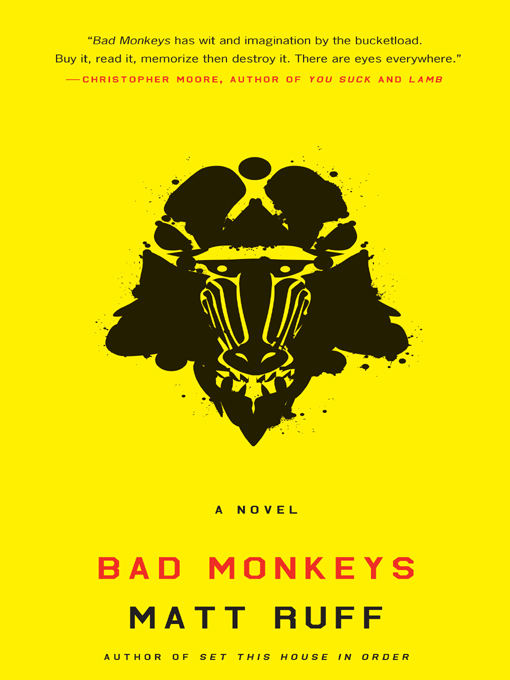

Bad Monkeys

Authors: Matt Ruff

MATT RUFF

For Phil

Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let us go out to the field…”

—Genesis 4:8

Conscience: the inner voice that warns us someone may be looking.

—H. L. Mencken

IT’S A ROOM AN UNINSPIRED PLAY

-wright might conjure while staring at a blank page: White walls. White ceiling. White floor. Not featureless, but close enough to raise suspicion that its few contents are all crucial to the upcoming drama.

A woman sits in one of two chairs drawn up to a rectangular white table. Her hands are cuffed in front of her; she is dressed in an orange prison jumpsuit whose bright hue seems dull in the whiteness. A photograph of a smiling politician hangs on the wall above the table. Occasionally the woman glances up at the photo, or at the door that is the room’s only exit, but mostly she stares at her hands, and waits.

The door opens. A man in a white coat steps in, bringing more props: a file folder and a handheld tape recorder.

“Hello,” he says. “Jane Charlotte?”

“Present,” she says.

“I’m Dr. Vale.” He shuts the door and comes over to the table. “I’m here to interview you, if that’s all right.” When she shrugs, he asks: “Do you know where you are?”

“Unless they moved the room…” Then: “Las Vegas, Clark County Detention Center. The nut wing.”

“And do you know why you’re here?”

“I’m in jail because I killed someone I wasn’t supposed to,” she says, matter-of-factly. “As for why I’m in this room, with you, I guess that has something to do with what I told the detectives who arrested me.”

“Yes.” He gestures at the empty chair. “May I sit down?”

Another shrug. He sits. Holding the tape recorder to his lips, he recites: “June 5th, 2002, approximately nine forty-five a.m. This is Dr. Richard Vale, speaking with subject Jane Charlotte, of…What’s your current home address?”

“I’m kind of between homes right now.”

“…of no fixed address.” He sets the tape recorder, still running, on the table, and opens the folder. “So…You told the arresting detectives that you work for a secret crime-fighting organization called Bad Monkeys.”

“No,” she says.

“No?”

“We don’t fight crime, we fight evil. There’s a difference. And Bad Monkeys is the name of my division. The organization as a whole doesn’t have a name, at least not that I ever heard. It’s just ‘the organization.’”

“And what does ‘Bad Monkeys’ mean?”

“It’s a nickname,” she says. “All the divisions have them. The official names are too long and complicated to use on anything but letterhead, so people come up with shorthand versions. Like the administrative branch, officially they’re ‘The Department for Optimal Utilization of Resources and Personnel,’ but everyone just calls them Cost-Benefits. And the intel-gathering group, that’s ‘The Department of Ubiquitous Intermittent Surveillance,’ but in conversation they’re just Panopticon. And then there’s my division, ‘The Department for the Final Disposition of Irredeemable Persons…’”

“Irredeemable persons.” The doctor smiles. “Bad monkeys.”

“Right.”

“Shouldn’t it be Bad Apes, though?” When she doesn’t respond, he starts to explain: “Human beings are more closely related to great apes than—”

“You’re channeling Phil,” she says.

“Who?”

“My little brother. Philip. He’s a nitpicker, too.” She shrugs. “Yeah, I suppose technically, it should be apes instead of monkeys. And technically”—she lifts her arms and gives her bracelets a shake—“these should be called

wrist

cuffs. But they’re not.”

“So in your job with Bad Monkeys,” the doctor asks, “what is it you do? Punish evil people?”

“No. Usually we just kill them.”

“Killing’s not a punishment?”

“It is if you do it to pay someone back. But the organization’s not about that. We’re just trying to make the world a better place.”

