Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (50 page)

Unfortunately, there will undoubtedly be several members of the BBWAA who take a far more liberal approach towards Palmeiro. Many of the writers probably developed an excellent working relationship with him over the years. As a result, they will likely be much more forgiving, and Palmeiro may well end up in Cooperstown. Indeed, in that aforementioned television interview with Fay “Reinstatement” Vincent, the former Commissioner was asked about Palmeiro’s situation, and the possibility of him eventually being elected to Cooperstown. In response, Vincent said that he believed that, in time “…everything would blow over and Raffy would get in.” I suppose one could not have expected anything else from him. One can only hope, though, that not everyone is as forgiving as Vincent, and that the majority of the voters are far more concerned with the integrity of the game.

Ivan Rodriguez

In his book, Jose Canseco claimed that he injected Ivan Rodriguez with steroids when the two men were teammates in Texas. This came as a bit of a surprise to me because, of all the players whose names had previously been linked to the use of performance-enhancing drugs, I thought Rodriguez the least likely candidate to have actually been guilty of using them. Although he was always solidly built, Rodriguez was never overly muscular. And, with the exception of three or four seasons in the middle of his career, he never really compiled any particularly impressive power numbers on offense. I had always taken Rodriguez’s career at face value, never questioning in the least his on-field achievements. And those achievements made him, with the possible exception of Mike Piazza, the best catcher in the game for more than a decade.

Rodriguez first came up with the Texas Rangers in 1991, becoming a regular the following season. Although he hit only 8 home runs, knocked in just 37 runs, and batted only .260 in his first full season, Rodriguez made the All-Star Team and won the first of his ten consecutive Gold Glove Awards. He had solid seasons in each of the next six years, batting over .300 four times, hitting more than 20 homers twice, driving in more than 85 runs twice, scoring more than 100 runs once, and making the All-Star Team each year. His best season was in 1998, when he hit 21 home runs, knocked in 91 runs, batted .321, and scored 88 runs.

Rodriguez dramatically increased his offensive productivity in 1999, when he established new career-highs in home runs (35), runs batted in (113), runs scored (116), and stolen bases (25), batted .332, and was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player. A season-ending injury limited Rodriguez to only 91 games the following year. Yet, he still managed to hit 27 home runs, drive in 83 runs, and bat .347. Although his playing time and offensive productivity were similarly reduced by injuries in each of the next two years, Rodriguez batted over .300 each season, and combined for a total of 44 home runs in only 217 games. In 2003, he signed on as a free agent with the Florida Marlins and ended up leading them to a World Series victory over the New York Yankees. From there, he moved on to Detroit, where he spent four-plus seasons before being traded to the Yankees during the second half of the 2008 campaign.

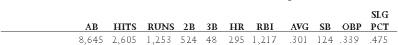

In all, Rodriguez has hit more than 20 homers five times, batted over .300 ten times, and scored more than 100 runs twice. He has been selected to 14 All-Star teams, has won 13 Gold Gloves, and has finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting a total of four times. Here are his career numbers heading into 2009:

Those might appear to be only borderline Hall of Fame type numbers to many, and add to that the fact that Rodriguez has never led his league in any major statistical category, placing in the top five a total of only four times. But consider the following:

1. Rodriguez’s 2,605 hits are the most by any catcher in major league history.

2. Rodriguez’s 1,253 runs scored and 124 stolen bases are the second-highest totals ever compiled by a major league catcher, placing him behind only Carlton Fisk in both categories.

3. Rodriguez’s 524 doubles are the most by any catcher in major league history.

Furthermore, it must be remembered that, as good as Rodriguez was offensively, his greatest strength has always been his defense. Over the years, not very many catchers have even been mentioned in the same breath as Johnny Bench. However, Rodriguez’s fielding has actually been compared quite favorably to Bench’s by many baseball experts. His 13 Gold Glove Awards are a testament to his defensive excellence, and his mere presence behind home plate often intimidates opposing baserunners. Rodriguez’s defensive skills made him easily the American League’s best all-around catcher for most of his career, and, with the possible exception of Mike Piazza, his generation’s best all-around receiver.

Yet, there remains that cloud of suspicion hanging over Rodriguez as a result of the allegations made against him regarding his use of steroids. Did he, in fact, use them, and, if so, to what extent did they enhance his performance? Since Rodriguez never tested positive for steroids, there is no way of knowing for sure. Nevertheless, the feeling here is that the accusations made against him by Jose Canseco in his book were true. Regardless of what one’s personal feelings might be towards Canseco, he seems to have described numerous events quite accurately in his work. And, if he did lie about anything, why haven’t any of the players he lied about sued him for defamation of character?

In addition, Rodriguez’s offensive numbers tend to support Canseco’s claim. After failing to hit more than 21 home runs in any of his first six full seasons, Rodriguez suddenly slugged 35 home runs and drove in a career-high 113 runs in 1999. Over the next three seasons, he combined for 71 home runs in only 310 games. Canseco’s contention is further supported by Rodriguez’s performance since 2005. After the Congressional hearings were held prior to the start of the season, a svelte Rodriguez reported to Detroit Tigers training camp some 25 pounds lighter than he was at the conclusion of 2004. He has totaled only 45 home runs in the four seasons since, covering a total of 509 games. Yet he has remained a solid hitter, posting batting averages of .276, .300, .281, and .276 the last four years.

Thus, the evidence seems to strongly suggest that Rodriguez did indeed use steroids, although he likely used them for only four or five seasons. We will, therefore, work under the assumption that some of his offensive numbers cannot be taken at face value. Still, there is the defensive brilliance Rodriguez displayed behind the plate throughout his career. He was a great receiver from his earliest days in the major leagues, and there is no way of knowing if any performance-enhancing drugs he may have taken further added to his defensive skills. Would they have affected his quickness behind the plate, or his ability to throw runners out on the basepaths? That is open to much conjecture.

