Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (26 page)

Hall-of-Famer Johnny Mize once said that Dihigo was the best player he ever saw and recalled that when the two men were teammates in the Dominican Republic, opponents sometimes intentionally walked Dihigo to pitch to him.

All evidence seems to indicate that the Negro Leagues Committee did a good job when it elected Dihigo to the Hall of Fame in 1977.

Enos Slaughter

Enos Slaughter is a prime example of the type of player who has caused disagreement over the years between those who feel that only the great players should be elected to the Hall of Fame, and those who are less stringent in their approach to the elections.

Slaughter played 19 years for the St. Louis Cardinals, Kansas City Athletics, New York Yankees, and Milwaukee Braves. His peak years were spent with the Cardinals, from 1938 to 1953, with three years of playing time lost due to his stint in the military. During his years in St. Louis, Slaughter never hit less than .276, and he topped the .300-mark eight times. Although he never hit more than 18 home runs in any season, Slaughter knocked in and scored more than 100 runs three times each, finished in double-digits in triples seven times, and compiled as many as 52 doubles one year. His most productive season was 1946, when he helped lead the Cardinals to the world championship by hitting 18 home runs, knocking in a league-leading 130 runs, batting .300, and scoring 100 runs. He also had outstanding seasons in both 1942 and 1949. In his last year of play prior to joining the war effort, Slaughter hit 13 home runs, drove in 98 runs, scored 100 others, and batted .318. In 1949, he hit 13 homers, knocked in 96 runs, and batted .336.

In his years with St. Louis, Slaughter led the league in batting once, runs batted in once, triples twice, and doubles and hits once each. He was selected to the All-Star Team ten times, and finished in the top 10 in the league MVP voting five times, making it into the top five on three separate occasions.

However, while Slaughter was an extremely consistent player who had many good years, he was never able to put together that one

great

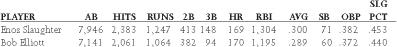

, truly dominant Hall-of-Fame-type season. In his prime, he was not as good as several other outfielders who are not in the Hall of Fame. Players such as Bob Johnson, Bob Elliott, and Tony Oliva were all, at their peaks, superior players to Slaughter. They just didn’t hang around as long as he did. Elliott, in particular, is a good example because he was a National League contemporary of Slaughter, playing for the Pirates and Braves, among others, from 1939 to 1953. A look at the career numbers of both players indicates that they were actually quite comparable:

Elliott, who played both third base and the outfield during his career, hit as many home runs as Slaughter and knocked in only 100 fewer runs in 800 fewer at-bats. He was also quite comparable in most other offensive categories. Elliott hit more than 20 homers three times (something Slaughter never did), knocked in over 100 runs six times, and was named the National League’s MVP in 1947 when, playing for the Braves, he hit 22 homers, knocked in 113 runs, and batted .317. Yet, Elliott received only minimal support during his eligibility period.

Using our other Hall of Fame criteria, Slaughter was never considered to be even among the 10 best players in the game, much less the top five, and, with the possible exception of 1946, was never even among the five best players in his own league. He was, however, the best rightfielder in baseball in at least a few seasons. He certainly was in 1941, 1942, 1946, 1948, and 1949, all seasons in which he batted over .300 and, with the exception of 1941, knocked in over 90 runs. In addition, Slaughter’s offensive productivity and hustling style of play—epitomized by his “maddash” around the bases to score the winning run in the 1946 World Series against the Boston Red Sox—contributed greatly to his teams’ success. He played on five pennant-winners and four world champions in St. Louis and New York.

The inevitable question that follows: was the Veterans Committee’s 1985 selection of Slaughter justified? Once again, the answer lies in the manner in which one chooses to evaluate the credentials of potential Hall of Fame candidates. Slaughter was clearly not a great player. In fact, he was a very good one in only about six or seven seasons. He was, however, a good player for a very long time. The feeling here is that Slaughter should be viewed as a borderline Hall of Famer, at best. While he was far from the worst selection ever made by the Veterans Committee, he is someone who, in all probability, should never have been elected.

Elmer Flick

The man who replaced Sam Thompson in the Philadelphia Phillies’ outfield in 1898 was Elmer Flick. Flick’s 13-year major league career included four seasons with the Phillies and nine with the American League’s Cleveland Indians. Over his 13 seasons, Flick batted over .300 eight times, scored more than 100 runs twice, collected more than 200 hits and knocked in more than 100 runs once each, stole more than 30 bases seven times, and finished in double-digits in triples ten times. He led his league in runs batted in, batting average, and runs scored once each, and triples three times. Flick finished his career with a .313 batting average, a .389 on-base percentage, 164 triples, and 330 stolen bases.

However, Flick was never considered to be the best rightfielder in his league, being ranked behind both Willie Keeler and Sam Crawford in virtually every season. In addition, his career was a relatively short one, his 5,600 at-bats permitting him to accumulate only 756 runs batted in, 948 runs scored, and 1,752 hits—paltry numbers by Hall of Fame standards. Flick was a good player, but he just didn’t do enough to merit his 1963 selection by the Veterans Committee, which is one that never should have been made.