“By killing evil men.”

“Not

all

of them. Just the ones Cost-Benefits decides will do a lot more harm than good if they go on breathing.”

“Does it bother you to kill people?”

“Not usually. It’s not like being a police officer. I mean cops, they have to deal with all kinds of people, and sometimes, upholding the law, they’ve got to come down on folks who really aren’t all that bad. I can see where that would give you a crisis of conscience. But the guys we go after in Bad Monkeys aren’t the sort you have mixed feelings about.”

“And the man you were arrested for killing, Mr.—”

“Dixon,” she says. “He wasn’t a bad monkey.”

“No?”

“He was a prick. I didn’t like him. But he wasn’t evil.”

“Then why did you kill him?”

She shakes her head. “I can’t just tell you that. Even if I thought you’d believe me, it wouldn’t make sense unless I told you everything else first. But that’s too long a story.”

“I don’t have anywhere else I have to be this morning.”

“No, I mean it’s a

long

story. This morning I could maybe give you the prologue; to get through the whole thing would take days.”

“You do understand you’re going to be in here for a while.”

“Of course,” she says. “I’m a murderer. But that’s no reason why you should have to waste your time.”

“Do you want to tell the story?”

“I suppose there’s a part of me that does. I mean, I didn’t have to mention Bad Monkeys to the cops.”

“Well if you’re willing to talk, I’m willing to listen.”

“You’re just going to think I’m crazy. You probably already do.”

“I’ll try to keep an open mind.”

“That won’t help.”

“Why don’t we just start, and see how it goes?” the doctor suggests. “Tell me how you first got involved with the organization. How long have you worked for them?”

“About eight months. I was recruited last year after the World Trade towers went down. But that’s not really the beginning. The first time I crossed paths with them was back when I was a teenager.”

“What happened?”

“I stumbled into a Bad Monkeys op. That’s how a lot of people get recruited: they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, they get caught up in an operation, and even though they don’t really understand what’s happening, they show enough potential that the

organization takes notice. Then later—maybe days, maybe decades—there’s a job opening, and New Blood pays them a visit.”

“So tell me about this operation you stumbled into.”

“Well, it all started when I figured out that the janitor at my high school was the Angel of Death…”

IT WAS THE FALL OF 1979. I WAS

fourteen years old, and I’d been sent away from home to live with my aunt and uncle.

Where was home?

San Francisco. The Haight-Ashbury. Charlie Manson’s old stomping grounds.

Why were you sent away?

Mostly to keep my mom from killing me. We’d been fighting pretty much nonstop all that year, but towards the end of the summer things got especially bad. You know, physical.

What did you fight about?

The usual. Boys. Drugs. Me staying out all night with my friends. Plus there was my brother. My dad had taken off a few years before, and to support us my mom was working twelve-hour days, which she hated, and so I was supposed to watch Phil, which I hated.

How old was Phil?

Ten. Smart ten, I mean he knew enough not to drink Clorox or set fire to the apartment. Plus he was a really internal kid, the kind where if he had a book to read, he’d sit quiet for hours. Which is one reason I resented having to watch him: there was nothing to watch. It was like babysitting a pet rock. So what I’d do instead, a lot

of the time, I’d take Phil out and park him somewhere, go off and do my own thing, and come back later and pick him up. And if my mom got home before us, or if it turned out she’d tried to call in from work to check on us, I’d just make up some story about how I took Phil to the523e zoo—and Phil, he’d back me up, because I’d threatened to sell him to the gypsies if he didn’t.

That worked out OK for a while, but eventually my mother got wise. One time I didn’t bring Phil home until nine o’clock at night, and she knew the zoo wasn’t open that late. Then this other time, I got caught shoplifting at a record store, and by the time I talked my way out of it, the library where I’d left Phil was closing. One of the librarians found him in the stacks and reported him abandoned.

It was after that that my mother and I really went to war with each other. She started calling me her bad seed, saying I must have gotten all my genes from my no-good father. Looking back on it now, I don’t blame her—in her shoes, I’d have done some name-calling too—but at the time, my position was “Hey, I didn’t ask for a little brother, I didn’t volunteer to be deputy mom, and if you think I’m a bad seed now, just wait until I get busy trying to earn the title.”

You say the fights turned physical.

Yeah. Slaps and hair-pulling, mostly. I gave as good as I got—we were about the same size—so it wasn’t like abuse. More like scuffling. She had more anger than me, though, and every so often she’d escalate to weapons: belts, dishes, whatever was handy. And like I say, I gave as good as I got, but long-term, that wasn’t a healthy trend.

What about your brother? What was your mother’s relationship with him like?

Oh, she loved Phil. Of course. He was the low-maintenance kid.

Did she display affection towards him?

