Belisarius: The Last Roman General (13 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Other close combat weapons

Maces, axes and whips could also be used by the cavalry, as well as the infantry, in a Sasanid army. Whilst the use of maces, axes and spears needs no explanation, it is likely that the whip was used in a similar manner to the Hunnic lasso. Whilst it could inflict wounds that were not lethal, its main function may have been to entangle the opponent and unbalance him, so enabling the warrior to dispatch him with relative ease.

Bows

Archery was returning to favour, as has been noted above, mainly due to the impact of groups such as the Huns and the Hepthalites. The Sasanid bow was of standard Central Asian composite design, and was employed by the majority of the cavalry as well as a proportion of the foot soldiers.

Sasanid archery relied on four factors for success: penetrative power, speed of delivery, volume of arrows and accuracy. The emphasis upon speed and concentrated volume in a small area is highlighted by a Persian device, the

panjagon

(‘five device’). This machine allowed five arrows to be fired with one draw, which, although not particularly accurate, did allow for a very large number of arrows to land simultaneously in a relatively small space. Unfortunately, none of these weapons has survived, so it has been impossible to replicate one and conduct experiments to establish how accurate the device was or measure the force and penetrating power of its arrows.

Siege Equipment:

Unlike the Parthians, the Sasanids learnt the art of siege warfare, probably from the Romans/Byzantines. To this end, they used the same type of siege equipment as the Byzantines. Although it is unlikely that they could greatly improve upon the Byzantine designs or methods, they soon came to match them in their skills in both the assault of fortifications and their defence.

Such, then, was the army with which Peroz now threatened Dara.

The Battle of Dara

The clash at Dara highlights one of Belisarius’ favourite tactics when fighting a battle. He was primarily a defensive commander, a theme that we will return to throughout the course of the book.

Roman/Byzantine battles against the Persians were historically fraught with danger. The high mobility of the Persian cavalry, and their resultant ability to control the battlefield, had only been partly offset by the previously-mentioned changes taking place within the Byzantine army – especially the greater reliance upon cavalry. The result of their tactical dominance had been their battlefield superiority in the preceding century. Belisarius was aware of this difficulty and he employed the time-honoured tactic of digging ditches to help compensate for his disadvantage, as shown in the diagram.

Yet the arrangement of the ditches suggests more; it is difficult to impose your will upon the enemy when they have the greater mobility, but Belisarius wanted to guide the battle towards a specific series of events. Therefore, the ditches were dug to a particular layout in the expectation of these events unfolding. In effect, the centre was advanced and the wings refused. Belisarius engineered events so that the main strike would occur on the flanks.

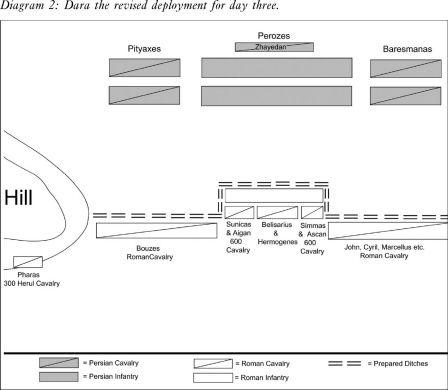

Stationed behind the front trench were the infantry, with a reserve of cavalry, under Belisarius and Hermogenes. Echeloned back and to the left of the infantry and positioned behind the ditches were Buzes with some Byzantine cavalry and Pharas the Herulian with 300 Herulian cavalry. To the right of these, stationed behind the infantry and so out of sight of the Persians, were Sunicas and Aigan with 600 cavalry. The right wing mirrored the left: a large force of Byzantine cavalry was stationed on the right behind the ditches, and behind the infantry to their left were Simmas and Ascan with 600 cavalry.

The plan appears to have been simple: the Persian wings would advance and slowly force back the relatively-weak Byzantine cavalry, with the ditches helping to keep the Persian advance at a slow pace. Once they had advanced past the reserve cavalry units stationed behind the infantry, these would be able to attack the Persian cavalry in the flank and rear, hopefully causing them to panic and rout. The task of the infantry was to maintain their position and pin the enemy centre.

As the Persians approached, their leader, Perozes (described by Procopius as

mirranes,

possibly equating to the

marzban

of the Persian army) sent a message to Belisarius to prepare a bath for his arrival. Belisarius ignored the message, but ensured that all was prepared for battle the following day.

On the morning of the next day, both sides drew up in their battle formations, the Byzantines as described above and the Persians in deep formations, then stopped. Both armies waited. The Persians believed that if they waited until after noon, the Byzantine troops, who usually ate before noon, would be hungry and weaker, so would in all likelihood give way. The Persians, who traditionally ate later in the day, would then prove to be the stronger. Therefore it was not until the afternoon that a force of Persian cavalry on their right wing attacked the troops with Buzes and Pharas. The Byzantines retired a short distance to their rear, but the Persians – possibly sensing a trap – refused to pursue. Consequently the Byzantines advanced again and forced the Persians to retire in their turn.

Shortly after, there was a challenge to single combat by a Persian youth, who was killed by Andreas, a trainer in a wrestling school. A further challenger was also killed by Andreas, before the armies retired to camp for the night.

On the second day, the respective generals realised that any attempt at battle was hazardous given the equality of forces and so they exchanged letters in an attempt to entice either the enemy to withdraw or to accept battle at a disadvantage. The attempt failed.

By the third day Perozes had been reinforced by 10,000 men and, with his numerical superiority assured, the Persian army prepared for battle. Perozes divided his army in two, forming two parallel lines, each formed of an infantry centre flanked by cavalry. The 10,000 men of the Zhayedan (Immortals), he stationed in reserve behind both lines. The idea was to rotate the front and back lines, enabling tired troops to have a rest whilst still keeping the Byzantines under intense pressure. Perozes himself controlled the centre, with Pity axes on the right with the Cadiseni, and Baresmanas on the left.

However it was also on the third day that Pharas, the leader of the Heruls, suggested a small alteration in the Byzantine plan. He proposed that he lead his Heruls behind the hill on the left flank, then, when the enemy were fully engaged, he would lead them over the hill and strike the Persians in the rear. Belisarius and Hermogenes approved the plan, and the cavalry under Buzes expanded their frontage to cover the gap this created, thus ensuring the Persians did not detect that part of the cavalry force was now missing from its place in the line.

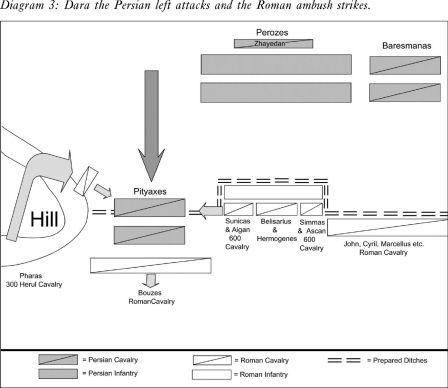

After again waiting until the afternoon, the Persians finally closed the distance between the armies and an exchange of missiles began. The advantage that the Persians had with more men and their rotation system – which went unnoticed by the Byzantines – was offset by them firing against the wind. Once the supply of missiles was exhausted, the cavalry of the Persian right wing advanced to contact.

After fierce fighting, the Byzantine left was driven back and was beginning to give way when the Heruls under Pharas appeared over the crest of the hill and charged into the flank and rear of the advancing Persians. As Pityaxes’ men wavered, Sunicas and Aigan with their 600 men attacked them in the other flank. The Persians broke and fled back to the shelter of their infantry, leaving 3,000 dead behind them.

Meanwhile, Perozes reinforced his left flank with some troops drawn from the second line and the Zhayedan in preparation for an assault on the Byzantine right wing. Fortunately, this was seen by Belisarius and Hermogenes and they accordingly ordered some of their own reserves, plus the troops under Sunicas and Aigan, to join Simmas and Ascan, sheltering behind the infantry on the right flank.