Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients (20 page)

Read Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

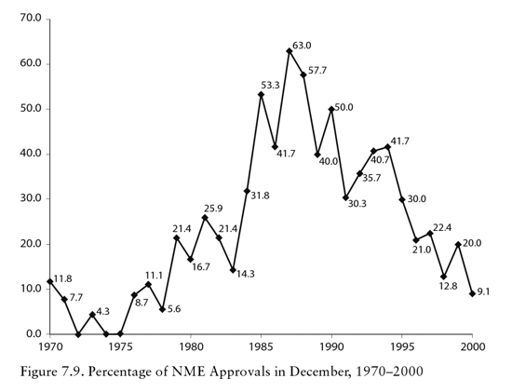

These kinds of pressures can also be seen in the approval times for medicines, which have fallen hugely around the world: in the US they have reduced by half since 1993, on the back of previous cuts before that; and in the UK they dropped even more dramatically, from 154 working days in 1989 to forty-four days just a decade later.

It would be a mistake to imagine that drug companies are the only people applying pressure for fast approvals. Patients can also feel they are being deprived of access to drugs, especially if they are desperate. In fact, in the 1980s and 1990s the key public drive for faster approvals came from an alliance forged between drug companies and AIDS activists such as ACT UP.

At the time, HIV and AIDS had suddenly appeared out of nowhere, and young, previously healthy gay men were falling ill and dying in terrifying numbers, with no treatment available. We don’t care, they explained, if the drugs that are currently being researched for effectiveness might kill us: we want them, because we’re dying anyway. Losing a couple of months of life because a currently unapproved drug turned out to be dangerous was nothing, compared to a shot at a normal lifespan. In an extreme form, the HIV-positive community was exemplifying the very best motivations that drive people to participate in clinical trials: they were prepared to take a risk, in the hope of finding better treatments for themselves or others like them in the future. To achieve this goal they blocked traffic on Wall Street, marched on the FDA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland, and campaigned tirelessly for faster approvals.

As a result of this campaign, a series of new regulations were implemented to allow accelerated approval of certain new drugs. This legislation was intended for use on lifesaving drugs, in situations where there was no currently available medical treatment. Unfortunately, now that they have been in place for more than a decade, we can see that this is not how they have been used.

Midodrine

Once a drug has been approved it is very rare for a regulator to remove it from the market, especially if the only issue is lack of efficacy, rather than patients actively dying because of side effects. Where they do finally make such a move, it is usually after phenomenal delay.

Midodrine is a drug used to treat ‘orthostatic hypotension’, a drop in blood pressure causing dizziness when you stand up.

26

While this is doubtless unpleasant for those who experience it, and there may be an increased risk of, say, falls when feeling dizzy, this condition is generally not what most people would regard as serious or life-threatening. Furthermore, the extent to which it is regarded as a singular medical problem varies between countries and cultures. But because there were no previous drugs available to treat it, midodrine was able to be approved through the accelerated programme, in 1996, with weak evidence, but the promise of better studies to follow.

Specifically, midodrine was approved on the basis of three very small, brief trials (two of them only two days long) in which many of the people receiving the drug dropped out of the study completely. These trials showed a small benefit on a surrogate outcome – changes in blood-pressure recordings when the participants stood up – but no benefit on real-world outcomes like dizziness, quality of life, falls, and so on. Because of this, after midodrine was approved through the urgent approval scheme, the manufacturer, Shire, had to promise it would do more research once the drug was on the market.

Year after year, no satisfactory trials appeared. In August 2010,

fourteen years later

, the FDA announced that unless Shire finally produced some compelling data showing that midodrine improved actual symptoms and day-to-day function, rather than some numbers on a blood-pressure machine after one day, it would take the drug off the market for good.

27

This seemed like an assertive move which should finally provoke compliance, but the result was quite the opposite. Effectively, the company said: ‘Fine.’ The drug was off patent: anyone could make it, and indeed Shire now only made 1 per cent of the midodrine sold, with Sandoz, Apotex, Mylan and other companies making the rest. In such a crowded market there was very little money to be made from selling this medicine, and certainly no incentive to invest in research that would only help other companies sell a hundred times more of the same product. Fourteen years on from midodrine’s original approval, the FDA found that there is such a thing as being simply too late.

But that was not the end of the story. Suddenly a vast army of midodrine users and special-interest patient groups appeared, with politicians at their helm: 100,000 patients had filed prescriptions for the drug in 2009 alone. To them, this pill was a life-saver, and the only drug available to treat their condition. If all companies were going to be banned from making it, with the drug taken off the market, this would be a disaster. The fact that no trial had ever demonstrated any concrete benefit was irrelevant: quack remedies such as homeopathy continue to maintain a viciously loyal fan base, despite the fact that homeopathic pills by definition contain no ingredients at all, and despite research overall showing them to perform no better than placebo.

*

These midodrine patients didn’t care about what trials found: they ‘knew’ that their drug worked, with the certainty of true believers. And now the government was planning to take it away because of some complicated administrative transgression. Surrogate what? This must have sounded like irrelevant word-play from where they were trying to stand.

The FDA was forced to backtrack, and leave the drug on the market. Slow negotiations have continued over the post-marketing trials, but the FDA now has very little leverage with any company over this drug. Almost two decades after midodrine was first approved as an urgent, exceptional case, the drug companies are still making promises to do proper trials. As of 2012, these trials are nowhere to be seen.

This is a serious problem, and it goes way beyond this single, rather trivial medicine. The General Accounting Office is the investigative audit branch of the US Congress. In 2009, it examined the FDA’s failure to chase these kinds of post-approval studies, and its findings were damning: between 1992 and 2008, ninety drugs had been given accelerated approval on the basis of surrogate endpoints alone, with the drug companies making a commitment to conduct 144 trials in total. As of 2009, one in every three of those trials was still outstanding.

