BELGRADE (10 page)

Authors: David Norris

Miloš Obrenović was a shrewd ruler whose political ambitions were largely determined by his personal fortune. With Russian support, he won further concessions from the Ottoman Empire enshrined in the

hattisherif

, or sultan’s edict, of 1830. At a solemn meeting on Tašmajdan this decree was read out to the Serbian leadership. It promised them religious freedom, greater political control over their own affairs and sundry new rights such as their own postal service. It was announced that the Ottoman administration would not interfere in their internal affairs, the territory under Serbian control was enlarged, and Miloš was made hereditary knez. Foreign powers opened consular posts in Belgrade and soon an embryonic diplomatic presence was established with representatives from France, Austria, Russia and an Englishman, Colonel Hodges. But the new settlement also restricted the ruler’s personal power by introducing a council to rule alongside him. This new arrangement did not suit Miloš’s autocratic temperament, or his immediate aims. His main opponent was Toma Vučić Perišić, leader of a group calling itself the Constitutionalists who wanted to curb Miloš’s dictatorial style of government in order to increase their own share of power. For reasons of their own, members of Miloš’s family, his wife, Kneginja Ljubica, and his brother, Gospodar Jevrem, lent their support to the conspiracy. The knez was obliged to accept further limits on his activities until he was finally forced to abdicate in 1839 when he went into exile. He was succeeded by his son Milan, a sickly boy who soon died and who was in turn succeeded by his sixteen-year–old brother Mihailo. Vučić Perišić knew that he was not going to realize his personal ambitions while the Obrenović family remained in Belgrade, so he also ousted Mihailo in 1842 and replaced him as ruler by Karađorđe’s son, Alexander, thus furthering the rivalry between Serbia’s two royal dynasties.

UILDING ON THE

S

AVA

S

LOPE

During his rule from 1817 to 1839 Knez Miloš was wary of the pasha and his garrison of troops in Belgrade. The sultan’s promises did not fill him with confidence for his own safety since Ottoman actions in the past showed that local officials could easily take matters into their own hands. He preferred to put as great a distance between himself and Kalemegdan as he could afford and spent much of his time in the town of Kragujevac, the centre of the Serbian rebellions and loyal to him. Here he established his court and it remained the Serbian capital until 1842. He could not be entirely absent from Belgrade, however, and during his rule many changes were wrought on the face of the city.

After the Second Serbian Uprising, Belgrade was a settlement dominated by Kalemegdan as the residency of the pasha and the home of the Ottoman garrison. It had a mixed population of some 25,000, mostly Turks but with some Greeks, Vlachs, Jews, gypsies and Serbs. The Turks dominated the population on the slope down to the Danube, while the small Serbian community was concentrated on the Sava slope. The Muslim population, nervous at the extent of the Serbian rebellions and the new status of the province, went into a period of gradual decline. The number of Serbs grew, especially after the increased home rule granted by the decree of 1830.

At the same time, Ottoman styles of dress and architecture continued to act as the dominant models of urban life and the knez himself ruled more in the style of a pasha than a European prince. Fred Singleton wrote of him:

Miloš was a man nurtured in the old society, and his regime and life style still bore the marks of his origins. In 1830 in his house—or

konak

—there were no tables, chairs or beds. Visitors squatted on the floor or sat on low, Turkish-style divans. Miloš dressed in Turkish clothing. He was unable to read or write and books in Serbian were almost unknown. The main streets of the towns were rough mud tracks. Window glass was not used even in the ruler’s

konak

. There were no street lights and at night the streets were deserted.

Singleton calls the knez’s main residence a

konak

, a palace. The word can also refer to a place for an overnight stay whether an inn or quarters for guests as part of a monastery complex. Miloš’s Belgrade residence was over the hill at Topčider and out of sight of Kalemegdan, and more importantly beyond the range of the pasha’s guns. The main site of Serbian development, however, was in the area where they were already a majority around the Town Gate. The Serbian quarter stretched roughly from the brow of the hill and Knez Mihailo Street, down past the corner where the Cathedral, or Saborna crkva, stands to the River Sava, and over to the market now called Zeleni venac, the Green Wreath. A number of buildings from this early period survive, helping to give a picture of the style and taste of the time.

The road by the Sava now called Karađorđe Street runs from a point just below Kalemegdan as far as the main railway and bus stations. It formed a district called Savamala, inhabited by impoverished gypsies whom Miloš, in a typical display of ruthlessness, moved to the other side of town to a district called Palilula, on the Danube slope, just outside the trench marking the town limits. The area was open to river traffic and as such was developed for its trading potential. At the end of the street, where the Hotel Bristol stands today, there used to be the Little Market (Mala pijaca) to which traders from Bosnia would traditionally come arriving by boat at the wharf on the Sava.

Merchants from Belgrade’s Serbian community were among the first to build homes for themselves here. Their houses typically contained commercial premises on the ground floor with the upper storey used as living accommodation. No. 29 Karađorđe Street was built in 1828 by the Žujović family, and close by no. 37 was built in 1832 by Jakov Jakšić who served in Miloš Obrenović’s Ministry of Finance. Along the same street other houses were constructed, often with commercial intentions in mind, and also kafanas with rooms for visitors bringing their goods to sell or coming to buy in Belgrade (a

kafana

is a typical café serving food and drink). A new customs house was erected in 1835 by the Sava called the Đumrukana, of which there is no trace remaining but it had the distinctive honour of hosting Belgrade’s first theatre performance in 1841.

The street now looks rundown but it was the financial centre of nineteenth-century Belgrade. Situated by the river and prone to flooding, the land was marshy, but after the draining programme of 1867 it became more suitable for large construction projects, allowing proper hotels, the first stock exchange and apartment buildings to make their appearance. The opening of the main railway station in 1884 linked Belgrade with Vienna to the west and Istanbul to the east, establishing the city once again as an important point in the arteries of modern communication crossing the region.

Kosančić Crescent is a street further up the hill from Karađorđe Street. It contains hardly any traces from the time of Miloš Obrenović, but its development was of great symbolic significance. The trench, which was the city’s first line of defence, used to follow its course as it wound down to the Sava. The oldest building on the street is at no. 18, the house of Vitomir Marković erected in the middle of the nineteenth century, although there are some older dwellings on adjoining streets.

Some of these older houses are easily identifiable by their distinctive Balkan style of architecture. The Balkan style was common in nineteenthcentury Belgrade and exhibits many influences from Ottoman architecture, although it later adapted to include more European influences. Slobodan Bogunović in his encyclopaedia of Belgrade architecture describes some of its typical attributes: “The outer appearance of a house in the architecture of the Balkan style gives a picturesque impression with its overhanging, deep and shady eaves, jutting bay-windows, white-washed walls, garden verandas, tiled and gently sloping roofs, windows level with the façade and opening outward, and tall chimneys imaginatively decorated at the top.” The bay-windows are on the first floor and in some cases run the entire length of the façade. Otherwise, they may be oval or rectangular in shape, facing the street, with windows at the front and often at the sides to let in maximum light. Rooms in such a house were usually organized in a symmetrical pattern around a central hall that served to emphasize their externally balanced proportions. In poorer examples, the shape of the roof combined with low ceilings can give a somewhat squat appearance. There are a few examples of this Balkan style around Zadar Street, off Kosančić Crescent, as well as others of a later date with more classical or Baroque European features.

An architecturally interesting example is to be found at 6 Zadar Street, designed in 1928 by the architect Branislav Kojić, who was also responsible for the “Cvijeta Zuzorić” pavilion in Kalemegdan. Intending the house to be his family home, he fused traditional Balkan style with Modernist trends to produce a façade that combines both national and international elements.

Kosančić Crescent was known as the district of choice for Belgrade’s wealthier families in the nineteenth century. The view of it today is spoiled by the large empty plot between nos. 12 and 16, a result of the German air-raid on 6 April 1941 that brought Yugoslavia into the Second World War. The National Library of Serbia moved into a very elegant building here in 1925, only to be bombed and gutted by fire sixteen years later, an event which destroyed hundreds of thousands of volumes, rare books, maps, medieval manuscripts and donations left by private collectors. Almost the entire national cultural heritage existing in print form disappeared overnight. Great efforts have been made to repair the loss, but it is not unknown even now for a request for some item in the new building of the National Library to meet with the reply that it has not been in the collection since 1941.

