Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (27 page)

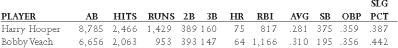

Veach, who played simultaneously with Hooper from 1912 to 1925, had his finest seasons playing alongside Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford, and, later, Harry Heilmann, in the Detroit Tiger outfield. In approximately 2,000 fewer at-bats than Hooper, he hit almost as many home runs, knocked in 350 more runs, hit 30 points higher, and finished with almost the same number of doubles and triples. The only real edge that Hooper had was in runs scored and stolen bases. In addition, Veach knocked in more than 100 runs six times (something Hooper never even came close to doing even once), batted over .300 nine times, reaching a career-best of .355 for the Tigers in 1919, collected more than 200 hits twice, stole more than 20 bases five times, and finished in double-digits in triples ten times. He was a more productive and dangerous hitter than Hooper, and a better ballplayer. Yet he received practically no support in the Hall of Fame voting. Should Veach have been elected? The answer is no. His numbers just were not outstanding enough. But he was certainly more deserving than Hooper, who never should have been voted in.

SHOELESS JOE JACKSON AND PETE ROSE

SHOELESS JOE JACKSON AND PETE ROSE

There is no doubt, based strictly on their playing ability, that both Shoeless Joe Jackson and Pete Rose belong in the Hall of Fame. Among non-pitchers, Jackson was one of the greatest players of the Deadball Era, surpassed only by Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, and, perhaps, Tris Speaker. His lifetime batting average of .356 is the third highest ever (behind only Cobb and Rogers Hornsby), he is the only player in baseball history to hit .400 in his first full season in the major leagues, and he was a terrific outfielder and baserunner.

Pete Rose, while not as talented as Jackson, got the most out of his ability and parlayed a 24-year career in the majors into becoming the all-time leader in base hits, games played, and at-bats. He is also second in doubles, fifth in runs scored, and sixth in total bases. He was an All-Star at five different positions, and he won a Most Valuable Player Award.

The thing that is keeping both men out of the Hall of Fame is the issue of morality, since both were found guilty of breaking the rules of baseball by being involved with gambling on the sport, albeit on totally different levels. Rose was banned from baseball, for life, on August 23, 1989, at the conclusion of a six-month investigation into allegations that he bet on baseball. Jackson and eight other players were banned, for life, by then-Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis in June of 1921 for doing the unthinkable—throwing the 1919 World Series. Perhaps a review of the circumstances surrounding the Black Sox scandal of 1919 is in order.

In September of 1920, a Chicago grand jury convened to investigate charges about the 1919 World Series between the Chicago White Sox and Cincinnati Reds. Meanwhile, an article appeared on September 27, 1920, in the

Philadelphia North

American

in which local gambler Bill Maharg described how White Sox pitcher Ed Cicotte volunteered to fix the Series; how Maharg and his partner, former major leaguer Billy Burns, promised to pay $100,000 to eight White Sox players; how the gamblers double-crossed the players by paying them only $10,000 at first; how the players double-crossed the gamblers by winning a game they were supposed to lose; and how Burns and Maharg got double-crossed by a rival fixer, New York gambler Abe Attell, who

also

was bribing the players. The following day, Cicotte agreed to testify to the grand jury and named the players who, from that point on, became known as the

Black Sox

. The eight players named were Cicotte, fellow-pitcher Claude “Lefty” Williams, outfielders “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and Oscar “Happy” Felsch, infielders Buck Weaver (who had “guilty knowledge” of the fix, but refused to take part in it), Swede Risberg, Chick Gandil, and utility player Fred McMullin.

In grand jury testimony, Gandil emerged as the ringleader, pocketing $35,000. Cicotte received $10,000, and Jackson was paid $5,000 (he was earning about $6,000 a year from tightfisted White Sox owner Charles Comiskey). Arnold Rothstein, the notorious gangster, reputedly masterminded the fix, although his role was never legally proven and he was never charged with a crime. However, following the mysterious disappearance of their confessions, and other legal machinations, the eight Black Sox won acquittal during their June, 1921 conspiracy trial. But the newly appointed baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, in an extraordinarily bold move aimed at restoring public confidence in the game, suspended all eight players for life.