28

No drug had

ever

been taken off the market because its manufacturer had failed to hand over outstanding trial data.

The British academic John Abraham is a social scientist who has done more than anyone to shine a light into the traditions and processes of regulators around the world. He has concluded that accelerated approval is simply part of a consistent trend towards deregulation, for the benefit of the industry. It’s useful to walk through just one of the case studies he has worked on, with colleague Courtney Davis, to see how regulators around the world dealt with the

best

possible candidates for these urgent assessments.

29

Gefitinib (brand name Iressa) is a cancer drug made by AstraZeneca, for desperate patients who have reached the end of the line. It’s approved for non-small-cell lung cancer, which is a serious life-threatening diagnosis, and it’s approved for use as ‘third-line’ treatment, after all else has failed. Its accelerated approval was driven partly by patient campaigning, just like the AIDS campaigners who drove the introduction of accelerated approval legislation in the first place. It’s also a good case study, because the manufacturer did actually conduct its follow-up studies, which is fairly unusual (only 25 per cent of the cancer drugs being studied by Abraham have done so).

For standard approval of a lung-cancer treatment you need to show meaningful improvement in either survival or symptoms. But ‘tumour response’ – a reduction in tumour size seen on a body scan – is a fairly typical surrogate outcome for cancer drugs, which can be used to get accelerated approval; after doing so, you will then need to do more trials to find out if this translates into benefits that actually matter to patients.

Initially, AstraZeneca provided evidence from a small trial showing a 10 per cent drop in tumour size on Iressa. This was regarded by the FDA as unimpressive, especially since the patients in the trial were unusual, with slower-growing tumours than you’d usually see. But the company pressed on, and began much larger trials measuring the impact on survival. It had expected to finish these studies after the drug was rapidly approved, but in fact they were completed before then. The trials on real-world outcomes found no survival benefit. What’s more, contradicting the smaller, earlier study, they found no improvement in tumour size. One FDA scientist summarised the findings fairly bluntly: ‘It’s 2,000 patients saying Iressa doesn’t work versus 139 saying it works marginally.’

At the same time, the company was also giving the drug to 12,000 desperate, dying patients with no other option, through something known as an ‘expanded access programme’. This is common when patients have shown no response to any other medication, and are regarded as too unfit for clinical trials (although I would argue that trials should ideally include everyone eligible for treatment, since we only do them to try to answer the question of whether a drug works in real-world patients). These programmes can cost companies money, but they also generate a huge amount of goodwill from desperate people, their families and their organised patient groups.

Regulators now, like so many public bodies, set high store by ‘public engagement’, and this is an admirable goal, if done well. But what we see here is not an example of good public engagement. Large, well-conducted, fair tests of Iressa had shown that it was no better than a dummy sugar pill containing no medicine. Yet many dying patients from the expanded access programmes, who had been given the drug for free, travelled with advocacy groups to give compelling evidence to the FDA. From their perspective this was ‘a wonderful drug’, they explained, ‘light-years better than previous treatment’. It ‘began to eliminate cancer symptoms in seven days’. Tumours were ‘90 per cent gone in three months’, said one. Whether that was exaggeration or fluke, the reality is that fair tests showed no benefit. But the desperate patients disagreed, and asserted their case plainly and simply: Iressa ‘will save lives’. This personal testimony was in all likelihood a combination of the placebo effect and the natural fluctuation in symptoms that all patients experience. That didn’t seem to matter.

When the committee charged with approving the drug cast their votes, they went 11–3 in favour.

It’s hard to know what to make of this process, since the vote went against not only the surrogate outcome data, but also the evidence from very large trials showing no benefit on real-world outcomes or survival. But we are all human, and it is hard to reject a drug when you’re faced with moving life-and-death testimony. One FDA scientist told John Abraham during his field work: ‘[Patient testimonials] definitely have an influence over advisory committees. That’s what Iressa proves.’ Several of these patients had been funded to attend the FDA advisory committee meeting by AstraZeneca. We can only wonder if individuals who had not been successfully treated with Iressa would have been flown across the country to speak their personal truth. Perhaps not. Perhaps they might be dead.

The FDA could have rejected the view of its expert committee, and that might have been wise. Not only was there no evidence of benefit: there were reports from Japan of fatal pneumonia associated with Iressa, affecting 2 per cent of patients, a third of whom died within a fortnight. But the FDA approved the drug all the same. AstraZeneca was compelled to conduct a further 1,700-patient study, which again found no benefit over placebo. Iressa stayed on the market. Another treatment appeared, and this one was effective in third-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Iressa stayed on the market.

The FDA did send out a letter saying that no new patients should be started on Iressa, but drugs that are on the market get used by doctors, often quite haphazardly, driven by marketing, habit, familiarity, rumour and lack of clear current information. Iressa continued to be prescribed for new patients. And still it stayed on the market.

We can see from the percentages in surveys that post-marketing trials requested by regulators are often neglected; and cynical doctors will often tell you that ineffective drugs are commonly marketed. But midodrine and Iressa are, I think, two cases that really put flesh on those bones. Accelerated approval is

not

used to get urgent drugs to market for emergency use and rapid assessment. Follow-up studies are not done. These accelerated approval programmes are a smokescreen.

The impact on innovation

As we have seen, drugs regulators don’t require that new drugs are particularly good, or an improvement on what came before; they don’t even require that drugs are particularly effective. This has interesting consequences on the market more broadly, because it means that the incentives for producing new drugs that improve patients’ lives are less intense. One thing is clear from all the stories in this book: drug companies respond rationally to incentives, and when those incentives are unhelpful, so are drug companies.