Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (43 page)

Omar Vizquel

Had he come along 15 or 20 years earlier, in all likelihood Omar Vizquel would have been considered the premier shortstop of his time and a favorite to enter the Hall of Fame when his playing days were over. However, it was Vizquel’s misfortune to enter the major leagues in 1989, at a time when two of the greatest shortstops in the history of the game, Cal Ripken Jr. and Ozzie Smith, were still in their prime. Vizquel spent his first five years in Seattle being largely overlooked in favor of both Ripken and Smith as the careers of the two men began to wind down. Later, after joining the Cleveland Indians in 1994, Vizquel spent most of his best years coming up short in comparisons to Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, and Nomar Garciaparra, all of whom were considerably larger than the 5'9", 165-pound Venezuelan, and, therefore, possessed much more power at the plate. Thus, Vizquel has spent virtually his entire career being compared to some of the most talented men ever to play the position of shortstop.

Yet, through it all, Vizquel has remained the finest defensive shortstop in the game, and, quite possibly, the best in baseball history, aside from Ozzie Smith. From 1993 to 2001, Vizquel won nine consecutive Gold Glove Awards, and he captured two more after joining the San Francisco Giants in 2005. Vizquel’s career .984 fielding percentage is actually considerably better than Smith’s mark of .978. In 2000, he set a major league record for shortstops by committing only three errors in 647 total chances all year. In three full seasons between 2000 and 2002, he committed a total of just 17 errors.

Vizquel is a competent offensive player as well. His career batting average is .273, and he has batted over .290 five times. He has also scored more than 100 runs twice and stolen more than 30 bases four times. Vizquel had his finest season for the Indians in 1999, when he compiled a batting average of .333, with 112 runs scored, 191 hits, 36 doubles, and 42 stolen bases.

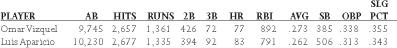

Vizquel’s offensive numbers actually compare quite favorably to those posted by several other Hall of Fame shortstops. Let’s look at his statistics alongside those of Luis Aparicio, another player who was known more for his great glove work than he was for his hitting:

The two men are extremely close in most statistical categories, with Aparicio’s only major advantage being his stolen base total. Vizquel, though, has driven in more runs in fewer at-bats, and has significantly higher on-base and slugging percentages. Certainly, it should be noted that Aparicio played during more of a pitcher’s era. But, offensively, the difference between the two is negligible. And, although Aparicio was considered to be the finest defensive shortstop of his time, he certainly was no better than Vizquel. The biggest difference between the two is that, due to the greater level of competition that Vizquel has faced during his career, Aparicio received more recognition during his playing days for being among the best shortstops in baseball.

As a result of his bad timing, Vizquel has never been regarded as the best shortstop in his league, or even as one of the two or three best. He has been selected to only three All-Star teams, has never finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting, and has never come close to leading the league in any offensive category.

Omar Vizquel has been a fine player throughout his career. In fact, he is clearly better than at least three or four shortstops currently in the Hall of Fame. But, due to the era in which he has competed, and the fact that he has never been regarded as one of the very best shortstops in baseball, Vizquel is not likely to ever receive the support he will need to gain admittance to Cooperstown—something he probably doesn’t quite deserve anyway.

Curt Schilling

Most people probably tend to think of Curt Schilling as a certain Hall of Famer. After all, from 2001 to 2004, he was one of baseball’s most dominant pitchers, and, even before that, he had some truly outstanding seasons. However, the feeling here is that there is a need to take a closer look at Schilling’s career before a plaque is constructed for him at Cooperstown.

In his first eight full seasons in the major leagues, as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies, Schilling was a good pitcher who had the misfortune of playing on predominantly poor teams. He was actually a

very

good pitcher in five of those years. In 1992, he finished only 14-11 but compiled an outstanding 2.35 earned run average. When the Phillies won the pennant the following year, his record improved to 16-7, but his ERA slipped to 4.02. Schilling was also very solid from 1997 to 1999, winning 47 games for weak Phillies teams those years, and striking out more than 300 batters twice. He had perhaps his finest season for the Phillies in 1997, compiling a record of 17-11, with a 2.97 ERA and a league-leading 319 strikeouts. Schilling was a fine pitcher in his years in Philadelphia, but, with the exception of one or two seasons, would have had a difficult time making anyone’s list of baseball’s top ten hurlers.

However, in 2001, as a member of the Arizona Diamondbacks, Schilling took his game to the next level. Experiencing something of a renaissance in Arizona, he became, along with teammate Randy Johnson, baseball’s most dominant pitcher. That year, he finished 22-6, with a 2.98 ERA and 293 strikeouts, and was practically unhittable during the postseason. The following year, he finished 23-7, with a 3.23 ERA and 316 strikeouts. At the end of both seasons, he was named

The Sporting News

Pitcher of the Year. For those two seasons, Schilling was a truly great pitcher, one of the best in the game in quite some time.

Schilling was also extremely effective for the Diamondbacks during the first part of the 2003 campaign, before an injury forced him to miss the final two months of the season.. However, after becoming a free agent during the off-season, Schilling left Arizona to join the Boston Red Sox prior to the start of the 2004 campaign. With the Red Sox, Schilling had another fabulous year, compiling a record of 21-6 and an ERA of 3.26, while striking out 203 batters and leading Boston to its first World Championship in 86 years. Unfortunately, Schilling had a difficult time recovering from a foot injury he sustained late in the 2004 campaign and spent much of 2005 on the disabled list. When he returned to action, he was relatively ineffective much of the time, posting a record of only 8-8, with a 5.59 ERA. Healthy again in 2006, Schilling compiled a record of 15-7 and an ERA of 3.97. Schilling finally began succumbing to Father Time in 2007, when the 40-year-old won only nine of his 24 starts. He then missed the entire 2008 campaign with an injury to his pitching arm that may well bring an end to his major league career.

During his career, Schilling has led his league in wins, strikeouts, and innings pitched twice each, and in complete games four times. He has been selected to the All-Star Team six times, has finished in the top five in the Cy Young voting four times, placing second on three separate occasions, and has finished in the top ten in the MVP voting twice. Schilling has also been a tremendous big-game pitcher. In twelve postseason series, he has compiled a record of 10-2, with an ERA of 2.23, while striking out 120 batters and surrendering only 104 hits in 133 innings of work. In his seven World Series starts, Schilling has gone 3-1 with a 2.06 earned run average.

It would be difficult to disagree too strenuously with anyone who wished to initiate an argument on Schilling’s behalf for his eventual induction into the Hall of Fame. However, it should be pointed out that he has won “only” 216 games—a relatively low number for a Hall of Fame pitcher. In fact, his career won-lost record stands at 216-146, and his earned run average is 3.46. Neither of those figures is particularly overwhelming. Furthermore, while Schilling was a truly great pitcher in 2001, 2002, and 2004, and an exceptional one in 1997, those are the only true Hall-of-Fame type seasons he has ever had. He had three other very good years for the Phillies, and another for the Red Sox, but was not among the very best pitchers in baseball in any of those campaigns. Therefore, even though the dominant image Schilling created of himself in the minds of most people in his years in Arizona, as well as his reputation for being an outstanding postseason performer will undoubtedly earn him a spot in Cooperstown when his playing days are over, the members of the BBWAA should take a step back and carefully consider Schilling’s total body of work before they rush to enter his name on their ballots.

John Smoltz

Another pitcher who is likely to gain admittance to Cooperstown relatively early during his period of eligibility is John Smoltz, who has been one of baseball’s best pitchers for much of the past 20 years.

