Belisarius: The Last Roman General (17 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Belisarius appointed commander

With everything ready for the invasion, all that was needed was a commander for the operation. Mundus, the

magister militum per Orientem

was reappointed

magister militum per Illyricum

in January 532. It is possible that at this time Belisarius was once again made

magister militum per Orientem,

although the actual dating of his appointment is obscure; he was definitely filling the post by February 533.

The choice of Belisarius has always been seen as obvious: he had proven himself in the Persian Wars by his superb generalship, he was a personal friend of the emperor, and he had recently proven his loyalty in the Nika Riots. Assured of victory due to his military gifts, he would not then rebel and set himself up as a rival to Justinian in Africa.

None of this makes sense. In Chapter 4 it was shown that Belisarius had lost the early, unnamed battle in Armenia, had been present for the defeat at the Battle of Tanurin, and had commanded at the battles of Mindouos and Callinicum, two further defeats. The only battle he had won was at Dara. Although this had been a superb victory won by outstanding generalship, the winning of one battle and the loss of four – although admittedly he may not have been in charge at two of them – does not indicate superior military ability.

Yet despite his defeats at the hands of the Persians, Belisarius had recently been cleared of incompetence by the inquiry led by Constantiolus. His conduct at Dara had shown that he did have considerable talent, although this was not always in evidence, so the potential for victory was there.

His friendship and loyalty to Justinian are beyond question, but again on their own they do not justify Justinian’s decision to send Belisarius to the west. There must have been more to Justinian’s choice of commander.

The reasons can be found in evidence regarding Belisarius that has already been seen. One of the major reasons for the choice of Belisarius was linguistic. Most of the generals of the eastern empire now spoke Greek rather than Latin: the population of Africa spoke Latin. Although it would be possible to provide a translator for a Greek-speaking general, and although it is probable that most senior generals had been taught Latin, a ‘native’ speaker such as Belisarius would have been the preferred choice, since he was less likely to antagonise the native Africans either by his attitude or by misinterpreting their language. Furthermore, Justinian was aware that western Latin speakers believed that Greek-speaking easterners were effete, untrustworthy Greeks. This made the Latin-speaking ‘westerner’ Belisarius – born in Germana , in or near Illyricum, a ‘western’ province – an obvious choice.

As a final confirmation of his suitability, there is the passage from Zacharias previously quoted, showing that Belisarius ‘was not greedy after bribes, and was kind to the peasants, and did not allow the army to injure them.’ The last thing Justinian would want would be to conquer the Vandals only to have the native Africans rise in revolt due to the troops being arrogant and treating them poorly; the idea was to conquer, not to have to repeatedly send troops to crush unrest.

Taking everything into account, there is unlikely to have been any other general in the service of Justinian who was as suitable as Belisarius to wage war in the west: the reinstated

magister militum per Orientem

would lead the expedition to Africa.

Preparation and Departure

In 533 Belisarius was officially given supreme command of the expedition. There was to be no dual command, as had been used in the east; Belisarius was in sole control, with the emperor confirming his position in writing. In order to reduce the burden of command, Justinian appointed Archelaus, a man with great experience who had previously been praetorian prefect of Byzantium and Illyricum, as prefect of the army and so in charge of the logistics

Justinian placed at Belisarius’ disposal a mixed force of infantry and cavalry. According to Procopius (Proc,

Wars,

III.xi.1–21), the main force was composed of 5,000 Byzantine cavalry under the command of Rufinus, Aigan, Barbatus and Pappus, and 10,000 infantry, under the overall command of John, a native

of Epidamnus/Dyrrachium, supported by Theodorus Cteanus, Terentius Zaidus, Marcian and Sarapis. A further element was a contingent

oi foederati

led by Dorotheus

(magister militum per Armemam)

and Solomon, Belisarius’

domestic™.

Included amongst the generals were Cyprian, Valerian, Martinus, Althias, John and Marcellus. At about this time Justinian received a reply from the Vandal rebel, Godas, in Sardinia, stating that the troops would be welcome but that there was no need to send a commander. As a consequence, Cyril, one of the leaders of

the foederati,

was appointed to lead the expedition to Sardinia along with 400 men and was ordered to sail with Belisarius. Unfortunately, we are given no clear indication by Procopius as to whether the 400 men sent to aid Godas were included in Procopius’ overall total for Belisarius’ army or were an additional number of men.

Finally, there were two groups of mercenaries: 400 Heruls under Pharas and 600 Huns under Sinnion and Balas – the latter two being praised as men ‘endowed with bravery and endurance’ (Proc,

Wars,

III.xi.13.)

Serving alongside Belisarius were his personal

comitatus,

including spearmen, guardsmen and his

bucellarn.

Procopius does not appear to have included either the

comitatus

or the mercenaries as part of the total of 15,000 men, so it is possible that Belisarius’ force amounted to at least 17,000 troops.

To carry the expedition 500 ships were gathered, varying in size between approximately 30 and 500 tons, being crewed by an additional 30,000 sailors (averaging sixty men per ship), mainly natives of Egypt, Ionia and Cilicia, with Calonymus of Alexandria as commander. To defend the transports, ninety-two

dromones

(literally ‘runners’: single-banked warships with decks covering the rowers) were prepared, with 2,000 marines to man them alongside their normal crew.

When taken together, the traditional view that Belisarius set sail with only 15,000 troops to conquer Africa does not appear to be correct. Certainly, the main body was the 15,000 men detailed by Procopius as being allocated to Belisarius, but the expedition also included 400 Heruls, 600 Huns, Belisarius’ personal

comitatus,

and 2,000 sailors ‘from Constantinople’ manning the warships, who had been trained to fight as well as row (Proc,

Wars,

III.xi.16). There is also confusion over whether the

foederati

and Cyril’s force of 400 men were included in the original total. Finally, there were 30,000 sailors. Even if we accept that the sailors on the transport vessels would not be very good as warriors and therefore do not add them to the total, this still leaves a force probably in the region of twenty thousand men. The equivalent of two old Roman legions plus

auxilia,

even in the earlier empire this would have been a force to be reckoned with. In 9AD Varus had lost three legions in the Teutoburgerwald, rated as one of the worst disasters in Roman military history. The invasion was not undermanned, nor was it a scratch force scraped together for a desperate adventure. It was a large, well-balanced force capable of overcoming the Vandals and may have contained a higher proportion of high quality, reliable troops than the armies stationed in the east.

Whilst the force was equipped along the lines of Byzantine forces as outlined in Chapter 3, there was a major difference between this army and that used by Belisarius at Dara and Callinicum: there was no opportunity to train the troops before departure. As we shall see, Belisarius would be forced by the weather to stop en route to Africa and this would allow him to organise the command structure, but at no point was he able to give the troops practice of working together as a unit. This was to have repercussions later.

The Invasion of Africa

In June 533 Belisarius and the army embarked at Constantinople and set sail, Belisarius being accompanied by his wife Antonina and his

assessor

and secretary Procopius.

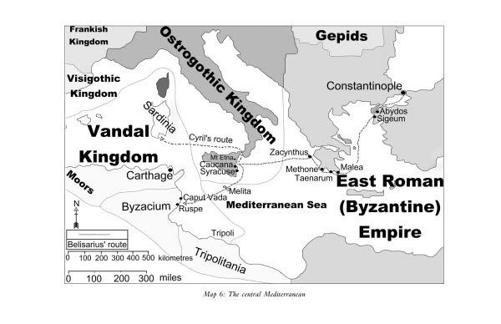

The fleet sailed from Constantinople to Heraclea Perinthus (Eregli, on the Sea of Marmara), where they waited five days for the arrival of a large number of horses from the Thracian herds. They then moved to Abydos, where they were becalmed for four days. During their enforced stay, Belisarius reinforced his authority when two drunken Huns killed a colleague. The two were executed and a message sent to the army that Belisarius was in charge and discipline would be enforced (Proc,

Wars,

III.xii.7-22).

Whilst in Abydos measures were taken to ensure that the fleet would not become dispersed in bad weather. The three ships in which Belisarius and his staff sailed were marked out so that they were easy to locate. They had a portion of their sails painted red and lanterns erected to make them visible both day and night (Proc,

Wars,

III.xiii.1–4).

Once the wind strengthened, the fleet proceeded to first Sigeum, then across the Aegean to Malea.

From there they went to Taenarum (Caenopolis: Cape Matapan) and finally to Methone. Here the army was joined by Valerian and Martinus along with a further contingent of troops – how many we are not told – and, due to the lack of wind, Belisarius decided to disembark the troops. This done, he formed up the army and organised his forces, detailing which troops were under the command of which officers. This would have been a very necessary requirement; with so many officers it would be easy for there to be confusion over command of the various troops and Belisarius averted the possible chaos that may have ensued upon landing in Africa.

It was at Methone that over 500 men died due to their eating infected bread, supplied, according to Procopius, by John the Cappadocian. Procopius alleges that instead of baking the bread properly, John had used the furnaces in the Baths of Achilles to save money, leaving the bread undercooked so that it

quickly turned mouldy in the summer heat. Belisarius immediately took steps, ordering that local bread be provided to the troops, and sending a report to Justinian. Apparently, John went unpunished for the deed (Proc,

Wars,

IILxiii. 12–20).

Once the troops who were able to had recovered, the fleet continued on to Zacynthus, where they took on fresh water to last them in crossing the Adriatic. Unfortunately, the winds were gentle and the water spoiled before the crossing was made. Only Belisarius and his table companions had fresh water; Antonina had had a small room constructed on board ship which she then part filled with sand. Pouring water into glass jars, she buried this in the sand and the water remained relatively pure (Proc,

Wars,

III.xiii.23–4). At last the ships arrived in Sicily, where they disembarked in a deserted area near Mount Etna.

We noted earlier that the movements of the general Cyril were unclear. Originally bound for Sardinia to help Godas, Procopius states that he joined Belisarius for the journey to Africa after Godas had declared that he did not need a Byzantine general, just some troops. It is clear that he sailed with Belisarius, but Procopius later has him rejoining Belisarius in Carthage following the Battle of Ad Decimum, after having discovered that Godas had been defeated and killed by Tzazon. The only logical place from which he could easily leave the expedition and travel to Sardinia was Sicily. As a consequence, it is likely that Cyril now set sail with his 400 men, planning to aid Godas in his rebellion.

Due to the length of the passage to Sicily, Belisarius had no up-to-date intelligence concerning the Vandals. According to Procopius,

[Belisarius] did not know what sort of men the Vandals were ... how strong they were in war ... in what manner the Romans would have to wage the war, or what place might be their base of operations ... [Furthermore], he was disturbed by ... [his own] soldiers, who were in mortal dread of sea-fighting. (Proc,

Wars,

III.xiv.1–2)

Accordingly, he sent Procopius to the city of Syracuse, ostensibly to purchase supplies. This had been provided for in the agreement reached between the emperor and Amalasuintha before the fleet set sail. In addition to buying goods, Procopius was given secret orders to reconnoitre and find recent information about the Vandals and their preparations for the upcoming war. They were to meet again at Caucana (Porto Lombardo), to where Belisarius was moving the fleet.