Bad Science (6 page)

Authors: Ben Goldacre

Tags: #General, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Errors, #Health Care Issues, #Essays, #Scientific, #Science

So now you can see, I would hope, that when doctors say a piece of research is “unreliable,” that’s not necessarily a scam, where academics deliberately exclude a poorly performed study that flatters homeopathy, or any other kind of paper, from a systematic review of the literature, and it’s not through a personal or moral bias: it’s for the simple reason that if a study is no good, if it is not a “fair test” of the treatments, then it might give unreliable results, and so it should be regarded with great caution.

There is a moral and financial issue here too: randomizing your patients properly doesn’t cost money. Blinding your patients to whether they had the active treatment or the placebo doesn’t cost money. Overall, doing research robustly and fairly does not necessarily require more money; it simply requires that you think before you start. The only people to blame for the flaws in these studies are the people who performed them. In some cases they will be people who turn their backs on the scientific method as a “flawed paradigm,” and yet it seems their great new paradigm is simply “unfair tests.”

These patterns are reflected throughout the alternative therapy literature. In general, the studies that are flawed tend to be the ones that favor homeopathy, or any other alternative therapy, and the well-performed studies, in which every controllable source of bias and error is excluded, tend to show that the treatments are no better than placebo.

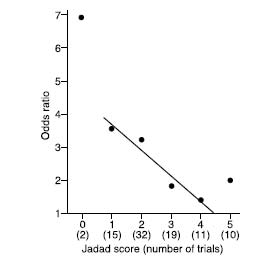

This phenomenon has been carefully studied, and there is an almost linear relationship between the methodological quality of a homeopathy trial and the result it gives. The worse the study—which is to say, the less it is a “fair test”—the more likely it is to find that homeopathy is better than placebo. Academics conventionally measure the quality of a study using standardized tools like the Jadad score, a seven-point tick list that includes things we’ve been talking about, like “Did they describe the method of randomization?” and “Was plenty of numerical information provided?”

This graph, from Ernst’s paper, shows what happens when you plot Jadad score against result in homeopathy trials. Toward the top left, you can see rubbish trials with huge design flaws that triumphantly find that homeopathy is much, much better than placebo. Toward the bottom right, you can see that as the Jadad score tends toward the top mark of 5, as the trials become more of a “fair test,” the line tends toward showing that homeopathy performs no better than placebo. There is, however, a mystery in this graph, an oddity, and the makings of a whodunit. That little dot on the right-hand edge of the graph, representing the ten best-quality trials, with the highest Jadad scores, stands clearly outside the trend of all the others. This is an anomalous finding; suddenly, only at that end of the graph, there are some good-quality trials bucking the trend and showing that homeopathy is better than placebo.

What’s going on there? I can tell you what I think: some of the papers making up that spot are rigged. I don’t know which ones, how it happened, or who did it, in which of the ten papers, but that’s what I think. Academics often have to couch strong criticism in diplomatic language. Here is Professor Ernst, the man who made that graph, discussing the eyebrow-raising outlier. You might decode his political diplomacy and conclude that he thinks there’s been a fix too.

There may be several hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. Scientists who insist that homeopathic remedies are in every way identical to placebos might favor the following. The correlation provided by the four data points (Jadad score 1–4) roughly reflects the truth. Extrapolation of this correlation would lead them to expect that those trials with the least room for bias (Jadad score = 5) show homeopathic remedies are pure placebos. The fact, however, that the average result of the 10 trials scoring 5 points on the Jadad score contradicts this notion, is consistent with the hypothesis that some (by no means all) methodologically astute and highly convinced homeopaths have published results that look convincing but are, in fact, not credible.

But this is a curiosity and an aside. In the bigger picture it doesn’t matter, because overall, even including these suspicious studies, the meta-analyses still show, overall, that homeopathy is no better than placebo.

Meta-analyses?

Meta-Analysis

This will be our last big idea for a while, and this is one that has saved the lives of more people than you will ever meet. A meta-analysis is a very simple thing to do, in some respects: you just collect all the results from all the trials on a given subject, bung them into one big spreadsheet, and do the math on that, instead of relying on your own gestalt intuition about all the results from each of your little trials. It’s particularly useful when there have been lots of trials, each too small to give a conclusive answer, but all looking at the same topic.

So if there are, say, ten randomized, placebo-controlled trials looking at whether asthma symptoms get better with homeopathy, each of which has a paltry forty patients, you could put them all into one meta-analysis and effectively (in some respects) have a four-hundred-person trial to work with.

In some very famous cases—at least, famous in the world of academic medicine—meta-analyses have shown that a treatment previously believed to be ineffective is in fact rather good, but because the trials that had been done were each too small, individually, to detect the real benefit, nobody had been able to spot it.

As I said, information alone can be lifesaving, and one of the greatest institutional innovations of the past thirty years is undoubtedly the Cochrane Collaboration, an international not-for-profit organization of academics that produces systematic summaries of the research literature on health care research, including meta-analyses.

