Beautiful Ruins

Beautiful Ruins

A Novel

Jess Walter

The ancient Romans built their greatest

masterpieces of architecture for wild beasts to fight in.

—Voltaire,

The Complete Letters

Cleopatra: I will not have love as my master.

Marc Antony: Then you will not have love.

—from the 1963 disaster film

Cleopatra

[Dick] Cavett’s four great interviews with Richard Burton

were done in 1980. . . . Burton, fifty-four at the time, and

already a beautiful ruin, was mesmerizing.

—

“Talk Story” by Louis Menand,

The New Yorker,

November 22, 2010

Contents

The Dying Actress

April 1962

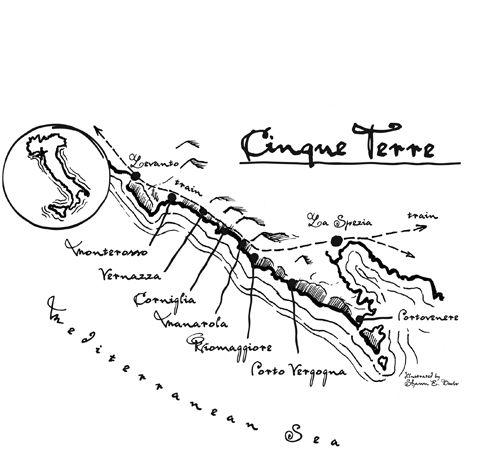

Porto Vergogna, Italy

T

he dying actress arrived in his village the only way one could come directly—in a boat that motored into the cove, lurched past the rock jetty, and bumped against the end of the pier. She wavered a moment in the boat’s stern, then extended a slender hand to grip the mahogany railing; with the other, she pressed a wide-brimmed hat against her head. All around her, shards of sunlight broke on the flickering waves.

Twenty meters away, Pasquale Tursi watched the arrival of the woman as if in a dream. Or rather, he would think later, a dream’s opposite: a burst of clarity after a lifetime of sleep. Pasquale straightened and stopped what he was doing, what he was usually doing that spring, trying to construct a beach below his family’s empty

pensione

. Chest-deep in the cold Ligurian Sea, Pasquale was tossing rocks the size of cats in an attempt to fortify the breakwater, to keep the waves from hauling away his little mound of construction sand. Pasquale’s “beach” was only as wide as two fishing boats, and the ground beneath his dusting of sand was scalloped rock, but it was the closest thing to a flat piece of shoreline in the entire village: a rumor of a town that had ironically—or perhaps hopefully—been designated

Porto

despite the fact that the only boats to come in and out regularly belonged to the village’s handful of sardine and anchovy fishermen. The rest of the name,

Vergogna

, meant shame, and was a remnant from the founding of the village in the seventeenth century as a place for sailors and fishers to find women of . . . a certain moral and commercial flexibility.

On the day he first saw the lovely American, Pasquale was chest-deep in daydreams as well, imagining grubby little Porto Vergogna as an emergent resort town, and himself as a sophisticated businessman of the 1960s, a man of infinite possibility at the dawn of a glorious modernity. Everywhere he saw signs of

il boom

—the surge in wealth and literacy that was transforming Italy. Why not here? He’d recently come home from four years in bustling Florence, returning to the tiny backward village of his youth imagining that he brought vital news of the world out there—a glittering era of shiny

macchine

, of televisions and telephones, of double martinis and women in slender pants, of the kind of world that had seemed to exist before only in the cinema.

Porto Vergogna was a tight cluster of a dozen old whitewashed houses, an abandoned chapel, and the town’s only commercial interest—the tiny hotel and café owned by Pasquale’s family—all huddled like a herd of sleeping goats in a crease in the sheer cliffs. Behind the village, the rocks rose six hundred feet to a wall of black, striated mountains. Below it, the sea settled in a rocky, shrimp-curled cove, from which the fishermen put in and out every day. Isolated by the cliffs behind and the sea in front, the village had never been accessible by car or cart, and so the streets, such as they were, consisted of a few narrow pathways between the houses—brick-lined roads skinnier than sidewalks, plunging alleys and rising staircases so narrow that unless one was standing in the piazza San Pietro, the little town square, it was possible anywhere in the village to reach out and touch walls on either side.

In this way, remote Porto Vergogna was not so different from the quaint cliff-side towns of the Cinque Terre to the north, except that it was smaller, more remote, and not as picturesque. In fact, the hoteliers and restaurateurs to the north had their own pet name for the tiny village pinched into the vertical cliff seam:

baldracca culo

—the whore’s crack. Yet despite his neighbors’ disdain, Pasquale had come to believe, as his father had, that Porto Vergogna could someday flourish like the rest of the Levante, the coastline south of Genoa that included the Cinque Terre, or even the larger tourist cities on the Ponente—Portofino and the sophisticated Italian Riviera. The rare foreign tourists who boated or hiked into Porto Vergogna tended to be lost French or Swiss, but Pasquale held out hope the 1960s would bring a flood of Americans, led by the

bravissimo

U.S. president, John Kennedy, and his wife, Jacqueline. And yet, if his village had any chance of becoming the

destinazione turistica primaria

he dreamed of, Pasquale knew it would need to attract such vacationers, and to do that, it would need—first of all—a beach.

And so Pasquale stood half-submerged, holding a big rock beneath his chin as the red mahogany boat bobbed into his cove. His old friend Orenzio was piloting it for the wealthy vintner and hotelier Gualfredo, who ran the tourism south of Genoa but whose fancy ten-meter sport boat rarely came to Porto Vergogna. Pasquale watched the boat settle in its chop, and could think of nothing to do but call out, “Orenzio!” His friend was confused by the greeting; they had been friends since they were twelve, but they were not yellers, he and Pasquale, more . . . acknowledgers, lip-raisers, eyebrow-tippers. Orenzio nodded back grimly. He was serious when he had tourists in his boat, especially Americans. “They are serious people, Americans,” Orenzio had explained to Pasquale once. “Even more suspicious than Germans. If you smile too much, Americans assume you’re stealing from them.” Today Orenzio was especially dour-faced, shooting a glance toward the woman in the back of his boat, her long tan coat pulled tight around her thin waist, her floppy hat covering most of her face.

Then the woman said something quietly to Orenzio, and it carried across the water. Gibberish, Pasquale thought at first, until he recognized it as English—American, in fact: “Pardon me, what is that man doing?”

Pasquale knew his friend was insecure about his limited English and tended to answer questions in that awful language as tersely as possible. Orenzio glanced over at Pasquale, holding a big rock for the breakwater he was building, and attempted the English word for

spiaggia

—beach—saying with a hint of impatience: “Bitch.” The woman cocked her head as if she hadn’t heard right. Pasquale tried to help, muttering that the bitch was for the tourists,

“per i turisti.”

But the beautiful American didn’t seem to hear.

It was an inheritance from his father, Pasquale’s dream of tourism. Carlo Tursi had spent the last decade of his life trying to get the five larger villages of the Cinque Terre to accept Porto Vergogna as the sixth in the string. (“How much nicer,” he used to say, “

Sei Terre

, the six lands. Cinque Terre is so hard on tourists’ tongues.”) But tiny Porto Vergogna lacked the charm and political pull of its five larger neighbors. So while the five were connected by telephone lines and eventually by a tunneled rail line and swelled with seasonal tourists and their money, the sixth atrophied like an extra finger. Carlo’s other fruitless ambition had been to get those vital rail lines tunneled another kilometer, to link Porto Vergogna to the larger cliff-side towns. But this never happened, and since the nearest road cut behind the terraced vineyards that backed the Cinque Terre cliffs, Porto Vergogna remained cut off, alone in its wrinkle in the black, ribbed rocks, only the sea in front and steep foot-trails descending the cliffs behind.

On the day the luminous American arrived, Pasquale’s father had been dead for eight months. Carlo’s passing had been quick and quiet, a vessel bursting in his brain while he read one of his beloved newspapers. Over and over Pasquale replayed his father’s last ten minutes: he sipped an espresso, dragged a cigarette, laughed at an item in the Milan newspaper (Pasquale’s mother saved the page but never found anything funny in it), and then slumped forward as if he were napping. Pasquale was at the University of Florence when he got news of his father’s death. After the funeral, he begged his elderly mother to move to Florence, but the very idea scandalized her. “What kind of wife would I be if I left your father simply because he is dead?” It left no question—at least in Pasquale’s mind—that he must come home and care for his frail mother.

So Pasquale moved back into his old room in the hotel. And perhaps it was guilt over having dismissed his father’s ideas when he was younger, but Pasquale could suddenly see it—his family’s small inn—through newly inherited eyes. Yes, this town could become a new kind of Italian resort—an American getaway, parasols on the rocky shore, camera shutters snapping, Kennedys everywhere! And if there was a measure of self-interest in turning the empty

pensione

into a world-class resort, so be it: the old hotel was his only inheritance, the sole familial advantage in a culture that required it.

