Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (51 page)

Clemens pitched exceptionally well for Boston from 1986 to 1992, winning at least 17 games in each of those seasons, and topping 20 victories three times during that stretch. He also allowed fewer than three runs per game in six of those seven years, while striking out more than 200 batters each season and winning three Cy Young Awards. However, his performance began to slip in 1993, one of three consecutive seasons in which injuries forced him to miss several starts. Between 1993 and 1995, Clemens compiled a record of only 30-26, failed to strike out more than 168 batters in any single season, and compiled an ERA below 4.00 only once. After finishing just 10-13 in 1996, despite striking out 257 batters and pitching to a respectable 3.63 ERA, Clemens was allowed to leave Boston by Red Sox management, who believed that the 34-year-old power pitcher’s best days were behind him.

Angered by the lack of interest shown him by the Boston front office, Clemens approached the 1997 campaign with a burning desire to prove he still had several good years left. In his first year in Toronto, Clemens re-established himself as baseball’s best pitcher, capturing his fourth Cy Young Award by leading A.L. starters in virtually every statistical category. However, Clemens got off to a slow start in 1998, compiling a record of only 6-6 in his first 12 decisions.

It was right around that time that Brian McNamee claims he provided Clemens with performance-enhancing drugs for the first time. Clemens finished the season with 14 consecutive victories, to go 20-6 for the year, lead the league again in both strikeouts and ERA, and capture the Cy Young Award for the fifth time. McNamee followed Clemens to New York after the pitcher joined the Yankees in 1999 and claims he injected him with steroids during the latter stages of the 2000 campaign. Clemens was only average during the regular season that year, going 13-8 with a 3.70 ERA. But, after being hit hard by Oakland in the ALDS, Clemens was simply magnificent against Seattle in the ALCS and the Mets in the World Series. In his lone start against the Mariners, Clemens pitched one of the most dominant games in postseason history, allowing only one hit and striking out 15 batters in a complete game shutout. He was almost as good against the Mets in the World Series, allowing only two hits and striking out nine in eight shutout innings. The following season, a 39-year-old Clemens went 20-3 for New York to win the sixth Cy Young Award of his career. After spending two more years with the Yankees, Clemens joined the Houston Astros in 2004 and proceeded to win his seventh Cy Young Award, at the age of 42, by going 18-4, with 218 strikeouts and a 2.98 earned run average. Although he finished only 13-8 the following season, Clemens was arguably more effective than he was in 2004, compiling a brilliant 1.87 ERA.

It could be argued that Clemens’ resurgence after he left Boston at the conclusion of the 1996 campaign was spurred on by his desire to prove Red Sox management wrong. It could also be argued that the outstanding numbers he posted as a member of the Houston Astros were compiled pitching in a weaker league, against inferior lineups. It is also true that Clemens did indeed employ an extremely rigorous exercise routine to stay in top shape. But it is also a fact that his frame grew significantly larger and thicker during the second half of his career, and that much of the success he experienced during that period seemed to coincide with the injections that Brian McNamee claimed he administered to Clemens. Furthermore, it does not seem natural that a pitcher well into his forties would lose very little velocity off his fastball, and would continue to perform at an extremely high level.

Thus, the inevitable conclusion is that Roger Clemens did indeed artificially enhance his performance during the latter stages of his career. The question that follows, then, is whether or not he accomplished enough on his own to be voted into Cooperstown when he eventually becomes eligible for induction. Some members of the BBWAA have already gone on record as saying they will not enter his name on their ballots a few years from now. However, the feeling here is that, despite his duplicity and dishonesty, Clemens deserves to be elected to Cooperstown. Prior to 1998, the year he supposedly used performance-enhancing drugs for the first time, Clemens had already compiled a career record of 213-118, won four Cy Young Awards, been named league MVP once, been selected to six All-Star teams, and led his league in a major statistical category a total of 23 times. While it is extremely doubtful that Clemens would have been able to pitch as well as he did during the second half of his career without the assistance of artificial stimulants, he was a truly dominant pitcher even before he ever debased himself by injecting foreign substances into his system. The baseball writers should consider that fact when Clemens’ name is eventually added to the list of eligible players.

Sammy Sosa

In my first published work,

A Team For The Ages: Baseball’s

All-Time All-Star Team

, I selected the greatest players at each position in the history of the game. First, I named the five greatest players at each position during the first half of the 20th century. Then, I did the same for the period extending from 1951 to 2003. Finally, I named an All-Time Team. When selecting my All-Time Team, I had Sammy Sosa fifth among rightfielders. In naming the team representing the period from 1951 to 2003, I placed Sosa third on the list of rightfielders, behind only Frank Robinson and Roberto Clemente, and just ahead of Tony Gwynn and Reggie Jackson. If I was to make my selections again, Sosa wouldn’t fare nearly as well in the rankings. Since that time, several things have transpired that have caused me to view the slugging outfielder in a very different light.

For one thing, it has become quite apparent that Sosa simply was not a winning player. He was never willing to make the sacrifices necessary to make his team better, and he was always concerned only with his own statistics. He demonstrated that a few years ago when Chicago Cubs Manager Don Baylor suggested to Sosa that he work a little harder to improve his all-around game in order to help the team. He proposed that Sosa lose some of his bulk, cut down a little on his swing, and put forth more of an effort to be a good baserunner and defensive outfielder. Sosa responded by exhibiting the dark side that lay beneath the big, broad smile he always displayed to the general public. Demonstrating the depth of his selfishness, Sosa expressed his anger by chastising his manager in the newspapers, telling the media that Baylor made him feel unappreciated and disrespected. Eventually, Baylor was dismissed from his managerial position.

Sosa further demonstrated his self-absorption in his final year in Chicago. With the Cubs vying for a wild-card spot in the playoffs in 2004, Sosa was in the midst of a terrible second-half slump. Yet, when his manager attempted to drop him to fifth in the Chicago batting order, Sosa once again complained to the press, calling the action a show of “disrespect” to him.

Furthermore, Sosa was never a particularly good all-around player. He was never much of an outfielder, and he was only a good baserunner early in his career. After bulking up considerably early in his tenure with the Cubs, Sosa became a liability, both in the field and on the basepaths. He also was not very selective at the plate, compiling huge strikeout totals while drawing relatively few bases on balls. During his career, Sosa struck out at least 150 times in six different seasons. Meanwhile, he accumulated more than 80 walks only three times.

Yet, all the negatives notwithstanding, it is extremely difficult to overlook the prolific offensive numbers Sosa posted during his career, especially the ones he compiled between 1998 and 2001. Here are his statistics from those four seasons:

1998:

66 HR, 158 RBIs, .308 AVG, 134 RUNS, .647 SLG PCT

1999:

63 HR, 141 RBIs, .288 AVG, 114 RUNS, .635 SLG PCT

2000:

50 HR, 138 RBIs, .320 AVG, 106 RUNS, .634 SLG PCT

2001:

64 HR, 160 RBIs, .328 AVG, 146 RUNS, .737 SLG PCT

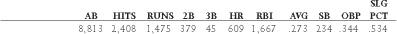

The 243 home runs Sosa hit during that four-year stretch represent the second highest total in baseball history (Mark McGwire hit 245 homers between 1996 and 1999). He was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1998, and also finished second in the balloting in 2001. In all, Sosa topped the 40-homer mark seven times, reaching 30 on four other occasions. He also knocked in more than 100 runs nine times, scored more than 100 runs five times, and batted over .300 four times. Upon his retirement at the conclusion of the 2007 campaign, these were his career numbers:

Those 609 home runs place Sosa sixth on the all-time list. He also was a league-leader in a major statistical category a total of seven times, was selected to seven All-Star teams, and finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting seven different times. Furthermore, between 1998 and 2001, he was most certainly considered to be one of the elite players in the game. Thus, Sosa clearly has the necessary qualifications of a desirable Hall of Fame candidate.

However, there is one additional factor that must be considered. When I made my selections for my All-Time All-Star Team, I had reservations about including Sosa. Even though major league baseball had yet to institute any kind of formal investigative procedure, there was already widespread speculation as to which players might be involved with the use of performance-enhancing drugs. And Sosa’s name was at the top of everyone’s list. Although I chose to give him the benefit of the doubt when formulating the rankings for my book, I was extremely suspicious of Sosa, very much doubting the integrity of his offensive numbers. The progression of Sosa’s career, as well as the development of his physique, both contributed greatly to my skepticism. Let’s take a closer look at both.

When Sosa first entered the major leagues as a member of the Texas Rangers in 1989, he was a relatively thin 20-year old, with good running speed and only marginal home run power. He was traded to the Chicago White Sox later that year, and spent the next two seasons with the Sox, playing as a regular in one of them. In that season, Sosa hit 15 home runs, drove in 70 runs, scored 72 others, batted only .233, and struck out 150 times. Prior to the start of the 1992 campaign, the 23-year-old Sosa was dealt to the cross-town Cubs, for whom he appeared in only 67 games. In 262 at-bats, he hit only 8 home runs, drove in 25 runs, and batted .260. In 1993, a more physically mature 24-year-old Sosa became a regular in the Cubs starting lineup, hitting 33 home runs, knocking in 93 runs, scoring 92 others, batting .261, and stealing 36 bases. Over the next three seasons, Sosa continued to develop into more of a complete offensive player. In the strike-shortened 1994 campaign, he hit 25 home runs, drove in 70 runs, batted .300, and stole 22 bases. In 1995, he hit 36 home runs, knocked in 119 runs, batted .268, and stole 34 bases. In 1996, he hit 40 homers, drove in 100 runs, batted .273, and stole 18 bases. Sosa had another productive year in 1997, hitting 36 home runs, knocking in 119 runs, batting .251, and stealing 22 bases. It was in the following season, though, that he began his amazing run.

However, it was a few years earlier, during the mid-90s, that Sosa began adding a great deal of bulk to his frame. Indeed, he eventually developed a massive physique that was much larger than the one he carried just a few years earlier. Was this merely the result of advanced weight training, or was he perhaps using some form of performance-enhancing drug? Sosa would have us believe the former, especially since he did not test positive for steroids after baseball instituted its testing policy in 2005. But everything about the man suggests he used steroids to create additional body mass and greatly enhance his performance. After all, anyone who would cork his bat to get an edge would likely cheat in any number of other ways.

Furthermore, Sosa’s evasiveness at the Congressional hearings, as well as the utter disdain he displayed for the entire proceedings, indicated that he must have something to hide. He schemingly had his opening statement read by his attorney, claiming in a prepared statement that he didn’t wish to address the members of Congress directly since he was concerned that his poor English might cause his words to be misinterpreted. However, anyone familiar with Sosa knows that he speaks the English language quite well. He certainly never had any problems promoting himself to the media, or expressing his disdain for his managers to the press. Then, every time the members of Congress posed a question to Sosa, he responded by stating, “I agree with what Mark (McGwire) just said.” Well, Sammy, that might have meant something, except for the fact that Mark never said anything. All McGwire kept reiterating was that he wasn’t there to talk about the past.

Thus, we are left with someone who, based purely on statistics, deserves to be enshrined in Cooperstown, yet whose suspected use of steroids will undoubtedly place a huge question mark in the minds of most voters when he eventually becomes eligible for induction. Still, there will be those who consider this a no-brainer. They will say, “How could you even think about keeping someone out who has accomplished the things that Sosa has?” Since Sosa never tested positive for steroids he is likely to be elected to the Hall of Fame some time during his period of eligibility. That will be the politically correct thing to do, and most of the writers will probably not have the courage to do anything else. They will not have it in them to exclude from their ballots someone who compiled the kind of numbers Sosa did during his career. And they will not have the courage to ignore someone who is so revered throughout the Latino community. Hopefully, though, there will be others who feel as I do. They will have too many concerns about the legitimacy of Sosa’s accomplishments to view him as a worthy Hall of Famer, and they will choose not to vote for him.