Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (109 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

40

. John Gibbon,

Personal Recollections of the Civil War

(New York, 1928), 73.

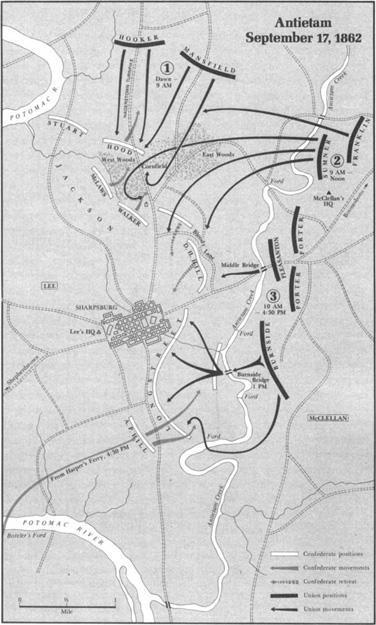

Although the half of Lee's army north of the Potomac had warded off disaster, the invasion of Maryland appeared doomed. The whole Union army would be across South Mountain next day. The only apparent Confederate option seemed to be retreat into the Shenandoah Valley. But when Lee received word that Jackson expected to capture Harper's Ferry on September 15, he changed his mind about retreating. He ordered the whole army to concentrate at Sharpsburg, a Maryland village about a mile from the Potomac. Lee had decided to offer battle. To return to Virginia without fighting would mean loss of face. It might endanger diplomatic efforts to win foreign recognition. It would depress southern morale. Having beaten the Federals twice before, Lee thought he could do it again—for he still believed the Army of the Potomac to be demoralized.

Lee's estimate of northern morale seemed to be confirmed by Jackson's easy capture of Harper's Ferry. The Union garrison was composed mostly of new troops under a second-rate commander—Colonel Dixon Miles, a Marylander who had been reprimanded for drunkenness at First Bull Run and whose defense of Harper's Ferry was so inept as to arouse suspicions of treason. Killed in the last exchange of fire before the surrender, Miles did not have to defend himself against such a charge. As Jackson rode into town dressed as usual in a nondescript uniform and battered fatigue cap, one of the disarmed Union soldiers said, "Boys, he's not much for looks, but if we'd had him we wouldn't have been caught in this trap!"

41

The various Confederate units that had besieged Harper's Ferry marched as fast as possible for Sharpsburg fifteen miles away. Until they arrived on September 16 and 17, Lee had only three divisions in line with their backs to the Potomac over which only one ford offered an escape in case of defeat. During September 15 the Army of the Potomac began arriving at Antietam Creek a mile or two east of Lee's position. Still acting with the caution befitting his estimate of Lee's superior force, McClellan launched no probing attacks and sent no cavalry reconnaisance across the creek to determine Confederate strength. On September

41

. Henry Kyd Douglas, "Stonewall Jackson in Maryland,"

Battles and Leaders

, II, 627. Paul R. Teetor, A

Matter of Hours: Treason at Harper's Ferry

(Rutherford, N.J., 1982), argues from circumstantial evidence that Miles deliberately sabotaged the defense of the garrison. A retired judge who presents his argument in the manner of a brief against Miles, Teetor cannot be said to have "proved" his case though he has raised several disturbing questions.

16 the northern commander had 60,000 men on hand and another 15,000 within six miles to confront Lee's 25,000 or 30,000. Having informed Washington that he would crush Lee's army in detail while it was separated, McClellan missed his second chance to do so on the 16th while he matured plans for an attack on the morrow. Late that afternoon—as two more Confederate divisions slogged northward from Harper's Ferry—McClellan sent two corps across the Antietam north of the Confederate left, precipitating a sharp little fight that alerted Lee to the point of the initial Union attack at dawn next day.

