took to ready the food for shows

and

prepare a sit-down lunch for eight to twelve people was a bit staggering. In fact, Julia often looked over the mounds of food and nonstop chopping, peeling, and mixing and pronounced with obvious glee, "We're a regular sweatshop." But those meals were what food was about for Julia. It was not a vehicle to stardom or something to fill the pages of a cookbook. It was about the joys of sitting down at a table, sharing, and communicating. The fame she achieved was firmly rooted in the passion she felt about dining well with good friends.