Taking all these factors into consideration, the feeling here is that Ivan Rodriguez should be deemed a worthy Hall of Famer when his playing days are over. Although his performance was likely aided a few seasons by the use of steroids, he earlier established himself as one of the two greatest catchers of his generation, and as arguably the finest defensive receiver ever. His 13 Gold Gloves are proof of his defensive brilliance, and he won seven of those prior to 1999, the year his offensive power numbers took a quantum leap. He also appeared in seven All-Star games prior to that, and was already considered to be the American League’s best catcher. The members of the BBWAA should consider those points when Rodriguez eventually becomes eligible for induction.

Roger Clemens

Roger Clemens has often been referred to as the greatest pitcher of his era. Some have even called him the greatest pitcher in baseball history. Clemens’ supporters point to his record seven Cy Young Awards, his 354 career victories, and his 4,672 career strikeouts. They argue that those 354 wins are the ninth highest total ever compiled in the major leagues, and, aside from Warren Spahn’s 363 victories and Greg Maddux’s 355, the most accumulated by any pitcher whose career began after 1920. In addition, Clemens’ 4,672 strikeouts place him third on the all-time list, behind only Nolan Ryan and Randy Johnson.

Clemens was a truly great pitcher for much of his 24-year major league career that began in 1984 with the Boston Red Sox. He had his first great season for Boston in 1986, after becoming a regular member of the team’s starting rotation for the first time at the start of the year. Clemens finished 24-4, with 238 strikeouts and a league-leading 2.48 earned run average to capture both A.L. MVP and Cy Young honors. He was brilliant again the following season, compiling a record of 20-9, with 256 strikeouts and a 2.97 ERA. Clemens was awarded his second straight Cy Young at the end of the season.

Clemens pitched extremely well in both 1988 and 1989, before having arguably his best year for the Red Sox in 1990. Although he finished second in the A.L. Cy Young balloting to Oakland’s Bob Welch, Clemens compiled a record of 21-6, with 209 strikeouts and a league-leading 1.93 earned run average. He captured his third Cy Young Award the following season, finishing 18-10 for Boston and leading the league with 241 strikeouts and a 2.62 ERA. However, after pitching exceptionally well in 1992, Clemens was much less effective the next few seasons, prompting the Red Sox to allow him to leave via free agency prior to the start of the 1997 campaign.

After signing on with the Toronto Blue Jays, Clemens had two of his finest seasons in 1997 and 1998, capturing the pitcher’s version of the triple crown both years. In 1997, he finished 21-7, with 292 strikeouts and a 2.05 ERA. The following year, he went 20-6, with 271 strikeouts and a 2.65 earned run average. Clemens won the Cy Young Award both times. At the end of 1998, he was dealt to the Yankees, for whom he pitched the next five seasons. Although somewhat less effective in his time in New York, Clemens pitched well enough to capture his sixth Cy Young Award in 2001, going 20-3, with 213 strikeouts and a 3.51 ERA. After announcing his retirement at the conclusion of the 2003 season, Clemens decided to pitch for his hometown Houston Astros, with whom he spent the next three years, before rejoining the Yankees for one final season in 2007. In his first year in Houston, Clemens, at the age of 42, won his record seventh Cy Young Award, compiling a record of 18-4, with 218 strikeouts and a 2.98 ERA.

Clemens ended his career with a won-lost record of 354-184 and an outstanding 3.12 earned run average. He led his league in wins four times, earned run average seven times, strikeouts five times, shutouts six times, complete games three times, and innings pitched twice. He won at least 20 games six times and accumulated at least 17 victories six other times. He also struck out more than 200 batters twelve times and compiled an earned run average below 3.00 twelve times, allowing the opposition fewer than two runs per game on two separate occasions. Clemens was a member of 11 All-Star teams and, in addition to winning the Cy Young Award seven times, placed in the top five in the voting three other times. He also finished in the top ten in the MVP balloting six times.

The resume of Roger Clemens is certainly an impressive one, prompting virtually everyone to think of him as a certain first-ballot Hall of Famer upon his retirement. However, Clemens’ situation became far more complex in December of 2007 when his name was included on a list of current and former major league players that allegedly used performance-enhancing drugs during their careers. In an investigation conducted by former United States Senator George Mitchell, Clemens’ former close friend and personal trainer Brian McNamee claimed he injected the pitcher with steroids and provided him with human growth hormones several times while he was a member of the Toronto Blue Jays and New York Yankees. Clemens vehemently denied the accusations, claiming they were lies, strongly defending the integrity of his accomplishments, and crediting much of his success to his intense workout regimen.

But one has to wonder what McNamee had to gain by making false statements about someone who was once so close to him. In addition, McNamee’s testimony was given a great deal of credibility by another player he worked with in New York, Andy Pettitte, who admitted that McNamee’s claim that he provided Pettitte with HGH on at least two separate occasions to help him recuperate from injuries was accurate. Furthermore, Pettitte later testified under oath that Clemens discussed with him the advantages of using HGH when the two were teammates in New York. Pettitte’s testimony was perhaps more damaging to Clemens than McNamee’s since the latter has a somewhat sordid background. Meanwhile, prior to his admitted use of HGH, Pettitte was always viewed as a model citizen.

While Clemens has steadfastly continued to proclaim his innocence, the feeling here is that he is indeed guilty as charged. Although his amazing ability to pitch extremely well into his midforties drew tremendous admiration from baseball enthusiasts everywhere, an examination of the progression of his career would seem to indicate that he received artificial assistance along the way.