Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (49 page)

1989:

33 HR, 95 RBIs, .231 AVG, 74 RUNS

1990:

39 HR, 108 RBIs, .235 AVG, 87 RUNS

1991:

22 HR, 75 RBIs, .201 AVG, 62 RUNS

Those are decent power numbers, but McGwire clearly left a lot to be desired in every other area. Nevertheless, an instant fan favorite after his outstanding rookie season, he was voted onto the All-Star Team by the fans in every one of those years, even though there were far more deserving first basemen each season. In fact, with the possible exception of the 1987 campaign, at no point during that five-year stretch could a legitimate case be made for McGwire being even among the top two first basemen in the American League (at different times, Don Mattingly, Wally Joyner, Fred McGriff, Cecil Fielder, Frank Thomas, and Rafael Palmeiro were all better).

McGwire had his second-best season in 1992, hitting 42 home runs, driving in 104 runs, batting .268, and making his sixth consecutive All-Star team. But, he would have been ranked well behind the even more productive Frank Thomas that year (Thomas knocked in 115 runs and batted .323 for the White Sox). McGwire then suffered through injury-riddled seasons in both 1993 and 1994, appearing in a total of only 74 games.

Thus, McGwire was an extremely productive hitter over the first half of his career. He was a healthy, full-time player in six of his first eight major league seasons. In five of those years, he topped the 30-homer mark, surpassing 40 on two occasions. He also drove in more than 100 runs three times and was selected to the All-Star Team in each of his six full seasons.

Yet, McGwire batted over .250 in only three of those seasons, and his lifetime batting average stood at only .249. He failed to score as many as 100 runs in a season even once, and he walked 100 times only once. McGwire led the American League in a major statistical category only twice and finished in the top ten in the league MVP balloting only twice, making it into the top five just once. Although McGwire was voted onto six All-Star teams by the fans, he was truly deserving of only two or three of those selections. Furthermore, in no single season, up to that point, was he generally considered to be the best first baseman in the American League.

During the first half of his career, McGwire gradually added approximately 30-35 pounds of muscle onto his frame. However, when he returned to the A’s in 1995 after missing most of the previous season, he appeared significantly larger. McGwire ended up sustaining a season-ending injury once more but, in only 104 games and 317 at-bats that year, hit 39 home runs and drove in 90 runs. The following season, a healthy McGwire returned to hit 52 home runs, knock in 113 runs, score 104 runs, walk 116 times, and bat a career-high .312.

It was the following year, though, in 1997, that

The Legend

of Mark McGwire

truly began. Splitting his season between the Athletics and Cardinals, McGwire hit a major league leading 58 home runs, drove in 123 runs, and batted .274. He was even more dominant in 1998 and 1999. In the first of those years, McGwire established a new major league single-season home run record, shattering Roger Maris’ existing mark of 61, by hitting 70 of his own. He also knocked in 147 runs, scored another 130, walked 162 times, batted .299, and finished second to Sammy Sosa in the league MVP voting. In 1999, McGwire again led the majors in homers, this time with 65. He also knocked in 147 runs for the second consecutive year, scored 118 times, drew 133 bases on balls, and batted .278. That was McGwire’s last great year, however, since injuries relegated him to part-time status in each of the next two seasons, before eventually forcing him into retirement.

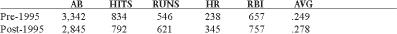

McGwire ended his career with 583 home runs, 1,414 runs batted in, 1,167 runs scored, and a .263 batting average. But, a look at the statistics he posted during the first and second halves of his career is most revealing:

McGwire was clearly far more effective after he returned from the injuries that kept him out of the Oakland lineup for most of the 1993 and 1994 seasons. Over the remainder of his career, he compiled 500 fewer official at-bats. Yet, he hit 107 more home runs, knocked in 100 more runs, scored 75 more runs, and collected only 42 fewer hits. He also batted almost 30 points higher, thereby enabling himself to raise his career average to a respectable .263. Prior to 1995, McGwire averaged a home run every 14 times at-bat. After 1995, that ratio changed to one home run every 8.2 times at-bat. It was also during the latter period that McGwire won three of his four home run titles, led his league in runs batted in for the only time, and finished first in on-base percentage for the only two times. He batted over .300 for the only two times in his career, and scored over 100 runs for the only three times. He finished in the top ten in the league MVP balloting three times after 1995, and was truly among the game’s most dominant players only from 1996 to 1999. He was the best first baseman in baseball in only 1998 and 1999.

Some might suggest that the improvement McGwire displayed during the second half of his career was simply part of his maturation into more of a complete hitter. Others might argue that it merely coincided with the offensive explosion that occurred throughout baseball as a whole at the time. While there may be a certain amount of truth to both arguments, the feeling here is that there were other factors that contributed far more to McGwire’s increased productivity. All one needs to do is to reflect on his physical development into a man of gargantuan-like proportions. During his playing days, McGwire was known to leave bottles of human-growth hormones displayed openly in his locker for all to see. True, those were not steroids, but they certainly provided him with an unfair advantage.

Furthermore, McGwire’s evasive responses at the Congressional hearings held on March 17, 2005 as much as convicted him of using steroids. At those hearings, a relatively lean and frail-looking McGwire repeatedly responded to any references made to his playing days by saying, “I’m not here to talk about the past...I only want to look ahead to the future.”

Yes, Mr. McGwire, with that very statement you incriminated yourself. You were a good player, but you were never the player the American public and the national media made you out to be. Had you not artificially enhanced your performance, you wouldn’t even be considered a borderline Hall of Fame candidate. You do

not

deserve to have your name associated with the all-time greats of the game, and you do

not

belong in the Hall of Fame.

The members of the BBWAA seem to agree, since fewer than 25 percent of them entered McGwire’s name on their ballot for the third consecutive year in 2009.

Rafael Palmeiro

In 2005, Rafael Palmeiro became only the fourth player in major league history to hit more than 500 home runs and compile more than 3,000 hits, joining the select group of Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Eddie Murray. In doing so, he apparently further solidified his status as a future Hall of Famer. At the same time, he made this individual look like a complete fool, since I had previously contended, against popular opinion, that Palmeiro was nothing more than a borderline candidate. Even during the previous few seasons, as Palmeiro drew inexorably closer to 500 home runs—and even after he eventually passed that milestone—I continued to stubbornly maintain that he was not a truly great player, and, therefore, should not be viewed as an obvious Hall of Fame selection no matter how many home runs he went on to hit. I based my opinion on a number of factors.

Most importantly, I felt that it was necessary to judge Palmeiro within the context of his own era. Viewing him in that manner indicated to me that, in spite of his excellent numbers, he never truly distinguished himself as a dominant player. Despite leading his league in hits, doubles, and runs scored one time each, he never finished first in either home runs, runs batted in, or batting average. He finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting only three times, placing no higher than fifth in 1999. He was selected to the All-Star team only four times, a relatively low number for a potential Hall of Famer. In addition, he was never recognized as the best first baseman in the game, and was the American League’s top player at that position only twice, in 1998 and 1999. Finally, I believed it was important to consider that Palmeiro was always fortunate enough to play in excellent hitters’ ballparks, whether it be Chicago’s Wrigley Field, Baltimore’s Camden Yards, or the Ballpark at Arlington, in Texas.

However, when Palmeiro reached the 3,000-hit plateau in 2005, I was forced to concede. The arguments on his behalf became too great. By the end of the season, he was ninth on the all-time home run list, with 569. He had also compiled 1,835 runs batted in, 1,663 runs scored, 3,020 hits, 585 doubles, and a .288 lifetime batting average. He had topped 30 homers 10 times, surpassing 40 on four separate occasions. He had driven in more than 100 runs ten times, including nine straight years at one point. He had also scored more than 100 runs four times, batted over .300 six times, and won three Gold Gloves. The numbers were just too overwhelming to ignore.

But it was also during the 2005 season that Palmeiro tested positive for steroids. Ironically, just a few months earlier, after being implicated by former teammate Jose Canseco in the latter’s book, Palmeiro was the one player at the Congressional hearings to emphatically state his innocence. Looking directly at the members of Congress, and pointing his fingers at them resolutely, Palmeiro said with great conviction, “I have never used steroids...period.”

Perhaps Palmeiro was stupid enough to think he would never get caught. Perhaps he was arrogant enough not to care. Maybe he even believed that, if he was caught, the American public would be naïve enough to think that injecting steroids into his system was something he hadn’t been doing for years. In all likelihood, there are some people gullible enough to believe that. Nevertheless, all available evidence seems to indicate that the numbers Palmeiro compiled during his career were aided considerably by the use of performance-enhancing drugs. Let’s examine the facts:

Palmeiro began his major league career with the Chicago Cubs in 1986. After seeing limited duty his first two seasons, he became a full-time player in 1988. In his only year as a regular in the Chicago starting lineup, Palmeiro batted .307, with only 8 home runs and 53 runs batted in. In 1989, he joined the Texas Rangers, with whom he spent the next five seasons. In his first four years with the team, Palmeiro was a solid, line-drive hitter who showed only occasional glimpses of power. From 1989 to 1992, he batted over .300 twice, scored more than 100 runs once, collected more than 200 hits once, and compiled more than 40 doubles once. However, he never hit more than 26 home runs, totaling as many as 15 only one other time. He also never knocked in more than 89 runs. In 1993, though, Palmeiro experienced a power-surge for the first time in his career. That season, he hit 37 home runs, drove in 105 runs, scored another 124, and batted .295. Coincidentally, Palmeiro’s teammate on the Rangers that year was Jose Canseco, who spent his first full year with the team after being dealt to Texas for Ruben Sierra during the latter stages of the previous campaign.

Palmeiro was traded to Baltimore in 1994 and put up solid numbers during that strike-shortened season. But, over the next nine seasons, splitting his time between Baltimore and Texas, Palmeiro compiled power numbers he seemed completely incapable of earlier in his career. Over that nine-year stretch, he never hit fewer than 38 home runs, surpassing 40 four different times. He also knocked in more than 100 runs in each of those years, compiling at least 120 RBIs on four separate occasions. His two most productive years were with the Rangers in 1999 and 2001. In the first of those years, he hit 47 home runs, knocked in 148 runs, and batted .324. In 2001, he again hit 47 homers, while driving in 123 runs and batting .273.

Those are numbers that, in all likelihood, Palmeiro never would have even approached without the aid of some artificial stimulant. Not only is there Canseco’s accusation, as well as the above evidence to support that theory, but there is also the fact that he tested positive for steroids in 2005. Yet, only a few months earlier, Palmeiro had sat in front of the members of Congress, looked into their faces, pointed his finger at them, and told each and every one of them, “I have never used steroids...period.”

If the rules that theoretically govern the Hall of Fame elections actually do mean anything to the members of the BBWAA, it is inconceivable that any of them could even think of writing Palmeiro’s name onto their ballot. If “integrity” and “character” are indeed qualities that a Hall of Fame candidate should possess, how could they consider electing someone who not only made a mockery of the sport, but also of the United States Congress? Yes, many other players of questionable integrity and character have been admitted to Cooperstown. But they did not perjure themselves before Congress. And they also compiled their statistics legitimately.