Battleship Bismarck (43 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

The alarm bells were still ringing when, returning from the bridge, I entered my action station. I picked up the control telephone and heard, “Two battleships port bow.” I turned my director and saw two bulky silhouettes, unmistakably the

King George V

and

Rodney

, at a range of approximately 24,000 meters. As imperturbable as though they were on their way to an execution, they were coming directly towards us in line abreast, a good way apart, their course straight as a die. The seconds ticked by. Tension and anticipation mounted. But the effect was not what Tovey hoped for. The nerves of our gun directors, gun captains, and range-finding personnel were steady. After the utterly hopeless night they had just spent, any action could only be a release. The very first salvo would bring it. How many ships were approaching no longer meant anything; we could be shot to pieces only once.

Our eight 38-centimeter guns were now opposed to nine 40.6-centimeter and ten 35.6-centimeter guns; our twelve 15-centimeter guns by twenty-eight 15.2-centimeter and 13.3-centimeter guns. A single British broadside weighed 18,448 kilograms (20,306 kilograms, including the sixteen 20.3-centimeter guns on the heavy cruisers,

Norfolk

and

Dorsetshire

) against 6,904 kilograms for a German broadside.

*

In our foretop Schneider was giving orders in his usual calm voice. He announced that our target was the

Rodney

, which was off our port bow and heading straight for us. Then, to the ship’s command, “Main and secondary batteries ready, request permission to fire.” But it was the

Rodney

that got off the first salvo, at 0847. The

King George V’

s first salvo followed one minute later.

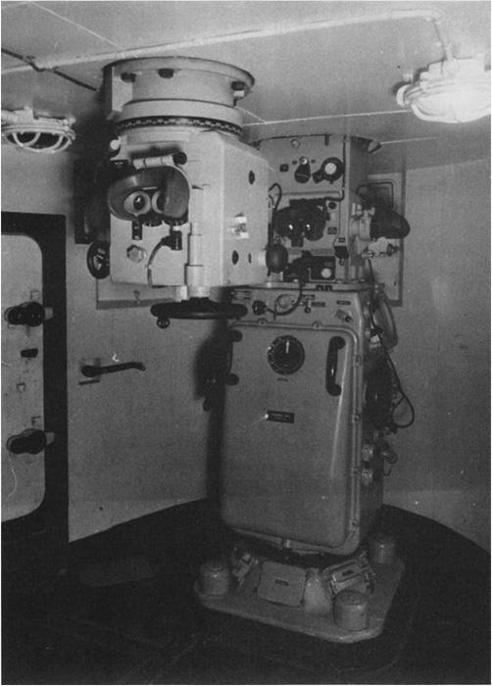

The battleship

Rodney

looses a salvo on the

Bismarck

during the action on 27 May. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

The range had closed to less than 20,000 meters, at which distance the time of flight of the shells was less than one minute, but it seemed many times that long. Finally, white mushrooms, tons of water thrown up by heavy shells, rose seventy meters into the air. But they were still quite far from us. At 0849 the

Bismarck’s

fore turrets replied with a partial salvo at the

Rodney

. At this time, our after turrets could not be brought to bear on the target. Schneider observed his first three salvos as successively “short,” “straddling,” and “over,” an extremely promising start that I only knew about from what I heard on the telephone because the swinging back and forth of the

Bismarck

allowed me only intermittent glimpses of the enemy. Obviously not considering dividing our fire, he continued to concentrate on the

Rodney

.

As the shells hurtled past one another in the air, I tried to distinguish incoming ones from those being discharged from our own guns. Suddenly I remembered wardroom conversations that I had had with British naval officers regarding range-finding techniques. They had high praise for their prismatic instruments while I praised our stereoscopic ones. Did we have the better principle? The

Rodney

seemed to need a lot of time to find our range.

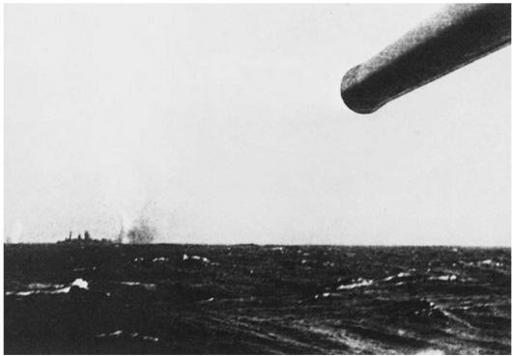

The battleships

Rodney

and

Bismarck

in action on 27 May. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

I spent the first few minutes of the battle wondering why no enemy shells were landing on us, but that soon changed and there were more than enough of them. At 0854 the

Norfolk

, which was off the

Bismarck’s

starboard bow, began firing her 20.3-centimeter battery at a range of 20,000 meters forward of the starboard quarter. A few minutes later, the

Rodney

opened up with her secondary battery and, around 0902, she observed a spectacular hit on the forward part of the

Bismarck

. At 0904 the

Dorsetshire

began firing on us at a range of 18,000 meters from the starboard side, astern. The

Bismarck

was under fire from all directions, and the British were having what amounted to undisturbed target practice.

Not long after the action began the

King George V

and, a little later, the

Rodney

gradually turned to starboard onto a southerly course, where they maneuvered so as to stay on our port side. This tactic caused the range to diminish with extraordinary rapidity, which seemed to be exactly what Tovey wanted. Lindemann could no longer maneuver so as to direct, or at least influence, the tactical course of the battle. He could neither choose his course nor evade the enemy’s fire. Tovey, on the other hand, could base his tactical decisions on the sure knowledge that our course would continue to be into the wind. We could not steer even this course to the best advantage of our gunners, who were faced with great difficulty in correcting direction. Though I could not see what was going on around me from my completely enclosed, armored control station, it was not hard to picture how the scene outside was changing. As the range decreased, the more frequent became the

harrumphs

of incoming shells and the louder grew the noise of battle. Our secondary battery, as well as those of the enemy, had gone into action. Only our antiaircraft guns, which had no targets of their own and were useless in a close engagement between battleships, were silent. At first, their crews were held as replacements for casualties at other guns, and were stationed in protected rooms set aside for them. These “protected rooms,” however, being on the main deck and not heavily armored, provided little protection even against shell splinters, let alone direct hits at the ranges this battle was fought.

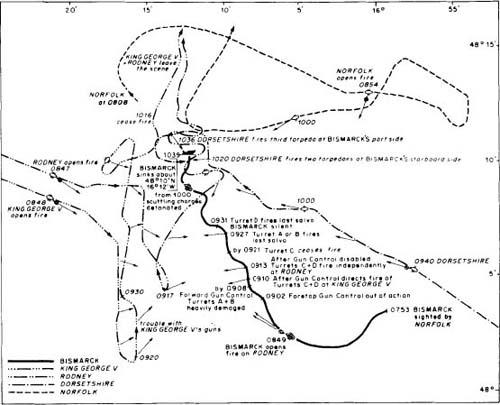

From 0753, German Summer Time, to 1039, German Summer Time, on 27 May. The last battle. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

When perhaps twenty minutes had passed since the firing of the first salvos, I searched the horizon through my starboard director for other hostile ships. Off our starboard bow, I made out a cruiser, the

Norfolk

, which by chance had just stopped firing. We had not fired on her because Schneider and Albrecht were still concentrating on the battleships, which were off our port bow and at that moment not visible from aft. No sooner had I begun to wonder whether, with so many enemies around us, our ship’s command would decide to divide our fire, than I received an indirect answer. Cardinal came on the control telephone and said that the main fire-control station in the foretop was out of action or, at any rate, could not be contacted, that turrets Anton and Bruno were out of action, and that I was to take over control of turrets Caesar and Dora from aft. He said nothing about the forward fire-control station. I supposed that it would continue to direct the secondary battery, unless it had been disabled, which seemed not unlikely in view of the number of times the forward section of the ship had been hit. There was not time to ask long questions and, since I was not given a target, I had a completely free hand.

An observer in the

Norfolk

saw both barrels of turret Anton fall to maximum depression as though its elevating mechanism had been hit. The barrels of turret Bruno, he commented, were trained to port and pointing high into the air.

“Action circuit aft,”

*

I announced and, beginning forward, scanned

the horizon through my port director. Strangely enough, there was no trace of the

Rodney

, which I had not seen to starboard, either. She must have been in the dead space forward of my station. But there, steaming on a reciprocal course and now a bit abaft our beam, was the

King George V

. She was about 11,000 meters distant—near enough to touch, almost like a drill in the Baltic. “Passing fight to port, target is the battleship at 250°,” I told the after computer room and, upon receiving the “ready” report from below, “One salvo.”

Boom!

It went off and during the approximately twenty seconds that it was in the air, I added, “Battleship bow left, one point off, enemy speed 20 knots.”

The excellent visibility would be a great help in finding the range quickly, I thought, which was particularly important because the target was rapidly passing astern of us. “Attention, fall,” announced the computer room. “Two questionably right, two right wide, questionably over,” I observed, then ordered, “Ten more left, down four, a salvo.”

Boom!

. . . “Attention, fall” . . . “Middle over” . . . “Down four, a salvo” . . . “Attention, fall” . . . “Middle short” . . . and, full of anticipation, “Up two, good rapid!” Then again our shot fell and the four columns of water began to rise . . . quarter, half, three-quarters of the way, at which point they were useful for observation, “Three over, one short,” I never did see the splashes reach their full height. Lieutenant Commander Hugh Guernsey, in the

King George V

, heard my fourth salvo whistle over and, wondering if the next one would be a hit, involuntarily took a step back behind a splinter shield.

My aft director gave a violent shudder, and my two petty officers and I had our heads bounced hard against the eyepieces. What did that? When I tried to get my target in view again, it wasn’t there; all I could see was blue. I was looking at something one didn’t normally see, the “blue layer” baked on the surface of the lenses and mirrors to make the picture clearer. My director had been shattered. Damn! I had just found the range of my target and now I was out of the battle. Though no one in the station was hurt, our instruments were ruined. Obviously, a heavy shell had passed low over our station and carried away anything that protruded. We tested all our optics and couldn’t see our targets through any of them. I walked under the ladder to the cupola and looked up towards our large range-finder and its operators. There was nothing there. Nothing at all. What only a moment before was a complete array had vanished without a trace. A heavy shell had ripped through the middle of the cupola, whose jagged ruin allowed a clear view of the cloudy sky. From the

Rodney?

The

King George V?

Who knows? It made no difference. My God, we said to ourselves, that was close. Two meters lower and it could have been the end of us. The armor of our station would not have been enough protection against a direct hit at that range.