The hotel was comprised of a

trattoria

—a three-table café—a kitchen and two small apartments on the first floor, and the six rooms of the old brothel above it. With the hotel came the responsibility of caring for its only regular tenants,

le due streghe

, as the fishermen called them, the two witches: Pasquale’s crippled mother, Antonia, and her wire-haired sister, Valeria, the ogre who did most of the cooking when she wasn’t yelling at the lazy fishermen and the rare guest who stumbled in.

Pasquale was nothing if not tolerant, and he abided the eccentricities of his melodramatic

mamma

and his crazy

zia

just as he put up with the crude fishermen—each morning skidding their

peschereccio

down to the shoreline and pushing out into the sea, the small wooden shells rocking on the waves like dirty salad bowls, thrumming with the

bup-bup

of their smoking outboards. Each day the fishermen netted just enough anchovies, sardines, and sea bass to sell to the markets and restaurants to the south, before coming back to drink grappa and smoke the bitter cigarettes they rolled themselves. His father had always taken great pains to separate himself and his son—descendants, Carlo claimed, of an esteemed Florentine merchant class—from these coarse fishermen. “Look at them,” he would say to Pasquale from behind one of the many newspapers that arrived weekly on the mail boat. “In a more civilized time, they would have been our servants.”

Having lost two older sons in the war, Carlo wasn’t about to let his youngest son work on the fishing boats, or in the canneries in La Spezia, or in the terraced vineyards, or in the marble quarries in the Apennines, or anywhere else a young man might learn some valuable skill and shake the feeling that he was soft and out of place in the hard world. Instead, Carlo and Antonia—already forty when Pasquale was born—raised Pasquale like a secret between them, and it was only after some pleading that his aging parents had even allowed him to go to university in Florence.

When Pasquale returned after his father’s death, the fishermen were unsure what to think of him. At first, they attributed his strange behavior—always reading, talking to himself, measuring things, dumping bags of construction sand on the rocks and raking it like a vain man combing his last wisps of hair—to grief. They strung their nets and they watched the slender twenty-one-year-old rearrange rocks in hopes of keeping storms from hauling away his beach, and their eyes dewed over with memories of the empty dreams of their own dead fathers. But soon the fishermen began to miss the good-natured ribbing they’d always given Carlo Tursi.

Finally, after watching Pasquale work on his beach for a few weeks, the fishermen could stand it no longer. One day, Tomasso the Elder tossed the young man a matchbox and called out, “Here’s a chair for your tiny beach, Pasquale!” After weeks of unnatural kindness, the gentle mockery was a relief, the bursting of storm clouds above the village. Life was back to normal. “Pasquale, I saw part of your beach yesterday at Lerici. Shall I take the rest of the sand up there or will you wait for the current to deliver it?”

But a beach was something the fishermen could at least understand; after all, there were beaches in Monterosso al Mare and in the Riviera towns to the north, where the town’s fishermen sold the bulk of their catches. When Pasquale announced his intention to carve a tennis court into a cluster of boulders in the cliffs, however, the fishermen declared Pasquale even more unhinged than his father. “The boy has lost his sense,” they said from the small piazza as they hand-rolled cigarettes and watched Pasquale scamper over the boulders marking the boundaries of his future tennis court with string. “It’s a family of

pazzi

. Soon he’ll be talking to cats.” With nothing but steep cliff faces to work with, Pasquale knew that a golf course was out of the question. But there was a natural shelf of three boulders near his hotel, and if he could level the tops and cantilever the rest, he thought he could build forms and pour enough concrete to connect the boulders into a flat rectangle and create—like a vision rising out of the rocky cliffs—a tennis court, announcing to visitors arriving by sea that they had come upon a first-class resort. He could close his eyes and see it: men in clean white pants lobbing balls back and forth on a stunning court projecting out from the cliffs, a glorious shelf twenty meters above the shoreline, women in dresses and summer hats sipping drinks beneath nearby parasols. So he chipped away with a pick and chisels and hammers, hoping to prepare a large enough space for a tennis court. He raked his dusting of sand. He tossed rocks in the sea. He endured the teasing of the fishermen. He peeked in on his dying mother. And he waited—as he always had—for life to come and find him.