Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (146 page)

Â

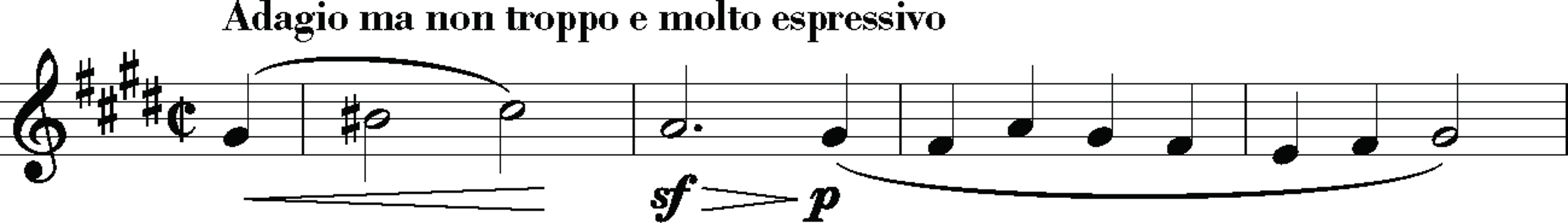

The C-sharp Minor Quartet, op. 131, begins with a keening melody on the middle strings of the violinâits most subdued register, in a shadowed key. The movement is headed Adagio ma non troppo, e molto espressivo. A second violin enters with the theme; a fugue begins to take shape. As the entries work their way down to the cello the texture remains austere, moving in simple quarter and half notes. The spareness and simplicity recall the

Heiliger Dankgesang

of the A Minor Quartet, but that was a hymn of thanks and this is a song of mourning. Both have an archaic feel, this one like a Renaissance ricercar.

29

Long before, Beethoven had begun to invest the old genre of fugue with more emotion than it had ever possessed.

30

Here is the climax of that investment. Richard Wagner was to say that he found this movement “the saddest thing ever said in notes.” It is as if this music expressed the distillation of a minor key and its intrinsic sorrow, in the same way that the finale of the op. 111 Piano Sonata expresses some distillation of C major.

The singularity of this opening has to do with its being Beethoven's only first-movement fugue, and one of distinctive cast. Part of the effect is the rarity of its key. To find his only other work in C-sharp minor, and his last opening on a slow movement, one looks back to the

Moonlight

Sonata of 1801, with its haunting first movement. But C-sharp minor in piano and in strings are quite different matters. Its effect on keyboard has to do, if anything, with tunings in unequal temperament. In strings, the key is distinctively shadowed because it involves so few open stringsâonly A and E, the mediants of the scale. Partly for that reason, Beethoven picks out those notes and those keys in the quartet and begins a variation with them in the slow movement.

31

The piece did not come easily. There were more than six hundred pages of sketches that included five sets of plans for the movements.

32

As it finally took shape, the quartet comprised seven numbered movements, each rising from the preceding one with little or no pause. He did not write the usual ending double bar until the conclusion of the piece. The whole is grounded on the beginning, the bare fugue theme that constitutes the

Thema

. The first three notes, G-sharpâB-sharpâC-sharp, form a head motif that will resonate all the way to the finale. The next two bars are the tail motif, whose scalewise flow will also have a long career. The first part of the

Thema

points to sorrow, the gently flowing last part to resignation and hope:

Â

Â

No less important is a single note invested with enormous consequence, the accented open-string A on the downbeat of the second bar. It sets up the importance of A major through the quartetâalso D major, D being the accented note in the second violin's answer. In the opening bars, the A and the D are both heartrending.

33

The second entry of the subject is not on the usual dominant key, G-sharp, but on F-sharp minor, the subdominant and the relative minor of A major. F-sharp minor will be another important key in the first movement, and at the end of the quartet F-sharp and C-sharp will still be contending.

34

The keys of the whole will be as unified as if they were a single movement. Most Classical works, including most by Beethoven, have two or at most three keys in their movements. The B-flat Major has four keys; the C-sharp Minor has six.

No fugal movements in late Beethoven are pure fugues. Each of them is a unique integration of Baroque and Classical models. The first movement of the C-sharp Minor begins with a full fugal exposition, but much of the rest is a contrapuntal and imitative development on the motifs of the theme, sonata-like, including a second-theme-like section in B major (not fugal) where the tail motif is diminished into eighth notes. After some exquisitely poignant echoing duets and more development, the last section before the coda is a fugue using an augmentation of the theme, each note doubled in length. The first clear cadence to C-sharp minor does not arrive until the end of the movement; the first truly firm cadence to that key is in the finale. The ending of the first movement, rich with double-stops, turns to C-sharp major, like one of Bach's lush conclusions. (Beethoven's fugue and its mood have a close affinity to the one in that key in

The Well-Tempered Clavier

.)

35

Just before the final bars, the first violin reaches up achingly to D-natural, the gesture enfolding both feeling and logic: it makes a tonal transition to the second movement's nimble and dashing 6/8 gigue in D major, marked Allegro molto vivace. Deep darkness to light: part of the effect of the second movement's sudden brightening is the effect of D major in the instruments, that key ringing most of the open strings. Like all the movements, the second has a memorable leading theme, blithe and liquid. The movement is short and nominally in sonata form, though there is little trace of a development section. A big coda builds up to a stern, three-octave declamation that resurrects the serious side of the quartet. The sound remains open and simple; this quartet will not engage in the kinds of textural experiments Beethoven did in the

Galitzins

.

The coda of the second movement slips suddenly from

fortissimo

to soft sighs and fragments. What comes next is marked “No. 3,” as if it were a movement, but really it is a short preface to the next movementâ“preface” rather than “transition,” because it amounts to brief skipping gestures and a sudden passionate burst of quasi-cadenza and quasi-recitative, each lasting a few seconds.

The central movement is marked Andante ma non troppo e molto cantabile, the last meaning “very songful.” It is variations on a memorable and ingenuous tune that is presented in call-and-response between the violins. All is simple and transparent, the harmony placid, the rhythm gently striding, the focus on the tune but with melodic undercurrents in the accompaniment. The theme flows into the first variation, and all are linked. The variations contrast, but gently: the first flowery and contrapuntal, the second marchlike, and so on. The end of the movement is a train of vignettes: cadenzas for each of the instruments; a brief and breathless recollection of the theme in the wrong key (C major); a flowery, inexplicable processional full of trills that suddenly vanishes; another breathless recall of the opening theme; a zipping violin cadenza; for coda, fragmentary echoes of the theme.

Next is the scherzo proper, Presto in 2/2, in E major and with a trio in the middle. Here is comedy in rumbustious staccato, the tone somewhere between folklike and childlike, starting with the cello's gruff opening gesture like a clearing of the throat. This movement is as tuneful as the others, especially the lyrical musette-like theme of the trio, which has a giddy refrain that is one of Beethoven's most childlike, if not childish, moments. After a triple repeat of the scherzo, a double repeat of the trio, and a feint at a third repeat of the trio, the coda begins with the main theme returning in a remarkable guise: marked

sul ponticello

, an effect of playing next to the bridge of the instrument that produces a ghostly, metallic, from-afar quality. (Where had Beethoven heard this then-almost-unknown effect?)

36

The

ponticello

phrase is the perfect conclusion for a wonderfully wry movement.

Just as “movement” no. 3 was not really a movement but a preface for no. 4, no. 6 is a preface for no. 7, in the form of a somber, aria-like Adagio in G-sharp minor. Though it lasts a minute and a half, it amounts to yet another fragment. Its key of G-sharp minor prepares the C-sharp-minor finaleâthe first time that key has returned anywhere since the first movementâand its tone returns us to the seriousness, though not the sorrow, of the first movement. In effect it poses a question: at the end of this journey that started in tragedy and takes us through dance and grace and tenderness and laughter and nursery tunes, where do we end?

We end in a fierce march, the first movement in the quartet to have a fully decked-out sonata form. Its main theme sits on a C-sharp-minor chord for its first six bars, a definitive grounding on the tonic chord that the first movement never reached. From there the finale is broadly integrative, pulling together ideas from the whole. Here again is the D-natural whose interjection into the quartet's opening fugue contributed to that movement's feeling of sorrow. The finale theme's legato second section, too, returns to the head motif of the first fugue, first inverted and then right-side up:

Â

Â

A short but warmly lyrical second theme breaks out in a bright, breathtaking E major, its rising line recalling the trio theme of the scherzo, its resonant fifths in the cello recalling the end of the first movement and the fifth variation of the third movement. The driving staccato of the march recalls the staccato scherzo and the second variation of the second movement. The keys are the leading ones of the quartet: E and D major, F-sharp minor in the coda. The end barely makes it out of F-sharp minor to a quick, full-throated close on C-sharp major.

The earlier B-flat Major Quartet was the distillation of Beethoven's Poetic style: mercurial, fantasia-like, unpredictable from moment to moment in its mingling of light and dark. The C-sharp Minor is an integration of the Poetic style with the organic quality of his earlier music. Each movement is tightly made, with one or two leading ideas and contrasts subdued (except in the variations). The textures are simple and open, which is to say Classical. The movements flow together with little or no break between. The contrasts, deep ones, are mainly between rather than within the movements. There is no single dramatic unfolding but rather a mingling of qualities, as if the whole quartet were one variegated movementâand this is surely one of the reasons Beethoven called this his best quartet. Much of the overall effect has to do with the sound of its keys on the instruments: the darkness of C-sharp minor, F-sharp minor, and G-sharp minor with few open strings, while the other keys are the brightest ones on the instruments, resonating with open strings: A, D, E.

37

As an answer to the suffering of the first movement, the finale is driving and dynamic but not heroic, not with the kind of triumph that ended the Third and Fifth and Ninth Symphonies,

Fidelio

, and

Egmont

. The overcoming of sorrow here is more subtle, shaded, hard won. Schiller wrote that in art suffering must be answered by a heroic overcoming, as an act of free moral will: “The depiction of suffering, in the shape of simple suffering, is never the end of art, but it is of the greatest importance as a means of attaining its end . . . This is effected in particular by tragic art, because it represents . . . the moral man, maintaining himself in a state of passion, independently of the laws of nature. The principle of freedom in man becomes conscious of itself only by the resistance it offers to the violence of the feelings.”

38

In his music Beethoven had largely treated tragedy in those terms. The heroic Fifth and the Ninth begin in darkness and end in triumph. (An exception is the

Appassionata

Sonata, where tragedy has the last word.) In the C-sharp Minor Quartet, the transcendence is deeper. In the first movement the formality of the fugal idea makes it something on the order of a ceremony carried out within the most profound grief. Transcendence is adumbrated in the moments of hope that temper the first movement, in the integral fabric that enfolds the whole quartet, in its emotional journey that enfolds so much of life. It is not a one-directional journey like that of the Fifth Symphony. Here light and shadow, comedy and tragedy, innocence and experience mingle as they do in life, as they mingled in Beethoven's own mercurial sensibility. The triumph in the C-sharp Minor Quartet is not in heroic gestures or in the kind of wild joy that ended

Fidelio

and the

Eroica

. As Beethoven's increasingly hard-won labors transcended the anguish of his life, the triumph of the C-sharp Minor Quartet, its answer to suffering, is the supreme poise and integration of the whole work.