She didn’t throw plates at him. Beyond that, I don’t know, maybe she kissed him on the forehead once in a while. I wasn’t jealous, if that’s what you’re asking. The only thing that bugged me about their relationship was having to hang around for it. She expected me to help mind Phil even when she was home, which struck me as totally unreasonable. We had a bunch of fights about that.

Was it one of these fights that led to you being sent away?

No. That was a different incident. Phil was involved, but it wasn’t really about him.

What happened?

It was kind of funny, actually. There was this big vacant lot across from our apartment building that some hippies had turned into a community garden. You could sign up for a plot of ground and raise vegetables or whatever. My friend Moon had some marijuana seeds, so we decided to try growing our own pot there.

In a public garden?

Not the brightest scheme ever, I know. But you have to understand, we’d only ever seen pot in baggies before, so we had no idea how big the plants got. We figured, it’s a

weed,

and weeds are small. We thought we could grow bigger plants around it as cover, and then harvest it before anybody noticed what it was.

So I signed us up for a plot, but under Phil’s name. The garden was one of the places I used to leave him; he didn’t care about plants, but he liked animals, and there were these stray cats there that he could play with. That’s what he was doing, herding cats, the day our marijuana patch got raided.

You’d think the hippies would have been the first to spot it, but it was a beat cop. The guy’s name, I swear to God, was Buster Friendly. Officer Friendly’s vice detector went off as he was walking past the garden one afternoon, and the next thing you know he had every adult in the place up against the fence, and he was waving the

sign-up sheet in their faces, wanting to know which one of them was Phil. Then Phil came up and tugged him on the sleeve, and the officer asked him, “Are those your marijuana plants, son?” and Phil said yes, but without me right there whispering “gypsies” in his ear, he wasn’t a very convincing liar, so it only took about ten minutes for Officer Friendly to get the real story out of him. Ten minutes after that, I came back from Moon’s house to pick up Phil and got nabbed.

Did the officer arrest you?

He took us back to the police station, but he didn’t book us. He ran us through the Scared Straight routine: showed us the holding cell, introduced us to some of the losers they had locked up in there, told us some horror stories about how much worse the actual jail was. Once I realized he wasn’t actually going to do anything to us, I wasn’t impressed, but I pretended like I was, because I figured I might need this guy in my corner once my mom showed up. So I called him “sir” a lot, and tried to come off like a little rascal instead of a little bitch.

Eventually my mom got there, and she went right for me, no preliminaries. By this point I had Officer Friendly halfway liking me, but he still needed me to learn a lesson, so if my mother had just smacked me around a little he would have let it go. But she was in full fury, screaming about the bad seed, and she started, like,

throttling

me, and then I lost my cool and started fighting back, and it turned into this big drama scene, with cops running in from other rooms to help pull us off each other. After they got us separated they called in a social worker, and we had this three-hour encounter session, during which my mom made it clear that if they sent me home with her, she wasn’t just going to send me to bed with no supper, she was going to drown me in the tub. So they had to come up with a Plan B.

What finally happened, my mom agreed to see a shrink for anger management, and in exchange she got

to take Phil home. I stayed at the police station while Officer Friendly went with them to pick up a couple bags of my clothes, and then he drove me out to my aunt and uncle’s place in the San Joaquin Valley. It was the middle of the night by now, and it was at least a hundred-mile drive, but he insisted on taking me himself. So at first I was thinking, wow, he really bought my little-rascal act. And so I kept it up, kept playing him, until at one point I was in the middle of this completely bogus story about my mother, and he gave me this look, and I realized: he sees through me. He

knows

I’m bullshitting him, but he’s cutting me this huge break anyway, not because he’s stupid but because he’s a decent guy. So that shut me up for a while.

Were you grateful, or just embarrassed?

Both. Look, I know what you’re thinking: absent father, and now here’s this male authority figure going out of his way for me, blah blah blah, and there is something to that. But also, him being smarter than I figured, that was a change in plan.

I mean, I had no intention of staying with my aunt and uncle. The way I’d already worked it out in my head, I’d let Officer Friendly drop me off, I’d spend the night, get some breakfast, maybe steal some cash, and take off. Hitchhike back to S.F. and see if Moon’s parents would let me crash at their place. But now it turned out Officer Friendly had a brain, so of course he knew I was planning to do that.

We were almost there when he said to me: “Do me a favor, Jane?” And I said, “What?”, and he said, “Give it two weeks.” And I didn’t have to ask, give

what

two weeks—he definitely had my frequency. So instead I said: “Why two weeks?” And he said, “That should be enough time for you to cool down. Then you can decide whether you really want to do something stupid.” That pissed me off a little, but not as much as I would have expected, and I said, “What are you, my foster dad now?”

and he said, “Is that what it’s going to take?”, which shut me up again for a few seconds. Finally I said, “Twenty bucks,” and he said, “Twenty bucks?” and I said, “Yeah. That’s what it’s going to take.” But he shook his head and said, “For twenty bucks you’ve got to give it at least a month.”