Ross Youngs

The career of New York Giants outfielder Ross Youngs was an abbreviated one that was halted by a fatal illness he incurred during the 1926 season. Prior to that, Youngs was one of the better players in the National League, hitting over .300 in nine of his ten big-league seasons. His finest years came from 1920 to 1924. In those five seasons, he never batted below .327, surpassing the .350-mark twice. He also scored more than 100 runs three times, collected more than 200 hits twice, and finished in double-digits in triples in each of those years. From 1920 to 1923, Youngs was the National League’s best rightfielder.

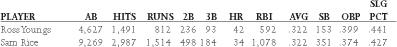

However, hitting mostly during the 1920s, Youngs’ batting statistics were somewhat inflated by the offensive explosion that took place at the time. He never came close to leading the league in hitting, finishing well behind Rogers Hornsby in the batting race in each season, from 1920 to 1925. He led the National League in runs scored and doubles once each, but had little power, hitting as many as 10 home runs only once, and knocking in 100 runs only one time. In fact, in no other season did Youngs drive in as many as 90 runs. He was never considered to be among the best players in the game, or even in his own league. A look at his career numbers, next to those of Sam Rice, is quite revealing:

The two players were virtually equal in productivity throughout their careers. In twice the number of at-bats, Rice finished with twice as many runs batted in, runs scored, hits, triples, doubles, and stolen bases. While Youngs hit more home runs and finished with slightly higher on-base and slugging percentages, the two men finished with the exact same batting average. Yet, in spite of their comparable level of offensive productivity, Rice played twice as long as Youngs and, therefore, compiled far more impressive numbers during his career. Youngs’ career numbers suffer greatly when compared to those posted by Rice and are clearly not Hall of Fame caliber. In short, Youngs was a good player, but his selection by the Veterans Committee in 1972, due largely to the influence of his former teammate, Committee member Frankie Frisch, was a big mistake.

Tommy McCarthy

The 13-year career of Tommy McCarthy included stints with the Boston Braves, Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, and Brooklyn Dodgers. After struggling in his first few seasons, McCarthy came into his own in 1888, when he stole 93 bases and scored 100 runs for the first of seven consecutive seasons. Over that seven-year period, he also knocked in over 100 runs twice, batted over .300 four times, and stole more than 40 bases six times.

McCarthy’s finest years came in 1890, 1893, and 1894. Playing for the Cardinals in 1890, he batted .350, stole 83 bases, and scored 137 runs. With the Braves in 1893, he hit .346, knocked in 111 runs, and scored 107 others. The following season, he established career highs in home runs (13) and runs batted in (126), while batting .349 and scoring 118 runs.

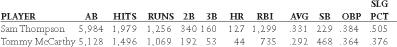

However, McCarthy led his league only once in any major offensive category (stolen bases), and was never considered to be an exceptional player, or even the best at his own position. Playing rightfield at the same time as Sam Thompson, McCarthy was rated well behind the 19th century slugger throughout his career. A look at the numbers of both players illustrates the disparity in their skill levels:

In approximately 800 fewer at-bats, the only edge that McCarthy had was in stolen bases. In all other categories, there really is no comparison. Thompson was a far-superior player to McCarthy, who was a good player for seven years, and a very good one for only two or three. Those few good years should not have been enough to get McCarthy elected to the Hall of Fame. His selection by the Veterans Committee in 1946, 28 years before Thompson’s induction in 1974, is indefensible and another indication of how uninformed the Committee members were in the early years of the balloting.

Harry Hooper

Another selection by the Veterans Committee that is difficult to fathom is that of Harry Hooper, who was elected in 1971. Hooper’s major league career lasted 17 seasons, 12 with the Boston Red Sox and five with the Chicago White Sox. With Boston from 1909 to 1920, Hooper was fortunate enough to play alongside the great Tris Speaker in the Red Sox outfield for seven seasons, and, also, with Babe Ruth for six. As a result, he played on several pennant-winning teams and three world champions.

However, just how much Hooper contributed to the success of those teams is somewhat debatable. In his 12 seasons in Boston, he stole more than 20 bases nine times, scored more than 90 runs four times, and finished in double-digits in triples nine times. However, he batted .300 only twice, hitting less than .270 six times, scored 100 runs only once, never knocked in more than 53 runs, and never finished with more than 169 hits. During his entire career, Hooper batted over .300 only five times, scored more than 100 runs only three times, never knocked in more than 80 runs, and never finished with more than 183 hits. He never led the American League in any offensive category and was never considered to be among even the ten best players in the league. In fact, he was never rated any higher than third among rightfielders alone. Throughout his career, he was ranked well behind the likes of Shoeless Joe Jackson and Sam Crawford, and, later, Babe Ruth, Harry Heilmann, and Sam Rice. A look at his career numbers, along with those of Bobby Veach, causes one to wonder what the Veterans Committee was thinking when it selected him: