Battleship Bismarck (44 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

The interior of one of the

Bismarck’s

armored fire-control stations, such as the author occupied at general quarters. The light-colored instrument mounted in the overhead is an observation periscope-telescope for the range-finder officer. Behind it, the darker, tall instrument is a gun director. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

Nothing could have been more devastating to me than being put out of action just when I had every hope of hitting the

King George V

. For our ship, that was the end of all central fire control. I called both computer rooms, but neither of them could get through to the forward fire-control station. The only thing to do was let turrets Caesar and Dora fire independently. My station being blind, I told their commanders that they were free to choose their targets.

At 0916, shortly after loosing six torpedoes from a distance of about 10,000 meters, all of which missed us, the

Rodney

turned to a northerly course and became the target chosen by our turret commanders. This choice was made apparently because the range to the

Rodney

, which did not go as far to the south as the

King George V

, had closed to 7,500 meters.

*

The last shots of our after turrets were not badly aimed; a few shells fell very near the

Rodney

. At 0927, one of our fore turrets, either Anton or Bruno, fired one more salvo, but the firing became irregular and finally petered out.

†

First turret Dora and then Caesar fell silent. At 0931 the

Bismarck’s

main battery fired its last salvo.

Our list to port had increased a bit while the firing was going on. Around 0930, gas and smoke began to drift through our station, causing us to put on gas masks from time to time. But it wasn’t too bad.

Unable to leave our station because an inferno was raging outside, we knew little about what was going on elsewhere. Was the ship’s command still in the forward command post? Was Lindemann still in charge there? No reports came down to us nor were we asked what was happening in our area. We had not heard a single word from the forward part of the ship since the action began but, considering the large number of hits we had felt, there must have been some drastic changes. Suddenly I heard Albrecht’s voice on the control telephone. “The forward fire-control station has to be evacuated because of gas and smoke,” he said, and immediately rang off, precluding any questions. I was surprised. I had assumed that the reason for the fire control being turned over to me was that the forward station was out of action. Had Albrecht been directing the secondary battery from there? Was his own station serving only as a place of refuge? I would not learn the answers to those questions until many years later.

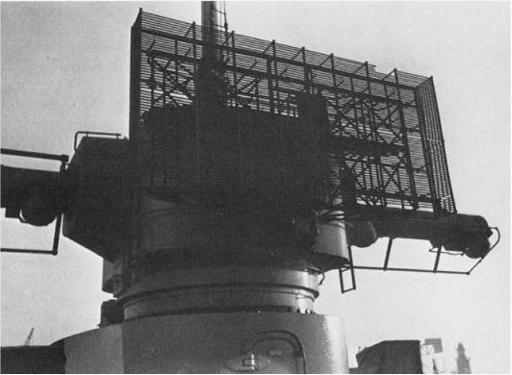

This exterior view of the

Bismarck’s

after fire-control station shows the optical range finder in its revolving cupola. Its lenses are pointing downward and have protective covers in place. Attached to the front of the cupola is a “mattress” radar antenna. To the left and behind the cupola base is the lens housing for one of the two directors in this station. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

I was using all the telephone circuits and calling all over the place

in an effort to find out as much as possible about the condition of the ship. I got only one answer. I reached the messenger in the damage-control center, and asked: “Who has and where is the command of the ship? Are there new orders in effect?” The man was in a great hurry and said only that both the First Officer and the Damage-Control Engineer had had to abandon the damage-control center, adding that he was the last one in the room and had to get out. Then he hung up. That was my last contact with the forward part of the ship.

Salvos falling near the

Bismarck

during her final action with the Home Fleet. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

Before 1000, men who had had to abandon their own stations or protected rooms began arriving to take refuge in my station. Most of them came through the narrow emergency exit where a perpendicular companionway led down to the after gunnery reserve circuit space. They clambered up its iron rungs, the uninjured, the slightly wounded, and many so badly wounded that one could only marvel that they did it. We were lucky that my station was not hit. While heavy firing was still going on, I had the two small exit hatches carefully cranked open. I believed—and convinced the men—that it was better to take a chance on a few splinters than risk having the opening mechanism jammed by a hit. In fact, we were spared both shell splinters and fragments.

Around this time, the order was given to scuttle and abandon the ship, although I did not know it then. In fact, no such order ever reached me, but the situation on board compelled me to conclude

that it must have been given. Nevertheless, I did not allow the men in my station to leave while shells were exploding all over the superstructure and main decks, and ready ammunition was blowing up. To do so would have been nothing less than suicide. I did not give the order to leave until long after our guns had fallen silent, the enemy stopped firing and, presumably, the shooting had come to an end.

By this time our list to port was heavier than ever and starboard was the lee side. I called to the men to look for a place aft and to starboard on the main deck. Forward, there was too much destruction and the smoke was unbearable. The quarterdeck was out of the question: the sinking ship was too far down by her stern and heavy breakers were rolling over her from her port quarter. Those who made the mistake of jumping from that side or who were washed overboard in that direction were thrown hack against the ship by the sea, in most cases with fatal consequences.

The last one to leave the station, I went forward, towards the searchlight-control station or, rather, towards where it had been. The scene that lay before me was too much to take in at a glance and is very difficult to describe. It was chaos and desolation. The antiaircraft guns and searchlights that once surrounded the after station had disappeared without a trace. Where there had been guns, shields, and instruments, there was empty space. The superstructure decks were littered with scrap metal. There were holes in the stack, but it was still standing. Whitish smoke, like a ground fog, extended from the after fire-control station all the way to the tower mast, indicating where fires must be raging below. It obscured anything that was left on the superstructure. Out of the smoke rose the tower mast, seemingly undamaged. How good it looks in its gray paint, I thought, almost as if it had not been in the battle. The foretop and the upper antiaircraft station also looked intact, but I well knew that such was not the case. Men were running around up there—I wondered whether they would be able to save themselves, to find a way down inside the mast. The wreckage all around made it impossible for me to go any farther forward and I returned to my station, only to leave it again immediately and go aft. I had to clamber over all manner of debris and jump over holes in the deck. I saw the body of a fleet staff officer, lying there peacefully, without any sign of injury. He must have left his action station when the order was given to abandon ship, without waiting for the enemy fire to cease. Turret Caesar, its barrels at high elevation and trained towards our port bow, was apparently undamaged. The light, shining gray of its paint contrasted oddly with

the surrounding devastation. Its commander, Leutnant zur See Günter Brückner, was forced to stop firing when his left gun barrel was disabled. Then Brückner directed the following words to his turret crew: “Comrades, we’ve loved life; now, if nothing changes, we’ll die like good seamen,” and ordered them to abandon the turret. From the upper deck I saw turret Dora, blackened by smoke, trained port side forward. A shell burst had shredded its right barrel, but the gun captain, Oberbootsmannsmaat Friedrich Helms, had still fired two shots from the left barrel. Then Mechanikersmaat Ernst Moog had climbed up from the interior of the turret, shouting that turret Dora was burning, and the whole crew, still uninjured, had to abandon it, so the turret fell completely silent. Later still a shell detonated, probably on the battery deck, and hurled the hatch to the munitions chamber high into the air. Helms and others suffered burns to their faces and hands through the jets of flame that shot up.

Moving on, I glanced across the water off our starboard quarter, and couldn’t believe what I saw. There, only around 2,500 meters away, was the

Rodney

, her nine guns still pointing mistrustfully at us. I could look down their muzzles. If that was her range at the end of the battle, I thought, not a single round could have missed. But her guns were silent now and I didn’t expect that they would go into action again.

The

King George V

and the

Rodney

had steered towards the scene of the coming battle on course 110° at a speed of 19 knots in line-abreast formation with a distance of 1,200 meters between them, the

Rodney

to port of the

King George V

. The

Rodney

had not attained her design speed of 22 knots for several years, but during the last three days she had nevertheless averaged between 20 and 21 knots. Through the consequent vibration she had lost some of the rivets in her hull, with the result that fuel oil was leaking into the sea and leaving a thin coating in her wake as far as the eye could see. At 0843 the sharp gray silhouette of the

Bismarck

, making an estimated 10 knots, appeared out of a dark rain squall 250 hectometers to the southeast and the

Rodney’s

Captain F. H. G. Dalrymple-Hamilton, a man of few words, spoke only five to his crew: “Going in now—good luck!” Then the

Rodney

had opened fire, followed a minute later by the

King George V

. Another minute thereafter the

Bismarck

had replied.

In the

Rodney

men realized that they were facing a German battleship which, while incapable of maneuvering, had all her guns fully intact and a gunnery officer who was probably hoping quickly to

eliminate the heavy batteries mounted exclusively on the foreship of his principal opponent and therefore dangerously exposed by this bows-on approach to the

Bismarck

, and perhaps to need only a few salvos to do so, as against the

Hood

three days ago. For must not Schneider, well aware of the frightful penetrating power of the Rodney’s more than two thousand-pound shells, force a quick decision in order to survive? But he could attain such a success only if, despite the

Rodney’s

extremely small silhouette in the opening stage of the action, his observations enabled him to find his target right away.

To continue, in the words of an observer in the

Rodney:

“From about 0936 until cease firing at 1016 the

Rodney

steamed back and forth by the

Bismarck

at ranges between 2750 and about 4500 yards firing salvo after salvo of 16″ and 6″ during this entire period.” The trajectories of the shells were nearly flat and the devastation of the

Bismarck

was readily visible to her enemies. Several fires were raging and the back of turret Bruno was missing. The superstructure had been destroyed, men were running back and forth on deck, vainly seeking shelter, their only escape from the hail of fire being over the side.

Around 1000 the

Bismarck

appeared to the British to be a wreck. Her gun barrels pointed every which way into the sky, and the wind drew black smoke out of her interior. The glow of fires on her lower decks shone through the holes in her main deck and upper citadel armor belt.

To Tovey it appeared almost incredible that the

Bismarck

was still afloat. The knowledge that German long-range bombers or German U-boats might appear at any moment made the urgency of sinking her ever more pressing. Moreover, his flagship and the

Rodney

were running alarmingly low on fuel. Repeatedly he urged Patterson, “Get closer, get closer—I can’t see enough hits.” In order to hasten the end of the

Bismarck

, the

Rodney

fired three full salvos with her 40.6-centimeter battery at full depression, scoring three or four hits per salvo. At a range of 2,700 meters, she released her last two torpedoes and the

Norfolk

, at a range of 3,600 meters, fired her last four torpedoes—the

Bismarck

remained afloat.