Belisarius: The Last Roman General (33 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

To the west of the river, the Moors and Byzantine cavalry led by Valentinus had again advanced to within missile range of the Goths before settling down to deliver a steady flowof missiles against the enemy. The Goths remained as they had deployed, slightly to the front of their camp, fearing that the Byzantines were trying to lure them into a trap. From a distance the volunteers looked like regular troops, and the Goths believed that the Byzantine cavalry was trying to force them to charge to allow the infantry to manoeuvre between themselves and their camp.

At about midday the Roman volunteers suddenly charged the Goths. Panicked by the unexpected attack, the Goths fled to the cover of the nearby hills, failing even to defend their camp. The attack was to be the undoing of the Byzantines.

The Goths had been frightened by the sheer numbers of the enemy. Yet the Byzantines failed to pursue the fleeing Goths or to destroy the Milvian Bridge, which would have isolated the Goths under Marcian and freed the entire west side of the city from attack. Nor did they cross the bridge themselves to attack the forces of Witigis from the rear. Any of these actions could have changed the outcome of the battle. Instead, the undisciplined forces that had scattered the Goths entered the camp and began to loot it of its valuables.

As the volunteers and the regular troops mingled, Valentinus tried in vain to restore order. Observing the chaos from their vantage point in the hills, Marcian and the Goths regained their courage and charged at the disordered troops on the plain. The Romans and Byzantines were destroyed, many being cut down as they sought the sanctuary of the city walls. The battle had been a disaster, and the Byzantines did not make any further attempt to engage the Goths in open battle.

Belisarius and Witigis as Commanders

Belisarius’ role in the defeat is minimised by Procopius. The statement by Procopius that the troops put pressure upon Belisarius to fight may be true, in which case he must still bear a portion of the blame. Yet it may also be false. It is possible that Belisarius himself wanted to fight and was willing to lead the troops into battle. The description of an unwilling Belisarius may simply be a traditional method of averting the blame and placing it firmly with the troops -compare this to Procopius’ description of the troops demanding action before their defeat at the Battle of Callinicum (as seen in Chapter 4). It is interesting to note that in both of these battles Belisarius was either ‘forced to fight by the troops’ and was defeated, or lost the battle and blamed the troops.

It is possible that the defeat was a major miscalculation by Belisarius. Still heavily outnumbered, he may have estimated that the large number of casualties caused by the regular small-scale sallies had reduced morale amongst the Goths, meaning that they would be liable to panic and flee when faced with a much larger force. If so, his guess was hugely mistaken. The troops withstood a barrage of enemy missile fire, for the most part without the ability to strike back. Discipline and morale in the Gothic army remained high. Belisarius’ strategy was a failure.

Witigis, on the other hand, gains a lot of credibility from the battle. Although his tactics were uninspired, they were the cause of the victory. Furthermore, his ability to restrain his troops and allow the Byzantines to tire themselves out before delivering a charge that quickly routed the enemy speaks of a Gothic confidence in their commander that in this case was justified. The only incident that stopped the victory from being devastating was the courage of the minority of the infantry under Principius and Tarmatus who fought and covered the retreat to the city. Without them, Byzantine casualties would have been far higher, with unknown consequences for the remainder of the campaign.

Aftermath of the Battle

Recognising the danger of open battle, Belisarius reverted to the earlier hit-and-run tactics that had proved so effective against the Goths. Procopius states that in these Belisarius was ‘generally victorious’ (

Wars,

VI.I.2). This suggests that on most days the tactics worked, but that occasionally the Byzantine cavalry was caught before they could reach the safety of the city, though possibly without losing too many casualties. This reinforces the idea mentioned earlier that Belisarius relied upon the superior quality of his bodyguards and

bucellarii

in these attacks: it is likely that the defeats occurred when a less experienced commander was given control of the sortie and had failed to react in time to the Gothic approach, in much the same way that the Goths had been defeated when they had tried to replicate the ruse and had been surrounded. In the same passage Procopius also indicates that sometimes infantry was sent out alongside the cavalry, possibly with a view to increasing their confidence and experience and so allowing them to become fully integrated with the cavalry as a fighting force.

Procopius gives several examples of such sallies. One of these involved the general Constantinus leading the Huns out onto the Plains of Nero. Late in the afternoon Constantinus realised that the Goths had advanced to close range and were now too close to allow the Huns to retire in safety. Therefore, he led them towards an area where there stood several ruined buildings and a stadium, ordering the Huns to dismount in the narrow lanes between them, where they were safe from mounted assault. His men now began a devastating fire upon the enemy. Finally, when it became evident that the Huns would not soon run out of arrows and their losses continued to mount, the Goths retired in disorder, pursued by the remounted Huns. The Huns then returned to the city.

All of these episodes display that Belisarius, while an an able commander himself, was also ably supported by subordinates who were capable of assessing situations on their own and reaching sound military conclusions.

As the spring equinox arrived, so did the pay for the troops. Euthalius landed at Tarracina with the money, and Belisarius arranged a diversionary attack to allow him access to the city in safety. In the course of these distractions three members of Belisarius’ guard were injured by the Goths and their medical attention detailed.

Cutilas, a Thracian, was struck in the head by a javelin, but continued to fight. After the battle, the javelin was removed, but since it was embedded in his skull, the force needed was excessive; he contracted phrenitis, an ‘inflammation of the brain’, and later died.

Bochas, a Hunnic officer of the guards, was attacked by twelve Goths. One assailant pierced the flesh under his arm and another cut him diagonally across the thigh, both areas which the armour did not cover, As a note to those who study the efficiency of ancient armour, the other ten blows struck his body armour and were turned aside. Unfortunately, the cut across his leg seems to have severed an artery and three days later he also died.

The last of the three, Arzes, was struck by an arrow between his nose and right eye. The physicians were worried about the amount of damage that would be caused by withdrawing the arrow, since the barbs were likely to cause severe injuries when they were pulled backwards. However, one named Theoctistus, feeling the back of Arzes’ head, realised that the head of the arrow had gone almost all of the way through. Therefore, he ordered that the shaft of the arrow protruding from Arzes’ face be cut off, and then proceeded to cut the back of Arzes’ head where the head of the arrow seemed to be resting. Uncovering the head of the arrow, Theoctistus pulled the rest of the arrow through the back of Arzes’ head, so removing it without doing any further unnecessary damage. Interestingly, Arzes survived the experience with hardly a scar.

Shortly after the spring equinox, famine and disease began to affect the citizens and troops in Rome. This result illustrates the wisdom and foresight of Witigis in capturing Portus; unable to use the river to transport supplies to the city, the need to transport food by road drastically reduced the daily amount reaching the city. Now, with the outbreak of disease, the Goths ceased to fight as they did not wish to contract the illness themselves.

Instead, Witigis decided to further reduce the level of supplies reaching the city. To the south of the city was a place where two of the great aqueducts approached each other before dividing again to make their separate entries to the city. At this junction the Goths built walls and so created a fortress which they manned with 7,000 warriors in an attempt to cut the supplies coming by road from Ostia, presumably via the Porta Ostiensis. The measure worked, as the situation in the city now became desperate and the citizens demanded that they be allowed to join Belisarius and fight a battle against the Goths. Belisarius refused, claiming that reinforcements were on the way and that shortly he would be able to take offensive action with regular troops.

Accordingly, sometime in September/October 537, Belisarius sent Procopius to Naples to muster all available troops, including any available reinforcements that had arrived, and supplies, ready for transport to Rome via Ostia. There was a rumour that reinforcements had landed and were currently scattered around Campania. Procopius left the city at night by the Porta Ostiensis (St Paul’s Gate) along with a small bodyguard led by Mundilas to escort him past the newly-created fort guarding the road. As Procopius travelled to Naples, Mundilas and his men returned to Belisarius and informed him that the Goths were not mounting patrols or even moving from their camps at night.