Antietam (called Sharpsburg by the South) was one of the few battles of the war in which both commanders deliberately chose the field and planned their tactics beforehand. Instead of entrenching, the Confederates utilized the cover of small groves, rock outcroppings, stone walls, dips and swells in the rolling farmland, and a sunken road in the center of their line. Only the southernmost of three bridges over the Antietam was within rebel rifle range; this bridge would become one of the keys to the battle. McClellan massed three corps on the Union right to deliver the initial attack and placed Burnside's large gth Corps on the left with orders to create a diversion to prevent Lee from transferring troops from this sector to reinforce his left. McClellan held four Union divisions and the cavalry in reserve behind the right and center to exploit any breakthrough. He also expected Burnside to cross the creek and roll up the Confederate right if opportunity offered. It was a good battle plan and if well executed it might have accomplished Lincoln's wish to "destroy the rebel army."

But it was not well executed. On the Union side the responsibility for this lay mainly on the shoulders of McClellan and Burnside. McClellan failed to coordinate the attacks on the right, which therefore went forward in three stages instead of simultaneously. This allowed Lee time to shift troops from quiet sectors to meet the attacks. The Union commander also failed to send in the reserves when the bluecoats did manage to achieve a breakthrough in the center. Burnside wasted the morning and part of the afternoon crossing the stubbornly defended bridge when his men could have waded the nearby fords against little opposition. As a result of Burnside's tardiness, Lee was able to shift a division in the morning from the Confederate right to the hard-pressed left where it arrived just in time to break the third wave of the Union attack. On the Confederate side the credit for averting disaster belonged to the skillful generalship of Lee and his subordinates but above all to the desperate courage of men in the ranks. "It is beyond all wonder," wrote a Union officer after the battle, "how such men as the rebel troops can fight on as they do; that, filthy, sick, hungry, and miserable, they should prove such heroes in fight, is past explanation."

42

The fighting at Antietam was among the hardest of the war. The Army of the Potomac battled with grim determination to expunge the dishonor of previous defeats. Yankee soldiers were not impelled by fearless bravery or driven by iron discipline. Few men ever experience the former and Civil War soldiers scarcely knew the latter. Rather, they were motivated in the mass by the potential shame of another defeat and in small groups by the potential shame of cowardice in the eyes of comrades. A northern soldier who fought at Antietam gave as good an explanation of behavior in battle as one is likely to find anywhere. "We heard all through the war that the army 'was eager to be led against the enemy,' " he wrote with a nice sense of irony. "It must have been so, for truthful correspondents said so, and editors confirmed it. But when you came to hunt for this particular itch, it was always the next regiment that had it. The truth is, when bullets are whacking against tree-trunks and solid shot are cracking skulls like egg-shells, the consuming passion in the breast of the average man is to get out of the way. Between the physical fear of going forward and the moral fear of turning back, there is a predicament of exceptional awkwardness." But when the order came to go forward, his regiment did not falter. "In a second the air was full of the hiss of bullets and the hurtle of grape-shot. The mental strain was so great that I saw at that moment the singular effect mentioned, I think, in the life of Goethe on a similar occasion—the whole landscape for an instant turned slightly red." This psychological state produced a sort of fighting madness in many men, a superadrenalized fury that turned them into mindless killing machines heedless of the normal instinct of self-preservation. This frenzy seems to have prevailed at Antietam on a greater scale than in any previous Civil War battle. "The men are loading and firing with demonaical fury and shouting and laughing hysterically," wrote a Union officer in the present tense a quarter-century later as if that moment of red-sky madness lived in him yet.

43

42

. Murfin,

The Gleam of Bayonets

, 250.

43

. David L. Thompson, "With Burnside at Antietam,"

Battles and Leaders

, II, 661–62; Rufus R. Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin, quoted in Murfin,

The Gleam of Bayonets

, 218. The 6th Wisconsin, a regiment in the Iron Brigade, lost 40 men killed and 112 wounded out of about 300 engaged at Antietam.

