Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (21 page)

But it was Torriente’s hitting on which he built his reputation. Known as a “bad-ball” hitter and nicknamed the “Cuban Strongman” for his broad shoulders, the lefthanded Torriente drove the ball with power to all fields. He holds the record for the highest lifetime batting average in Cuban League play, with a mark of .350, and led that league in every batting category in both 1919 and 1920. He batted over .400 once for the Cuban Stars of the Negro Leagues, and surpassed the .300-mark at least seven other times. Various sources have him hitting somewhere between .333 and .339 over the course of his Negro League career. He won three Negro National League championships as a member of the Chicago American Giants.

Torriente had two things working against him in the analysis of his Hall of Fame credentials. First, his fondness for alcohol and high living in general caused his physical skills to deteriorate rapidly. As a result, Torriente was an exceptional player for a relatively brief amount of time. In addition, the statistics for the first half of his career are extremely limited due to the lack of an organized Negro League at that point. Nevertheless, Torriente’s reputation as arguably the greatest Cuban player in history is difficult to ignore. We will, therefore, assume that his 2006 induction into Cooperstown was a valid one.

Willard Brown was one of the most talented athletes ever to play in the Negro Leagues. He was exceptionally fast in the field, a good baserunner, and an excellent outfielder with a good throwing arm. Brown was most famous, though, for being black baseball’s premier home-run hitter of the 1940s. The free-swinging Brown was a notorious bad-ball hitter who, using a 40-ounce bat, hit with power to all fields. Playing in the western-based Negro American League, Brown won seven home-run crowns during his 13-year career, which was interrupted for two seasons by World War II. More than just a slugger, Brown also captured three batting titles, leading the league with averages of .371 in 1937, .356 in 1938, and .333 in 1941. He played on the great Kansas City Monarch teams that won five NAL pennants between 1937 and 1942, and ended his career with a .355 lifetime batting average and six Negro League All-Star Game appearances.

Unfortunately, Brown failed in his one brief trial period in the major leagues. Signed by St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck during the 1947 campaign, the 36-year-old Brown batted only .179 in 21 games, before being released by St. Louis. Yet, he managed to hit one home run for the Browns, the first ever by a black player in the American League. Many attributed Brown’s lack of success in St. Louis to the fact that he jumped directly from the Negro Leagues to the majors, without the same sort of minor-league adjustment period earlier accorded Jackie Robinson with the Dodgers.

Regardless of Brown’s failure at the major-league level, there can be no questioning his ability. Tommy Lasorda said, “Willard Brown was one of the greatest hitters I ever saw.” The one thing that others often questioned about Brown, though, was his desire. Many observers felt he never fully lived up to his potential since he lacked drive. They viewed him as someone who loved to play in front of large crowds, but who was also lazy, stubborn, and lackadaisical at times.

Speaking of Brown, one former Negro League player, Quincy Trouppe, said, “He could have been a great ball player. He could hit the long ball, but he was so doggone triflin’! He would walk to the outfield...sometimes causing the pitcher to wait to throw the first pitch. He could hit the ball to rightfield, centerfield, leftfield. He was a great hitter.”

But Buck O’Neil, who played with Brown and later managed him, said, “Willard was so talented, he didn’t look as if he was hustling. Willard Brown stole bases standing up; he didn’t slide because he didn’t have to. He could do all the things in baseball— hit, run, field, throw, and hit for power...But Willard was like Hank Aaron—you always thought he could do a little more. Both Brown and Aaron were so talented, they didn’t look as if they were hustling. Everything looked so easy for them.”

Whether or not Willard Brown ever played up to his great ability is subject to conjecture. However, he clearly accomplished enough during his playing career to earn his place in Cooperstown.

Max Carey

The National League’s top centerfielder, leadoff hitter, and base-stealer for much of the second decade of the 20th century, and for part of the third, was the Pittsburgh Pirates Max Carey. From 1911 to 1925, Carey was the Pirates’ regular centerfielder, and in many of those seasons, the best player in the league at that position. He certainly was in 1912, 1913, and from 1922 to 1925. In 1912, he batted .302, scored 114 runs, and stole 45 bases. The following year, Carey batted .277, scored 99 runs, and led the league with 61 stolen bases. From 1922 to 1925, he batted well over .300 three times, scored well over 100 runs each season, and stole no fewer than 46 bases. His finest season came in 1922 when he batted .329, scored a career-high 140 runs, collected 207 hits, stole 51 bases, and established career bests in home runs (10) and runs batted in (70).

During his career, Carey led the league in stolen bases 10 times en route to finishing with 738 steals, a figure good enough to place him in the top 10 all-time. He was also a league-leader in triples twice, and in runs scored once. Carey batted over .300 six times, scored more than 100 runs five times, stole more than 50 bases six times, and was one of the finest defensive centerfielders the game has seen. In fact, during his career, only Tris Speaker was thought to be his superior as a defensive centerfielder.

However, Carey was never considered to be one of the very best players in the game, or even one of the five or six best outfielders. Among centerfielders alone, he was always rated well behind both Speaker and Ty Cobb as an all-around player, and was thought to be more on a level with the Cincinnati Reds’ Edd Roush, a borderline Hall of Famer, at best. Although he did spend a large portion of his career playing in the Deadball era, Carey’s lifetime batting average of .285 is not particularly impressive.

Nevertheless, if Carey’s greatest strengths are emphasized, he becomes a viable Hall of Fame candidate. He was the National League’s top base-stealer of his time, only slightly less prolific in that area than Ty Cobb. He was an outstanding leadoff hitter, tallying 1,545 runs and collecting 2,665 hits during his career, as well as finishing with a solid .361 on-base percentage. In addition, Carey is considered by most baseball historians to be among the finest defensive centerfielders in baseball history. All things considered, Carey was a borderline Hall of Famer. Though not a truly great player, he excelled in enough areas of the game to have his 1961 election by the Veterans Committee viewed with only minor skepticism.

Kirby Puckett

Kirby Puckett’s election to the Hall of Fame by the BBWAA in 2001, in his first year of eligibility, symbolized the degree to which the Hall’s standards have dropped over the years. It isn’t that Puckett wasn’t a fine player whose career numbers did not merit a great deal of consideration by the voters. His selection was not a particularly bad one. However, Puckett’s election in his very first year of eligibility can be looked upon as a slight to the earlier greats who failed to gain admittance to Cooperstown the first time their names appeared on the ballot. There is little doubt that Puckett’s tremendous popularity with both the media and the fans facilitated his speedy induction. But the fact remains that he had only three truly “dominant” seasons during a career that was ended prematurely by an eye injury. Let’s take a closer look at his qualifications.

Puckett played 12 seasons for the Minnesota Twins, from 1984 to 1995. He finished with an outstanding .318 batting average and 2,304 hits. He batted over .300 eight times, topping the .330-mark on three occasions. Puckett hit more than 20 homers six times, drove in over 100 runs three times, scored more than 100 runs three times, and collected more than 200 hits five times. He won a batting title, and also led the league in hits four times. He was selected to the American League All-Star Team nine times, and he finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting six times, making it into the top five on three occasions.

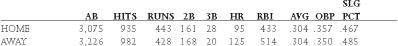

However, it should be noted that Puckett played during a relatively good era for hitters, in one of the best-hitting ballparks in the major leagues—Minnesota’s Metrodome. It’s artificial surface and relatively shallow outfield fences greatly inflated Puckett’s numbers, padding his batting average, home run, and RBI totals considerably. To illustrate the degree to which the Metrodome affected Puckett’s offensive statistics, here are the numbers he compiled during his career playing at home and on the road:

Clearly, Puckett was a much better player in Minnesota than he was everywhere else. In virtually the same number of at-bats, he finished well ahead in every offensive category playing at home. In particular, note the huge discrepancies in batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, hits, and runs scored. It would, therefore, not be totally unreasonable to conclude that Puckett was a somewhat overrated player.

Using our Hall of Fame criteria, Puckett was never considered to be either the best player in baseball or the best player in his league. He was, however, considered to be among the five or six best players in the game, and the best centerfielder in baseball, in at least a few seasons. In 1988, 1992, and 1994 he was clearly among the game’s best players, and arguably the best centerfielder in the majors. In the first of those seasons, he hit 24 home runs, knocked in 121 runs, batted .356, scored 109 runs, and collected 234 hits. In 1992, he hit 19 homers, drove in 110 runs, batted .329, scored 104 runs, and totaled 210 hits. In 1994, he finished with 20 homers and 112 RBIs, and batted .317. Puckett also had outstanding seasons in 1986, 1987, 1989, and 1991 that made him the best centerfielder in the American League. We saw earlier that he fared well in the MVP voting, and that he was selected to nine All-Star teams. He was also a league-leader in a major offensive category five times, and he was a major contributor to his team’s success, helping Minnesota to two world championships. So, overall, Puckett does rather well in these areas.

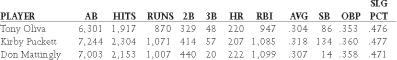

Consider, however, that his career statistics are actually quite comparable to those compiled by two other players who were even more dominant in their primes, yet who are not in the Hall of Fame. Those two players were Tony Oliva and Don Mattingly.

Let’s take a look at the numbers of all three players:

Mattingly’s numbers are amazingly similar, and he was a contemporary of Puckett. In addition, he won an MVP Award (something Puckett never did), he was considered to be the best player in baseball at his position for at least four years (1984-1987), and he was considered by many to be the best player in the game from 1985 to 1987.

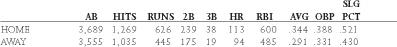

Oliva, in almost 1,000 fewer at-bats, put up numbers that were quite comparable to those of Puckett. Furthermore, he played during the 1960s and 1970s, a period during which it was far more difficult to compile outstanding offensive numbers. Oliva also played for the same team as Puckett, but in a different ballpark that was far less advantageous to hitters. He was considered to be one of the very best players in the American League, and he was arguably its finest hitter for much of his career. Indeed, a look at the batting statistics compiled by Oliva during his career while playing at home, and on the road, indicate just how good a hitter he was: