Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (142 page)

Â

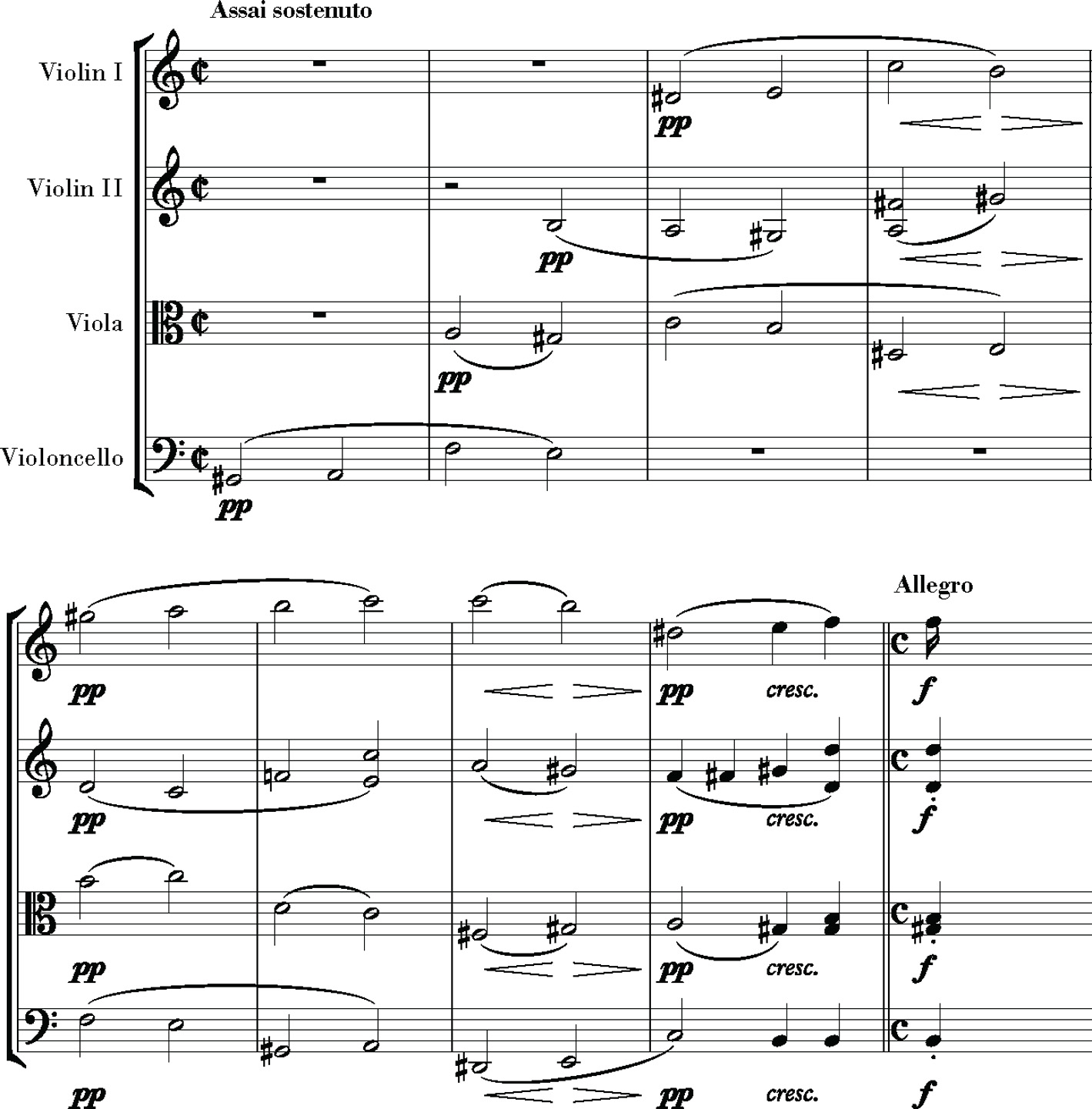

Before the first theme proper, those six introductory bars embody another of Beethoven's games of these years with familiar formal functions: is this opening a theme or a micro-introduction? In practice it is more or less the latter, but it turns up a couple of times further in the movement, so it might better be called some sort of motto passage. The significant melodic element is the violin's rise of a sixth from E-flat to a trilled C in bar six. That sixth is going to be the compass of most themes to come, and C is going to be the main tonality of the development section. The first theme appears, warm and flowing, in the violin line, handed off to viola, with a fine lyrical charm. The rich contrapuntal web of these bars is going to return in various guises and permutations some two dozen times.

51

In a compact exposition, the G-minor second theme flows lyrically like the first, and soon makes its way back to the first-theme idea. After a brief closing section we find ourselves returned to the opening “introduction,” as if the exposition has made the usual repeat back to the beginning. But the introductory idea is now in G major, and it ushers in the development without a repeat of the exposition. The development slips almost imperceptibly back into a transformed recapitulation, as if the recap were a continuation of the development. The coda, almost as long as the other sections, is pensive, to prepare the slow movement.

Â

Â

At one point in composing op. 127, Beethoven thought the quartet might have six movements, one of them called

La Gaieté

âas if in response to

La Malinconia

in op. 18. That plan receded to four movements, and the lively

Gaieté

theme metamorphosed into the theme of the Adagio.

52

That movement begins with a long, slow-arching theme as subject for five gently beautiful variations. Here Beethoven's intensified focus on part writing comes to the front of the stage: unlike anything before, these verge on

texture variations

, some of those textures made of several distinct figures in the instruments:

Â

Â

The fourth variation is an endless melody in the first violin, accompanied by pulsing chords. In the last variation the violin leads the way into a liquid texture of sextuplets. While the first movement was just over six and a half minutes, the variations are some sixteen and a half. The next two movements will each be just under seven minutes, so the slow movement is nearly as long as the other three combined.

The third movement is another of his sui generis outings. Marked Scherzando vivace, lively and playful, it is therefore a scherzo, and in scherzoâtrioâscherzo form. Otherwise it sounds nothing like a scherzo, or a minuet either, though it is in 3/4 and in minuet rather than scherzo tempo. All of it is based on a bouncing and ironic tune that goes in and out of fugue, like a parody of a fugue extended to the point of seeming endless. The trio comes on in breathless triple one-beat, like a manic scherzo. Here are the kind of instant changes of direction that marked the late piano sonatas and some of the

Missa solemnis

, now introduced to the string quartet.

In the finale, after another short, sort-of introduction (which characterizes the beginning of all the movements), the first theme of the sonata form is again warmly lyrical, like most of the quartet, and manifestly derived from the first theme of the first movement:

Â

Â

Here lines in long, flowing phrases alternate with dancing figures in delicate staccato, especially the second theme. As in the first movement, a compact exposition slips without repeat into a compact development that continues unbroken into a highly varied developmental recapitulation and finally into a long coda.

53

There is something magical about this coda, which transforms the main theme into passages that recall the liquid last variation of the slow movement. It ends with the kind of heart-filling affability that has marked the quartet from the beginning.

In its innovations, the wonderfully fresh and engaging op. 127 picks up a little down the road from the two quartets of a decade beforeâthe

Serioso

and the

Harp

. Then in the

Galitzins

the serious deconstruction of forms and norms began.

Â

Another mark of Beethoven's late music is the union of mystery and surprise, even shock, with an inner logic that sinks traditional structure deeper beneath the fantasy-like surface. The quiet opening of the A Minor String Quartet, op. 132, presents us with an effect of a gnomic puzzle continually turning around on itself:

Â

Â

The four-note motive that is turned over and aroundâa half step up, a leap (primally a sixth) up and a half step downâis the fundamental motive of the quartet, both as intervals and as shape: step upâleapâstep down. It will seed every theme, in ways both overt and subtle:

Â

Â

At the same time the opening implies most of the tonal centers in the quartet: the first four notes outline A minor, the first notes in the violin hint at E minor and then C major. The FâE of the second bar is another primal motif; here it foreshadows, among other things, the F major of the second theme. The opening phrase, in other words, virtually contains the quartet in embryo, including the austere contrapuntal texture that will flower in the third movement.

The tone of the first movement is peculiarly poignant; call it poised between yearning and hope. A minor was an unusual key for Beethoven. This quartet defines it not as a tragic tonality but rather as a key of Romantic passion, irony, and mystery. Call it a distant descendant, in another country, of an earlier rhapsodic work in A minorâthe

Kreutzer

Sonata.

After the opening bars turning around the motto, there is a sudden skittering Allegro that as suddenly dissolves. Fragments of a breathless, yearning theme burst out, alternating with driving dotted descents on a B-flat triad. That phrase, constantly shifting among the instruments, is less a theme than a theme about a theme, or a gesture toward a theme that remains in potential. Yearning for the unrealizable: this is Romantic territory.

In its incompleteness the yearning phrase is nonetheless the main material of the movement, with new continuations in endless development. The rest of the matter is the skittering Allegro idea, the driving dotted figures, and a sweetly aching second theme in F major. These leaps among contrasting ideas, from quiet and austere to loud and passionate, foreshadow events all the way to the dichotomies of the third movement. There are no transitions, only sudden juxtapositions, like a character who is prey to manic emotions in a Sturm und Drang tale.

We are nominally in sonata form, though there is no repeat of the exposition, and the recapitulation apparently starts in the wrong key (E minor); a page later the music slips back into the proper A minor, but only briefly. From early on, Beethoven looked for fresh harmonic relationships within sonata form, turning away from the usual second theme in the dominant key to ones in mediants (III and VI), which became his norm. This fresh treatment of keys happened in the middle period, while his handling of formal outlines remained relatively traditional. Now, to say what he needs to say he has to bend the old forms a great deal more, to more radical ends. Here, as in the E-flat Quartet but more thoroughly, he often departs from clear and regular Classical phrasing; he writes more than the usual four movements; he suppresses and rearranges familiar formal and tonal landmarks for a through-composed effect; he makes the recapitulation nearly as developmental as the development section.

54

In the A Minor the transformation of ideas is so constant from the beginning that it questions the very meaning of “exposition”: when we first hear the yearning theme it enters the scene breathlessly, in fragments, as if it were already a recollection, a passionate wisp of memory known to the character onstage but not to us.

The second-movement scherzo is an ineffably zany interlude. It begins with rising figures based on the first movement's motto; over that phrase Beethoven places a swirling little waltz tune. This contrapuntal pair simply refuses to leave, dancing on chirpily through changes of key and texture in a display of Beethovenian minimalism. The middle-section trio is another instant shift of gears, its theme an ethereal musette.

In the third movement, like one of E. T. A. Hoffmann's imaginary authors who breaks into his own fiction, the composer steps from behind the curtain and reveals what this movement's bifurcating directions are about. It is labeled on the score

Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart

, “Holy song of thanks to God from a convalescent, in Lydian mode.” The joyful dance that twice interrupts the hymn is headed

Neue Kraft fühlend

, “Feeling new strength.” The convalescent is, of course, Beethoven himself, recovered from a dangerous illness. Here too is Romantic territory: the artist as subject of his art.