Joseph Hooker's Union 1st Corps led the attack at dawn by sweeping down the Hagerstown Pike from the north. Rebels waited for them in what came to be known as the West Woods and The Cornfield just north of a whitewashed church of the pacifist Dunkard sect. "Fighting Joe" Hooker—an aggressive, egotistical general who aspired to command the Army of the Potomac—had earned his sobriquet on the Peninsula. He confirmed it here. His men drove back Jackson's corps from the cornfield and pike, dealing out such punishment that Lee sent reinforcements from D. H. Hill's division in the center and Longstreet's corps on the right. These units counterpunched with a blow that shattered Hooker's corps before the Union 12th Corps launched the second wave of the northern assault. This attack also penetrated the Confederate lines around the Dunkard Church before being hurled back with heavy losses, whereupon a third wave led by a crack division of "Bull" Sumner's 2nd Corps broke through the rebel line in the West Woods. Before these bluecoats could roll up the flank, however, one Confederate division that had arrived that morning from Harper's Ferry and another that Lee had shifted from the inactive right near Burnside's bridge suddenly popped out in front, flank, and rear of Sumner's division and all but wiped it out with a surprise counterattack. Severely wounded and left for dead in this action was a young captain in the 20th Massachusetts, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

For five hours a dreadful slaughter raged on the Confederate left. Twelve thousand men lay dead and wounded. Five Union and five Confederate divisions had been so cut up that they backed off as if by mutual consent and did no more serious fighting this day. In the meantime Sumner's other two divisions had obliqued left to deal with a threat to their flank from Confederates in a sunken farm road southeast of the Dunkard Church. This brought on the midday phase of the battle in which blue and gray slugged it out for this key to the rebel center, known ever after as Bloody Lane. The weight of numbers and firepower finally enabled the blue to prevail. Broken southern brigades fell back to regroup in the outskirts of Sharpsburg itself. A northern war correspondent who came up to Bloody Lane minutes after the Federals captured it could scarcely find words to describe this "ghastly spectacle" where "Confederates had gone down as the grass falls before the scythe."

44

Now was the time for McClellan to send in his reserves. The enemy center was wide open. "There was no body of Confederate infantry in

44

. Charles Carleton Coffin, "Antietam Scenes,"

Battles and Leaders

, II, 684.

this part of the field that could have resisted a serious advance," wrote a southern officer. "Lee's army was ruined, and the end of the Confederacy was in sight," added another.

45

But the carnage suffered by three Union corps during the morning had shaken McClellan. He decided not to send in the fresh 6th Corps commanded by Franklin, who was eager to go forward. Believing that Lee must be massing his supposedly enormous reserves for a counterattack, McClellan told Franklin that "it would not be prudent to make the attack."

46

So the center of the battlefield fell silent as events on the Confederate right moved toward a new climax.

All morning a thin brigade of Georgians hidden behind trees and a stone wall had carried on target practice against Yankee regiments trying to cross Burnside's bridge. The southern brigade commander was Robert A. Toombs, who enjoyed here his finest hour as a soldier. Disappointed by his failure to become president of the Confederacy, bored by his job as secretary of state, Toombs had taken a brigadier's commission to seek the fame and glory to which he felt destined. Reprimanded more than once by superiors for inefficiency and insubordination, Toombs spent many of his leisure hours denouncing Jefferson Davis and the "West Point clique" who were ruining army and country. For his achievement in holding Burnside's whole corps for several hours at Antietam—and being wounded in the process—Toombs expected promotion, but did not get it and subsequently resigned to go public with his anti-administration exhortations.

In the early afternoon of September 17 two of Burnside's crack regiments finally charged across the bridge at a run, taking heavy losses to establish a bridgehead on the rebel side. Other units found fords about the same time, and by mid-afternoon three of Burnside's divisions were driving the rebels in that sector back toward Sharpsburg and threatening to cut the road to the only ford over the Potomac. Here was another crisis for Lee and an opportunity for McClellan. Fitz-John Porter's 5th Corps stood available as a reserve to support Burnside's advance. One of Porter's division commanders urged McClellan to send him in to bolster Burnside. McClellan hesitated and seemed about to give the order when he looked at Porter, who shook his head. "Remember, General," Porter was heard to say, "I command the last reserve of the last