Some other notable architectural landmarks can be found close by. No. 10 Gračanica Street is one of the oldest houses in the city, even predating the time of Miloš Obrenović, while 5 Gavrilo Princip Street, called Manak’s House (Manakova kuća), on the corner with Prince Marko Street, is constructed in typical Balkan style. The original building on this site contained the harem of a Turkish

aga

who found himself dispossessed of his property when the Serbs won greater independence. It was bought in 1830 by a Greek called Manojlo Manak who built the present house with a bakery and kafana. It was renovated in the 1960s and is now part of Belgrade’s museum complex.

The Green Wreath Market is at the top of Prince Marko Street, an area once covered by a large pond where people would come for a day out and boating. In 1840 a German lady opened a kafana here, but instead of putting a name over the door she displayed a piece of green tin representing a wreath—from which the modern name for the area is derived.

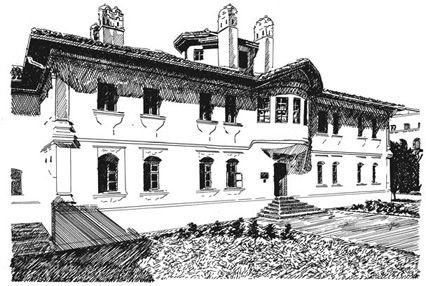

The Konak kneginje Ljubice, Kneginja Ljubica’s Palace, stands opposite the Cathedral on the corner of Knez Sima Marković and King Peter I Streets. Miloš, the kneginja’s (princess’s) husband, originally intended the house for himself as a symbol of his wealth, but it was too close to Kalemegdan for him to make much use of it. His wife then moved in with their two sons, Milan and Mihailo. The exterior expresses strong echoes of the traditional Balkan style, simply designed but larger than usual. The interior is of quite a different character, with a pattern of rooms and furnishings showing a distinctly European taste, probably due to the influence of the kneginja.

Over the years the building has fulfilled many different functions, reflecting Belgrade’s turbulent history. Ljubica was forced to leave in 1842 after the coup which brought the Karađorđević family back into power. It then housed the Belgrade Lycée, a school founded at Kragujevac but which was moved to the new capital. It was then given to the Ministry of Justice in 1863 and became a school for deaf and dumb children in 1918. When the communists took power in 1945 it became the Republic Bureau for the Protection of Monuments of Culture. During the 1970s it was completely renovated to house a museum collection displaying interiors of Belgrade homes from the nineteenth century.

Across the road at 5–9 Knez Sima Marković Street is another large and architecturally impressive apartment building, but constructed in a completely different style at the turn of the twentieth century. Building work began in 1880, but was only completed following a second phase of activity in 1910. It has a richly decorated façade sporting small balconies with wrought-iron fencing. Its long frontage has a distinctive Central European feel in complete contrast to Kneginja Ljubica’s Palace across the road. The differences between the two buildings are a visible record of how far the city shifted in its cultural orbit in a period of eighty years.

AFANA

AND

C

ATHEDRAL

Around the corner from here and across the road from the Cathedral is the well-known Belgrade kafana The Question Mark (Znak pitanja), represented outside by the simple sign “?” The story goes that when the first kafana opened here, the priests from the Cathedral, aghast that a drinking establishment could stand opposite a house of prayer, stole out one night and painted out the name. No-one could remember what it was actually called, so it became “?” The truth is not quite so fanciful. The building dates from the early 1820s, when it was built by one of Miloš’s functionaries, Naum Ičko, from whom the knez bought it in 1824. He gave the property to Ećim-Toma Kostić, the doctor who cured him when he was wounded in 1807 at the attack on the town of Užice during the First Serbian Uprising. The new owner opened a kafana under his own name Ećim-Tomina. Records show that he introduced a billiard table in 1834, one of the few available in the Balkans and a very popular attraction. In 1878 the kafana was renamed At the Shepherd’s (Kod pastira), and later At the Cathedral (Kod Saborne crkve). It was bought in 1884 by Ivan Pavlović, an enterprising businessman who added an extra dimension to the kafana by selling priests’ robes and other church paraphernalia. Much of what he sold was cheap trinkets, but it is not entirely clear which aspect of his trade offended the church authorities more—the sale of inferior icons or the name of his establishment, At the Cathedral. Eventually they decided that things had gone too far and threatened legal action unless Pavlović changed the name of his kafana. Not knowing what to do, he decided to put a “?” over the door and wait for the affair to quieten down. His temporary solution became the name that stuck.