Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (107 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

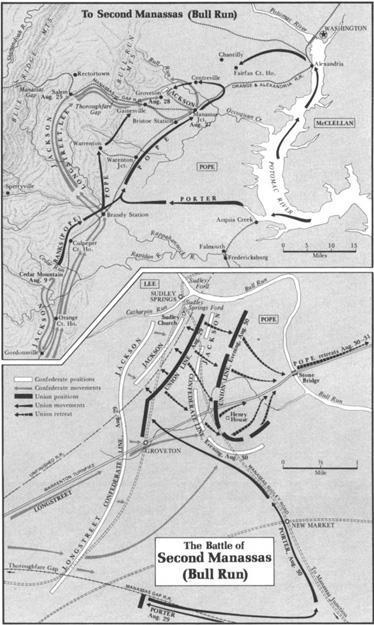

For Jackson had reverted from the sluggard of the Chickahominy to the gladiator of the Valley. Indeed, the Valley was where Pope thought the rebels were heading when his scouts detected Jackson's march northwestward along the Rappahannock on August 25. But Pope's under-strength cavalry failed to detect Jackson's turn to the east on August 26, when he marched unopposed along the railroad to Manassas, the main Union supply base twenty-five miles behind Pope. In one of the war's great marches, Jackson's whole corps—24,000 men—had covered more than fifty miles in two days. The hungry, threadbare rebels swooped down on the mountain of supplies at Manassas like a plague of grasshoppers. After eating their fill and taking everything they could carry away, they put the torch to the rest.

The accumulation of supplies at Manassas and the maintenance of the vulnerable single-track line that linked Pope to his base had been the work of Herman Haupt, the war's wizard of railroading. The brusque, no-nonsense Haupt was chief of construction and transportation for the U.S. Military Rail Roads in Virginia. He had brought order out of chaos in train movements. He had rebuilt destroyed bridges in record time. His greatest achievement had been the construction from green logs and saplings of a trestle 80 feet high and 400 feet long with unskilled soldier labor in less than two weeks. After looking at this bridge, Lincoln said: "I have seen the most remarkable structure that human eyes ever rested upon. That man, Haupt, has built a bridge . . . over which loaded trains are running every hour, and upon my word, gentlemen, there is nothing in it but beanpoles and cornstalks."

25

Haupt developed prefabricated parts for bridges and organized the first of the Union construction corps that performed prodigies of railroad and bridge building in the next three years. Their motto, like that of their Seabee descendants in World War II, might have been: "The difficult we can do immediately; the impossible will take a little longer." As an awed contraband put it, "the Yankees can build bridges quicker than the Rebs can burn them down."

26

Within four days Haupt had trains running over the line Jackson had cut. But unfortunately for the North, Pope's military abilities did not match Haupt's engineering genius. Still confident and aggressive, Pope saw Jackson's raid as an opportunity to "bag" Jackson before the other half of Lee's army could join him. The only problem was to find the slippery Stonewall. After burning the supply depot at Manassas, Jackson's troops disappeared. Pope's overworked cavalry reported the rebels to be at various places. This produced a stream of orders and countermanding orders to the fragmented corps of three commands: his own,

25

. Francis A. Lord,

Lincoln's Railroad Man: Herman Haupt

(Rutherford, N.J., 1969), 77.

26

. Turner,

Victory Rode the Rails

, Frontispiece.

two corps of the Army of the Potomac sent to reinforce him, and part of Burnside's 9th Corps which had been transferred from the North Carolina coast.

One of the Army of the Potomac units moving up to support Pope was Fitz-John Porter's corps, whose commander had called Pope an Ass and who had recently written in another private letter: "Would that this army was in Washington to rid us of incumbents ruining our country."

27

During this fateful August 28, Porter's friend McClellan was at Alexandria resisting Halleck's orders to hurry forward another Army of the Potomac corps to Pope's aid. McClellan shocked the president with a suggestion that all available troops be held under his command to defend Washington, leaving Pope "to get out of his scrape by himself." If "Pope is beaten," wrote McClellan to his wife, "they may want me to save Washington again. Nothing but their fears will induce them to give me any command of importance."

28

Almost broken down by worry, Halleck failed to assert his authority over McClellan. Thus two of the best corps in the Army of the Potomac remained within marching distance of Pope but took no part in the ensuing battle.

Meanwhile Jackson's troops had gone to ground on a wooded ridge a couple of miles west of the old Manassas battlefield. Lee and Longstreet with the rest of the army were only a few miles away, having broken through a gap in the Bull Run Mountains which Pope had neglected to defend with a sufficient force. Stuart's cavalry had maintained liaison between Lee and Jackson, so the latter knew that Longstreet's advance units would join him on the morning of August 29.

The previous evening one of Pope's divisions had stumbled onto Jackson's hiding place. In a fierce firefight at dusk the outnumbered blue-coats had inflicted considerable damage before withdrawing in a battered condition themselves. Conspicuous in this action was an all-western brigade (one Indiana and three Wisconsin regiments) that soon earned a reputation as one of the best units in the army and became known as the Iron Brigade. By the war's end it suffered a higher percentage of casualties than any other brigade in the Union armies—a distinction matched by one of the units it fought against on this and other battle-

27

. Porter to Manton Marble, Aug. 10, 1862, quoted in T. Harry Williams,

Lincoln and His Generals

(New York, 1952), 148.

28

.

CWL

, V, 399; Dennett,

Lincoln/Hay

, 45; McClellan to Ellen McClellan, Aug. 22,1862, McClellan Papers.

fields, the all-Virginia Stonewall Brigade, which experienced more casualties than any other Confederate brigade.

Having found Jackson, Pope brought his scattered corps together by forced marches during the night and morning of August 28–29. Because he thought that Jackson was preparing to retreat toward Longstreet (when in fact Longstreet was advancing toward Jackson), Pope committed an error. Instead of waiting until he had concentrated a large force in front of Jackson, he hurled his divisions one after another in piecemeal assaults against troops who instead of retreating were ensconced in ready-made trenches formed by the cuts and fills of an unfinished railroad. The Yankees came on with fatalistic fury and almost broke Jackson's line several times. But the rebels hung on grimly and threw them back.

Pope managed to get no more than 32,000 men into action against Jackson's 22,000 on August 29. The fault was not entirely his. Coming up on the Union left during the morning were another 30,000 in McDowell's large corps and Porter's smaller one. McDowell maneuvered ineffectually during the entire day; only after dark did a few of his regiments get into a moonlight skirmish with the enemy. As for Porter, his state of mind this day is hard to fathom. He believed that Long-street's entire corps was in his front—as indeed it was by noon—and therefore with 10,000 men Porter did nothing while thousands of other northern soldiers were fighting and dying two miles away. Not realizing that Longstreet's corps had arrived, Pope ordered Porter in late afternoon to attack Jackson's right flank. Porter could not obey because Longstreet connected with Jackson's flank; besides, Porter had no respect for Pope and resented taking orders from him, so he continued to do nothing. For this he was later court-martialed and cashiered from the service.

29

29

. Porter remained in command of the 5th Corps until November, when he was ordered before the court-martial, which convicted him. After the war the cashiered general repeatedly sought a new trial and finally won reversal of the verdict in 1886, when testimony by Confederate officers and the evidence provided by captured southern records demonstrated that Longstreet had indeed been in Porter's front and that the Union general therefore could not have obeyed Pope's order. To some degree Porter was the victim of Republican attacks on McClellan and his associates, of whom Porter was the closest. But Porter's failure to do

anything

with his corps on August 29 deserved at least mild censure. For a study of this affair that is sympathetic to Porter, see Otto Eisenschiml,

The Celebrated Case of Fitz-John Porter

(Indianapolis, 1950); for brief critical appraisals, see Kenneth P. Williams,

Lincoln Finds a General

, 5 vols. (New York, 1949–59), I, 324–30, II, 785–89; and Catton,

Terrible Swift Sword

, 522–23.

