Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients (41 page)

Read Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

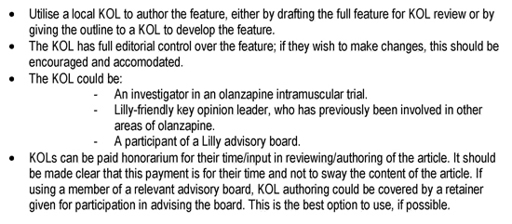

Then it discusses choosing an appropriate ‘author’:

What happens once a paper is in progress? For this, let’s switch to another study, on an antidepressant called paroxetine. You can read all of these documents and more at the Drug Industry Document Archive, built by the University of California, San Francisco, to house materials released during legal cases involving the pharmaceutical industry.

83

Professor Martin Keller of Brown University is discussing the content of ‘his’ paper with a PR person working for the drug company GSK: ‘You did a superb job with this, thank you very much. It is excellent. Enclosed are some rather minor changes from me.’

84

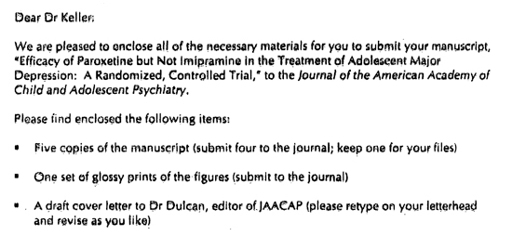

The ghostwriter gets back to him with everything nicely organised and ready to go, because, of course, the academic must be the one who sends the paper to the journal.

85

You will remember the earlier description of what a time-consuming hassle it is for an academic to pull a paper together and submit it to a journal themself. When you’re working with GSK, this is all rather more straightforward: ‘Please retype on your letterhead and revise as you like.’

And so it goes. To some academics – to those in the know, and on the key opinion leader circuit – this has all become so commonplace, so obvious, that they have even used it to try to dodge responsibility for the content of the papers on which their name appears. After a crucial study on the painkiller drug Vioxx was found to have failed adequately to describe the deaths of patients receiving it,

86

the first author told the

New York Times

: ‘Merck designed the trial, paid for the trial, ran the trial…Merck came to me after the study was completed and said, “We want your help to work on the paper.” The initial paper was written at Merck, and then it was sent to me for editing.’ Well that’s OK, then.

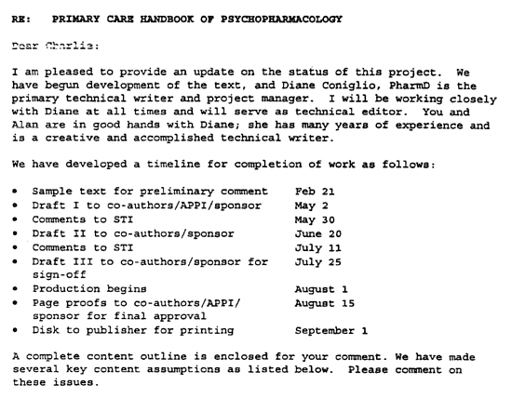

It doesn’t stop at journal articles. Medical writing company STI, for example, wrote a whole physician textbook which appeared with the names of two senior doctors on it.

87

If you follow through the documentation, now in the public domain, a draft of the textbook says it was paid for by GSK, and written by two staff members at the medical writing company they paid. But in the preface to the final published textbook, the doctors whose names appear on the cover merely thank STI for ‘editorial assistance’, and GSK for ‘an unrestricted educational grant’.

Dr Charles Nemeroff, one of the ‘authors’ of this textbook, responded to these allegations in the

New York Times

in 2010. He said he conceptualised the book, wrote the original outline, reviewed every page, and the company had ‘no involvement in content’.

88

So you can draw your own conclusions, I’ve included, below, a scan of the letter sent to Nemeroff at the outset of the project by the writing company.

89

I promise this is the last time I’ll print such documents, but they are so refreshingly explicit. To my eyes, this letter features STI, the commercial writers employed by GSK, saying things like ‘We have begun development of the text’, and ‘A complete content outline is enclosed for your comment.’ There’s also a timeline, according to which the manuscript is repeatedly sent to the sponsor for ‘sign-off’ and ‘approval’.

So, the person conducting a study, analysing the data, writing a paper, steering it into the hands of a journal, and even writing your medical textbook, may not be quite who you imagine.

As a result of all this, as we’ve seen, key opinion leaders who favour the industry’s drugs are given shining CVs and rise to ever higher academic status, conferring even more independent kudos on the treatments they prefer. The academic literature is overwhelmed with repetitive and unsystematic discussion papers, acting as covert promotional literature rather than genuine academic contributions. It is also distorted, with publications that repeatedly reframe treatments in ways that the industry prefers. Even if they’re not promoting just one drug, this means that academics working on commercial areas of medicine, those involving new pills, have an increased prominence compared to those who don’t have professional writers to do their donkeywork for them. So people studying social factors, or lifestyle changes, or side effects, or medicines that are out of patent, are edged out.

It goes without saying that when we’re dealing with medical treatments, which can be hugely harmful as well as helpful, it’s vitally important that all our information is reliable, and transparent. But there is another ethical dimension, which often seems to be neglected.