Although overshadowed somewhat throughout much of his career by fellow Braves pitchers Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine, Smoltz has been one of the National League’s most consistent winners over the last two decades. He has won at least 14 games ten times, leading the league in victories twice, and has also compiled an outstanding 3.26 earned run average. Smoltz has led all N.L. starters in strikeouts and innings pitched two times each, has been named to eight All-Star teams, has won a Cy Young Award, and has finished in the top five in the balloting two other times.

Smoltz had his best year for the Braves in 1996, when he captured N.L. Cy Young honors by finishing with a league-best 24-8 record, 276 strikeouts, and 254 innings pitched, while compiling an excellent 2.94 earned run average. He had another brilliant season in 1998, when he finished 17-3 with a 2.90 ERA despite missing more than a month of the campaign with arm problems. Over the course of his career, Smoltz has also established himself as one of the best big-game pitchers in the sport. In 24 postseason series, he has compiled a record of 15-4 and an exceptional 2.65 earned run average, while allowing only 168 hits in 207 innings of work.

Despite this body of work, the feeling here is that Smoltz should be viewed as a borderline Hall of Famer, rather than as an automatic selection when he eventually becomes eligible for induction. In 15 seasons as a full-time starter, he has won more than 15 games only three times, and, despite spending virtually his entire career with a contending team, he has won “only” 210 games—a relatively modest number for a Hall of Fame pitcher. Furthermore, much of the time, Smoltz was viewed as only the third best starter on his own team, behind both Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine. However, it must also be remembered that Smoltz’s win total is somewhat misleading since he spent four seasons pitching out of the Braves’ bullpen. In his three full years as a reliever, Smoltz saved a total of 144 games and established himself as one of the game’s top closers, before being inserted back into the team’s starting rotation in 2005. In addition, while he usually took a back-seat to Maddux and Glavine during the regular season, Smoltz generally surpassed both men in postseason play. He usually proved to be Atlanta’s best pitcher in the playoffs and World Series.

All things considered, Smoltz’s career won-lost record of 210-147 might make him something of a borderline Hall of Fame candidate. But, should the members of the BBWAA eventually choose to elect him, their decision would not be a bad one at all.

Trevor Hoffman

While others, such as Eric Gagne and Brad Lidge, were exceptional relievers for two or three seasons, the National League’s dominant closer for most of the last 13 years has been Trevor Hoffman. In fact, with the exception of Mariano Rivera, Hoffman has been the best closer in the game since 1996.

Hoffman first assumed that role with the Padres in 1994, compiling 20 saves that year. He has surpassed 30 saves in all but one of the 14 subsequent seasons, topping the 40-mark on nine separate occasions. Hoffman had his finest season in 1998, when he led the league with a career-high 53 saves, while compiling a brilliant 1.48 earned run average, surrendering only 41 hits in 73 innings of work, and striking out 86 batters while walking only 21. He finished second in the Cy Young balloting that year, and, in helping San Diego to the N.L. pennant, also placed seventh in the league MVP voting. Two seasons later, Hoffman walked only 11 batters in 72 innings of work, while striking out 85. After another outstanding season in 2002, in which he saved 38 games in 41 save opportunities, Hoffman missed virtually all of the 2003 campaign due to injury. However, he returned in 2004 to save 41 games, and was extremely effective in each of the next three seasons as well, compiling 43, 46, and 42 saves, respectively. Although age finally began to catch up with Hoffman in 2008, he still managed to save 30 games for the 13th time in his career. In so doing, he increased his major league-leading all-time saves total to 554.

Trevor Hoffman has clearly been one of the finest relief pitchers in baseball history. In addition to leading his league in saves twice, he has finished second five other times. He has also pitched to an excellent 2.78 career ERA, and allowed only 762 hits in 988 innings of work, while striking out 1,055 batters. Hoffman has finished second in the Cy Young balloting twice, and has placed as high as sixth two other times. He also has finished in the top ten in the MVP voting twice and been named to six All-Star teams.