From all this, it becomes quite clear that Joe Jackson was no saint. For that matter, neither was Pete Rose. Throughout his career, and subsequent to his playing days as well, Rose often displayed his egocentricity, arrogance, and self-absorption. Away from the field, he cheated on his wife openly, causing her great public embarrassment and humiliation. Neither man was a role model for youngsters, or the type of person anyone should try to emulate.

However, being a nice guy has never been a prerequisite for entering the Hall of Fame, since it already has several members who were of rather questionable character. The most obvious example would be Ty Cobb, who was the most hated man in baseball during his playing days. He was ruthless, argumentative, vindictive, and violent. During his career, Cobb engaged in drawn-out, knockdown fights with umpires, teammates, opposing players, and fans alike.

Perhaps the most famous of these incidents occurred on May 15, 1912, at Hilltop Park in Manhattan, during a game between Cobb’s Tigers and the New York Highlanders. A heckling fan had been shouting insults at Cobb from the stands all game. However, when he yelled at Cobb that he was a “half-nigger” (considered, in those days, to be the ultimate insult given to a white man), Cobb vaulted the fence and began stomping and kicking the fan with his spikes. When fans began yelling that the man was helpless because he had no hands, Cobb replied, “I don’t care if he doesn’t have any feet,” and kept kicking him until park police eventually pulled him away. When he was informed of the incident, American League President Ban Johnson suspended Cobb indefinitely from organized ball. However, the suspension was lifted when Cobb’s Tiger teammates went on strike to show their support for him, since, at that time, being called a “half-nigger” was considered to be more than any white man could reasonably be expected to take. In the end, Cobb was reinstated after paying just a $50 fine.

As a result of his involvement in incidences such as this, in spite of the fact that he was one of the greatest players who ever lived, Cobb was an embarrassment to the game in many ways. Yet, he was one of the original five members elected to the Hall of Fame in 1936, receiving more votes than any other player. It is, therefore, safe to assume that the writers who voted for him did not place too much importance on “character,” “integrity,” and “sportsmanship” when making their selections.

While Cobb is the most flagrant example, there are many other people in the Hall of Fame who were not chosen based on the quality of their character. In an earlier chapter, it was mentioned that Cap Anson threatened to organize a players’ strike to bar black players from competing in the major leagues prior to a game in 1885. His protest was upheld and it eventually led to the gentlemen’s agreement among owners that prevented blacks from playing in the majors, no matter how good they were, until 1947.

Babe Ruth, as a member of the Boston Red Sox in 1917, attacked umpire Brick Owens. He also went into the stands one time with a bat to chase a heckler. In 1922 alone, he was suspended five times, usually for swearing at umpires. Of course, this was nothing compared to his actions off the field. A legendary philanderer, Ruth once bragged that he had slept with every girl in a St. Louis whorehouse, and, even when his first wife Helen accompanied him on road trips, teammates facilitated his romantic trysts by making their rooms available to him for his liaisons. Ruth also had huge appetites for food and beverage, and was a known drunkard. Mickey Mantle was another who was anything but a model citizen, and drinking problems also came to be associated with players such as Hack Wilson, Chuck Klein, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Paul Waner.

Another player who was elected to the Hall of Fame despite his off-the-field transgressions was pitcher Ferguson Jenkins. The former Chicago Cub, then pitching for the Texas Rangers, was arrested at the Toronto airport on August 25, 1980 for possession of two ounces of marijuana, two grams of hashish, and four grams of cocaine. He was later found guilty of cocaine possession.

But neither Shoeless Joe Jackson nor Pete Rose has been banned from the game because they were bad people, or because of anything they did in their personal lives. They were banned from baseball because they broke the rules of the game and threatened its integrity. Rose broke the rule against gambling, and Jackson took a bribe to throw the World Series. A look back into baseball history reveals, however, that certain Hall of Fame players were, at one time or another, involved in some rather suspicious activities that threatened the integrity of the game.

There was a reported attempt to bribe players in the first two World Series, in 1903 and 1905. In the 1905 Series, Philadelphia A’s pitcher Rube Waddell did not play due to an injury, while he had allegedly received a $17,000 offer not to play. Yet any reports regarding the offer were never fully investigated and Waddell was eventually voted into Cooperstown.

Although there were many reports of attempted fixes during the first two decades of the 20th century, under Judge Landis’ stern tutelage, baseball became far less tolerant of gamblers than it had been in the past. Still, stories of corruption continued to surface. In 1926, player-managers Ty Cobb of the Tigers and Tris Speaker of the Indians both resigned under a cloud of suspicion. The public later learned that ex-pitcher Dutch Leonard alleged that they had conspired to fix the last game of the 1919 season so that Detroit could win third-place money, and that Smoky Joe Wood allegedly placed bets for Cobb and Speaker. In 1927,

“

Black Sox

”

Swede Risberg publicly charged that some 50 players had known of a four-game series in 1917 that the Tigers threw to the White Sox. Yet, both Cobb and Speaker went unscathed because Landis felt that they were too big to be prosecuted. So much for the integrity of Judge Landis.

While we are on the subject of Landis, who was elected to the Hall of Fame by his former cronies in 1944, it might be worthwhile to take a closer look at his character and integrity, or lack thereof.

Throughout his term of office, Kenesaw Mountain Landis presided over the game of baseball in much the same manner that a despot rules a nation, often coming across as pompous, arrogant, and self-righteous. He always enjoyed accepting credit for “saving” the game of baseball with his banishment of the eight

“

Black Sox

”

players who threw the World Series. Meanwhile, he did more to hurt the game than anything else. He showed preferential treatment to those men who helped him get elected to office. Prime examples of this were his handling of the 1919

“

Black Sox

”

scandal, and his subsequent dealings with White Sox owner Charles Comiskey.

Comiskey was notoriously cheap and, as a result, was universally disliked by everyone on the White Sox. In fact, even prior to the 1919 World Series, the White Sox players were nicknamed the

“

Black Sox

.”

The story goes that, one year, Comiskey refused to pay for the laundering of his players’ uniforms, so they played with dirty uniforms. Finally, Comiskey relented and agreed to foot the bill. Then, at the end of the season, he took it out of their World Series paychecks. Such parsimoniousness, and the resentment it caused among his players, as much as anything, is what resulted in the throwing of the 1919 Series.

It later surfaced that, shortly after the Series ended, Joe Jackson wrote a letter to Comiskey stating that the Series outcome was questionable and he volunteered to meet with the owner to provide details. This was actually almost a year before the scandal broke. But Comiskey—said to be concerned about the effect of such revelations on attendance and profits, not to mention his equity in the franchise—never followed up on Jackson’s offer. Yet, when Judge Landis announced his edict, banishing the eight players for life, Comiskey went unscathed. In fact, he was eventually elected to the Hall of Fame by the Old-Timers Committee, of which Landis was a member.

Of even greater significance, though, is the fact that it was Landis, more than anyone else, who fostered the notion that black players should not be allowed in the major leagues. While this was never officially announced by anyone, or written anywhere into the rules, it was an understanding amongst the owners, enforced by Landis. Not until he passed away in 1944, and “Happy” Chandler took over as Commissioner, were the gates opened for everyone to participate in major league baseball.

The point here is that baseball has always been an hypocrisy, and, for years, Landis was a symbol of that hypocrisy. Anything that happened during his term of office, any decisions he handed down, and any rules he made should be taken lightly. How could the rulings of a man who excluded such a large segment of the population from the national pastime be taken seriously? How could the rules created even after his term ended be taken seriously when the powers that be have never fully enforced them? Just look at former pitcher Steve Howe. After six violations of baseball’s anti-drug policy, which included a year-long suspension in 1984, Howe was suspended “for life” in June of 1992 by then-commissioner Fay Vincent. However, he was eventually reinstated, only to suffer a seventh suspension.

Therefore, those who say that Shoeless Joe Jackson and Pete Rose should not be allowed to enter the Hall of Fame because they were banished for life for “breaking the rules” of the game should take a long look back into baseball history. Doing so might cause them to reevaluate their position. Jackson and Rose should be no more excluded than men such as Cobb, Speaker, Waddell, Comiskey, and Landis. Their names should be included on the eligible list, and the current members of the Hall of Fame should be the ones to determine their fate. Some of them have already gone on record as saying that they do not wish to have the names of Jackson and Rose intermingled with theirs. They certainly have a right to feel that way, but that should be

their

decision to make. It should not be made for them by other individuals who, over the years, have contributed to the hypocrisy that has come to symbolize major league baseball. Jackson, who was banished from the game “for life,” has been dead for almost 50 years. Rose should never be permitted to either manage or coach again, but his name should appear on the eligible list as well.