These days, in most universities, we send a long and threatening document to every undergraduate student, explaining how every paragraph of every essay and dissertation they submit will be put through a piece of software called TurnItIn, expensively developed to detect plagiarism. This software is ubiquitous, and every year its body of knowledge grows larger, as it adds every student project, every Wikipedia page, every academic article, and everything else it can find online, in order to catch people cheating. Every year, in every university, students are caught receiving undeclared outside help; every year, students are disciplined, with points docked and courses marked as ‘failed’. Sometimes they are thrown off their degree course completely, leaving a black mark of intellectual dishonesty on their CV forever.

And yet, to the best of my knowledge, no academic anywhere in the world has ever been punished for putting their name on a ghostwritten academic paper. This is despite everything we know about the enormous prevalence of this unethical activity, and despite endless specific scandals around the world involving named professors and lecturers, with immaculate legal documentation, and despite the fact that it amounts, in many cases, to something that is certainly comparable to the crime of simple plagiarism by a student.

Not one has ever been disciplined. Instead, they have senior teaching positions.

So, what do the regulations say about ghostwriting? For the most part, very little. A survey in 2010 of the top fifty medical schools in the United States found that all but thirteen had no policy at all prohibiting their academics putting their name to ghostwritten articles.

90

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, meanwhile, has issued guidelines on authorship, describing who should appear as a named author on a paper, in the hope that ghostwriters will have to be fully declared as a result. These are widely celebrated, and everyone now speaks of ghostwriting as if it has been fixed by the ICMJE. But in reality, as we have seen so many times before, this is a fake fix: the guidelines are hopelessly vague, and are exploited in ways that are so obvious and predictable that it takes only a paragraph to describe.

The ICMJE criteria require that someone is listed as an author if they fulfil three criteria: they contributed to the conception and design of the study (or data acquisition, or analysis and interpretation); they contributed to drafting or revising the manuscript; and they had final approval on the contents of the paper. This sounds great, but because you have to fulfil

all three

criteria to be listed as an author, it is very easy for a drug company’s commercial medical writer to do almost all the work, but still avoid being listed as an author. For example, a paper could legitimately have the name of an independent academic on it, even if they only contributed 10 per cent of the design, 10 per cent of the analysis, a brief revision of the draft, and agreed the final contents. Meanwhile, a team of commercial medical writers employed by a drug company on the same paper would not appear in the author list, anywhere at all, even though they conceived the study in its entirety, did 90 per cent of the design, 90 per cent of the analysis, 90 per cent of the data acquisition, and wrote the entire draft.

91

In fact, often the industry authors’ names do not appear at all, and there is just an acknowledgement of editorial assistance to a company. And often, of course, even this doesn’t happen. A junior academic making the same contribution as many commercial medical writers – structuring the write-up, reviewing the literature, making the first draft, deciding how best to present the data, writing the words – would get their name on the paper, sometimes as first author. What we are seeing here is an obvious double standard. Someone reading an academic paper expects the authors to be the people who conducted the research and wrote the paper: that is the cultural norm, and that is why medical writers and drug companies will move heaven and earth to keep their employees’ names off the author list. It’s not an accident, and there is no room for special pleading. They don’t want commercial writers in the author list, because they know it looks bad.

Is there a solution? Yes: it’s a system called ‘film credits’, where everyone’s contribution is simply described at the end of the paper: ‘X designed the study, Y wrote the first draft, Z did the statistical analysis,’ and so on. Apart from anything else, these kinds of credits can help to ameliorate the dismal political disputes within teams about the order in which everyone’s name should appear. Film credits are uncommon. They should be universal.

If I sound impatient about any of this, it’s because I am. I like to speak with people who disagree with me, to try to change their behaviour, and to understand their position better: so I talk to rooms full of science journalists about problems in science journalism, rooms full of homeopaths about how homeopathy doesn’t work, and rooms full of people from big pharma about the bad things they do. I have spoken to the members of the International Society of Medical Publications Professionals three times now. Each time, as I’ve set out my concerns, they’ve become angry (I’m used to this, which is why I’m meticulously polite, unless it’s funnier not to be). Publicly, they insist that everything has changed, and ghostwriting is a thing of the past. They repeat that their professional code has changed in the past two years. But my concern is this. Having seen so many codes openly ignored and broken, it’s hard to take any set of voluntary ideals seriously. What matters is what happens, and undermining their claim that everything will now change is the fact that nobody from this community has ever engaged in whistleblowing (though privately many tell me they’re aware of dark practices continuing even today). And for all the shouting, this new code isn’t even very useful: a medical writer could still produce the outline, the first draft, the intermediate drafts and the final draft, for example, with no problem at all; and the language used to describe the whole process is oddly disturbing, assuming – unthinkingly – that the data is the possession of the company, and that it will ‘share’ it with the academic.

But more than that, even if we did believe that everything has suddenly changed, as they claim, as everyone in this area always claims – and it will be half a decade, at least, as ever, before we can tell if they’re right – not one of the longstanding members of the commercial medical writing community has ever given a clear account of why they did the things described above with a clear conscience. They paid guest authors to put their names on papers they had little or nothing to do with; and they ghostwrote papers covertly, knowing exactly what they were doing, and why, and what effect it would have on the doctors reading their work. These are the banal, widespread, bread-and-butter activities of their industry. So, a weak new voluntary code with no teeth from people who have not engaged in full disclosure – nor, frankly, offered an apology – is not, to my mind, any evidence that things have changed.