Sensing that Gothic morale was declining, Belisarius sent out cavalry detachments to local strongpoints with orders to restrict Gothic foraging parties. In effect, the Goths were now to be besieged within their own camps, leaving the Byzantines free to gather food and supplies from the neighbourhood without being attacked. Belisarius had previously attempted a similar enterprise earlier, sending Gontharis and a force of Heruls to Albanum. At that time, however, they had been forced to return when attacked by the Goths.

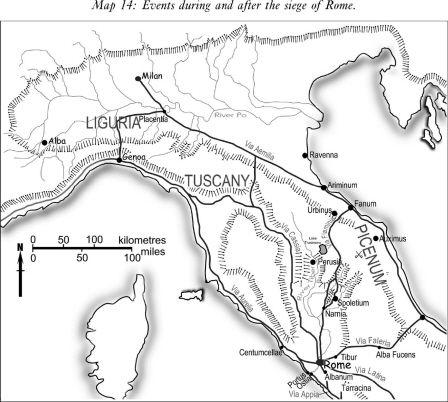

Now, he sent Martinus and Trajan to Tarracina along with 1,000 men. Part of the force was to garrison the city, Martinus and Trajan were to escort Antonina to the relative safety of Naples before setting up strongpoints in Campania to harass the Goths in that region. Similarly, Magnus and Sinthues with 500 men were sent to repair and man the fortress of Tibur, whilst Valerian and the Huns were sent to the Basilica of Saint Paul, which lay 14

stades

(around 1½ miles ) south of the city of Rome on the banks of the Tiber, to set up a camp and harass the Goths. Once the base was established, Valerian returned to the city.

The strategy worked; shortly afterwards the Goths began to suffer the effects of famine and disease broke out in their camps, especially that set up to the south between the aqueducts. Unfortunately, the Huns too began to suffer from famine and so left their camp and returned to Rome.

As these events unfolded, Procopius gathered supplies and placed them on board ships ready to sail to Ostia, He also managed to assemble a force of 500 men to reinforce Rome. When he was joined by Antonina, they waited for the orders to return to Rome.

Belisarius regains the initiative

At last, freed from other theatres of war, reinforcements now began to arrive in Italy. The first was a contingent of 300 cavalry led by Zeno, who arrived in Rome using the Via Latina from Samnium. Shortly afterwards, 3,000 Isaurians under Paulus and Conon arrived in Naples, and 800 Thracians under John, nephew of Vitalianus and

magister militum,

along with 1,000 regular cavalry under various commanders, landed at Dryus (see Map 11). These now gathered in Naples before moving to Tarracina, where they joined Martinus and Trajan. The ships with their supplies were ordered to proceed to Ostia, which was still in Byzantine hands.

Fearing the Goths would attack the newly-arrived troops as they moved towards Rome, Belisarius devised a new stratagem as a diversion. Realising that the Flaminian Gate had been blocked, the Goths had built one of their camps close by in order to threaten the walls. At night Belisarius had the wall blocking the gate removed so that he once again had free access to and from the gate. At daybreak, Trajan and Diogenes were sent out of the Pincian Gate with 1,000 cavalry and ordered to attract the full attention of the Goths, if possible forcing them to pursue the Byzantines as they retreated. Trajan and Diogenes were successful, and as the Goths set off in pursuit of the Byzantines, Belisarius led his men out of the Flaminian Gate. Although the new forces failed in their attempt to capture the camp, the majority bypassed the strongpoint and so fell upon the rear of the pursuing Goths. Trajan and Diogenes now rallied their men and charged the Goths from the front. Attacked from both sides, the Gothic forces disintegrated, most being killed and the survivors fleeing to the camps. The Goths were now in no condition to attack the reinforcements as they approached the city.