The logo of the Cochrane Collaboration features a simplified blobbogram, a graph of the results from a landmark meta-analysis that looked at an intervention given to pregnant mothers. When women give birth prematurely, as you might expect, the babies are more likely to suffer and die. Some doctors in New Zealand had the idea that giving a short, cheap course of a steroid might help improve outcomes, and seven trials testing this idea were done between 1972 and 1981. Two of them showed some benefit from the steroids, but the remaining five failed to detect any benefit, and because of this, the idea didn’t catch on.

Eight years later, in 1989, a meta-analysis was done by pooling all this trial data. If you look at the blobbogram in the logo on the previous page, you can see what happened. Each horizontal line represents a single study: if the line is over to the left, it means the steroids were better than placebo, and if it is over to the right, it means the steroids were worse. If the horizontal line for a trial touches the big vertical nil effect line going down the middle, then the trial showed no clear difference either way. One last thing: the longer a horizontal line is, the less certain the outcome of the study was.

Looking at the blobbogram, we can see that there are lots of not-very-certain studies, long horizontal lines, mostly touching the central vertical line of no effect; but they’re all a bit over to the left, so they all seem to suggest that steroids

might

be beneficial, even if each study itself is not statistically significant.

The diamond at the bottom shows the pooled answer: that there is in fact very strong evidence indeed for steroids reducing the risk—by 30 to 50 percent—of babies dying from the complications of immaturity. We should always remember the human cost of these abstract numbers: babies died unnecessarily because they were deprived of this lifesaving treatment for a decade. They died

even when there was enough information available to know what would save them

, because that information had not been synthesized together, and analyzed systematically, in a meta-analysis.

Back to homeopathy (you can see why I find it trivial now). A landmark meta-analysis was published recently in

The Lancet

. It was accompanied by an editorial titled “The End of Homeopathy?” Shang et al. did a very thorough meta-analysis of a vast number of homeopathy trials, and they found, overall, adding them all up, that homeopathy performs no better than placebo.

The homeopaths were up in arms. If you mention this meta-analysis, they will try to tell you that it was a fix. What Shang et al. did, essentially, like all the previous negative meta-analyses of homeopathy, was to exclude the poorer-quality trials from their analysis.

Homeopaths like to pick out the trials that give them the answer that they want to hear and ignore the rest, a practice called cherry-picking. But you can also cherry-pick your favorite meta-analyses or misrepresent them. Shang et al. were only the latest in a long string of meta-analyses to show that homeopathy performs no better than placebo. What is truly amazing to me is that despite the negative results of these meta-analyses, homeopaths have continued—right to the top of the profession—to claim that these same meta-analyses

support

the use of homeopathy. They do this by quoting only the result for

all

trials included in each meta-analysis. This figure includes all of the poorer-quality trials. The most reliable figure, you now know, is for the restricted pool of the most “fair tests,” and when you look at those, homeopathy performs no better than placebo. If this fascinates you (and I would be very surprised), then I am currently producing a summary with some colleagues, and you will soon be able to find it online at badscience.net, in all its glorious detail, explaining the results of the various meta-analyses performed on homeopathy.

Clinicians, pundits, and researchers all like to say things like “There is a need for more research,” because it sounds forward-thinking and open-minded. In fact, that’s not always the case, and it’s a little-known fact that this very phrase has been effectively banned from the

British Medical Journal

for many years, on the ground that it adds nothing; you may say what research is missing, on whom, how, measuring what, and why you want to do it, but the hand-waving, superficially open-minded call for “more research” is meaningless and unhelpful.

There have been more than a hundred randomized placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy, and the time has come to stop. Homeopathy pills work no better than placebo pills; we know that much. But there is room for more interesting research. People do experience that homeopathy is positive for them, but the action is likely to be in the whole process of going to see a homeopath, of being listened to, having some kind of explanation for your symptoms, and all the other collateral benefits of old-fashioned, paternalistic, reassuring medicine. (Oh, and regression to the mean.)

So we should measure that, and here is the final superb lesson in evidence-based medicine that homeopathy can teach us: sometimes you need to be imaginative about what kinds of research you do, compromise, and be driven by the questions that need answering, rather than by the tools available to you.

It is very common for researchers to research the things that interest them, in all areas of medicine, but they can be interested in quite different things from patients. One study actually thought to ask people with osteoarthritis of the knee what kind of research they wanted to be carried out, and the responses were fascinating: they wanted rigorous real-world evaluations of the benefits from physiotherapy and surgery, from educational and coping strategy interventions, and other pragmatic things. They didn’t want yet another trial comparing one pill with another or with placebo.

In the case of homeopathy, similarly, homeopaths want to believe that the power is in the pill, rather than in the whole process of going to visit a homeopath, having a chat, and so on. It is crucially important to their professional identity. But I believe that going to see a homeopath is probably a helpful intervention, in some cases, for some people, even if the pills are just placebos. I think patients would agree, and I think it would be an interesting thing to measure. It would be easy, and you would do something called a pragmatic waiting list–controlled trial.