While Pope fought only with his right hand on August 29, Lee parried only with his left. When Longstreet got his 30,000 men in line during the early afternoon, Lee asked him to go forward in an attack to relieve the pressure on Jackson. But Longstreet demurred, pointing out that a Union force of unknown strength (Porter and McDowell) was out there somewhere in the woods. Unlike Lee and Jackson, Longstreet preferred to fight on the defensive and hoped to induce these Federals to attack

him

. Lee deferred to his subordinate's judgment. Thus while Longstreet's presence neutralized 30,000 Federals, they also neutralized Longstreet.

That night a few Confederate brigades pulled back from advanced positions to readjust their line. Having made several wrong guesses about the enemy's intentions during the past few days, Pope guessed wrong again when he assumed this movement to be preliminary to a retreat. He wanted so much to "see the backs of our enemies"—as he had professed always to have done in the West—that he believed it about to happen. He sent a victory dispatch to Washington and prepared to pursue the supposedly retreating rebels.

But when Pope's pursuit began next day the bluecoats went no more than a few hundred yards before being stopped in their tracks by bullets from Jackson's infantry still holding their roadbed trenches. The Federals hesitated only momentarily before attacking in even heavier force than the previous day. The exhausted southerners bent and almost broke. Some units ran out of ammunition and resorted to throwing rocks at the Yankees. Jackson was forced to swallow his pride and call on Long-street for reinforcements. Longstreet had a better idea. He brought up artillery to enfilade the Union attackers and then hurled all five of his divisions in a screaming counterattack against the Union left, which had been weakened by Pope's shift of troops to his right for the assaults on Jackson. Once Longstreet's men went into action they hit the surprised northerners like a giant hammer. Until sunset a furious contest raged all along the line. The bluecoats fell back doggedly to Henry House Hill, scene of the hardest fighting in that first battle in these parts thirteen months earlier. Here they made a twilight stand that brought the rebel juggernaut to a halt.

That night Pope—all boastfulness gone—decided to pull back toward Washington. On September 1 two blue divisions fought a vicious rearguard action at Chantilly, only twenty miles from Washington, against Jackson's weary corps which Lee had sent on another clockwise march for one final attempt to hit the retreating Union flank. After warding off this thrust in a drenching thunderstorm, the beaten-down bluecoats trudged into the capital's defenses. During the previous five days they had suffered 16,000 casualties out of a total force of 65,000, while Lee's 55,000 had lost fewer than 10,000 men. Lee's achievement in his second strategic offensive was even more remarkable than in his first. Less than a month earlier the main Union army had been only twenty miles from Richmond. With half as many troops as his two opponents (Pope and McClellan), Lee had shifted the scene to twenty miles from Washington, where the rebels seemed poised for the kill.

Behind Union lines all was confusion. When news of the fighting reached Washington, Secretary of War Stanton appealed for volunteer nurses to go out to help with the wounded. Many government clerks and other civilians responded, but a portion of them—a male portion—turned out to be worse than useless. Some were drunk by the time they reached the front, where they bribed a few ambulance drivers with whiskey to take

them

back to Washington instead of the wounded. To this shameful episode should be contrasted the herculean labors of Herman Haupt, who sent trains through the chaos to bring back wounded men, and the sleepless work of numerous women nurses headed by Clara Barton. "The men were brot down from the field and laid on the ground beside the train and so back up the hill 'till they covered acres," wrote Barton a few days later. The nurses opened hay bales and spread the hay on the ground to provide bedding. "By midnight there must have been

three thousand

helpless men lying in that hay. . . . All night we made compresses and slings—and bound up and wet wounds, when we could get water, fed what we could, travelled miles in that dark over these poor helpless wretches, in terror lest some one's candle fall

into the hay

and consume them all."

30