We spent the rest of the ride haggling. A part of me was thinking, this is ridiculous, but in spite of myself I was warming up to the guy, so it was a

serious

haggle. In the end we settled on twenty-five dollars, plus I promised that if I did decide to run away when the month was up, I’d call him first to give him a chance to talk me out of it. Getting me to agree to that last part, that was a sharp move.

How so?

Well, he’d gotten me to like him, right? As much as I liked any adult at that age. But at the same time, I wasn’t stupid either, I knew in his job he must deal with hundreds of kids, most of them a lot more screwed up than me, so who knew if he’d even remember me in a month. And if I did call him up, and he said “Jane

who

?”, I knew I wasn’t going to enjoy that. But a deal’s a deal, so the only way for me to

not

call him was to either not run away, or wait until things got bad enough that I’d feel OK about breaking my word.

So that’s how I ended up at my aunt and uncle’s place. How I ended up

staying

there.

They lived in Siesta Corta, which is Spanish for “wake me if anything happens.” It was a wide spot on the road between Modesto and Fresno, with everything a truck driver or a migrant fruit-picker could ask for: a gas station, a general store, a diner, a bar, a fleabag motel, and a Holy Roller church. My aunt and uncle ran the general store.

What sort of people were they?

Old. They were my aunt and uncle on my father’s side. My father had been fifteen years older than my

mother, and my aunt was his older sister, so to look at her you’d think she was my grandmother. My uncle was even older.

Was it awkward for you, staying with your father’s sister?

Not really. My father was completely out of the picture at this point; he’d cut ties with the rest of his family the same time he walked out on us. And my aunt wasn’t anything like him. She’d been married to my uncle and living in the same house since the end of World War II.

How did they feel about you coming to live with them?

If there’d been some other option, I don’t think they’d have volunteered to let me stay with them as long as I did, but they never complained about it.

So you got along with them?

I didn’t really have a choice. They were the most nonconfrontational people I’d ever met: you couldn’t pick a fight with them if you tried. And it’s not that they didn’t have rules, but their way of getting you to behave was to make it impossible for you not to.

Like my uncle, right, he was the kind of guy who liked to have a glass of whiskey before he went to bed. I thought that was a pretty good idea, so the second night I was there, I snuck into his study after he went to sleep and helped myself. And I didn’t take much, but the thing about guys who drink every day, they know exactly what’s left in the bottle they’re working on, and if the level is off by even a quarter inch, they notice.

Now, if my mom had caught me drinking, especially her stuff? She’d have been in my face about it in two seconds flat. My uncle never said a word—but the next day, I passed by the study and heard drilling inside, and that evening when I went to fix myself another nightcap I found a brand-new lock on the liquor cabinet. A

big

lock, fist-sized, the kind you can’t pick.

They were like that with every bad thing I did. They never lectured me; they assumed I knew right from

wrong, but if I insisted on doing wrong, they found some way to lock out that choice.

One morning my aunt asked me if I’d like to come help out at the store. Normally there’d have been no chance, but I was already so bored that I said OK. At the end of the day she gave me fifty cents, which seemed pretty cheap for eight hours, even if I did spend most of that time flipping through magazines. Next day, same deal. The day after that, I bailed out around noon, and instead of waiting to get paid I swiped a couple dollars from the till. Then that night before bed, I went to put the two bucks into the drawer where I kept my other wages and my Officer Friendly money, and instead of the twenty-six dollars that should have been there, I only found twenty-four. It was obvious what had happened, but I pulled the drawer out anyway and shook it upside-down, just in case the rest of the money had gotten stuck somehow. A single quarter fell out.

Your pay for the half-day you’d just worked?

Right.

Did you say anything to your aunt?

What would I have said? No fair stealing back what I stole from you? Anyway I had to hand it to her, keeping a step ahead of me that way. And no energy wasted on yelling. It seemed, I don’t know,

efficient.

But it was also frustrating. If I haven’t made it clear already, there wasn’t a lot for me to do in Siesta Corta, and once you took away the stuff I

shouldn’t

be doing, life got really dull really fast.

The low point came about ten days in. My aunt and uncle didn’t own a TV—of

course

they didn’t—but they did have a lot of books in the house, and one day in desperation I started rooting through their library. Now I don’t want to give you the wrong impression. I wasn’t illiterate, and I wasn’t allergic to books the way some people are, but still, on my list of preferred leisure ac

tivities, reading anything more demanding than

Tiger Beat

ranked somewhere down around badminton and pulling taffy. But there I was, on a perfectly good Friday afternoon, curled up in an easy chair with a Nancy Drew mystery in my lap.