Belle (20 page)

Authors: Paula Byrne

Margaret Middleton’s impact was huge. In 1784 it was she who had persuaded James Ramsay to publish his account of the horrors of the slave trade,

An Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies

. This was the first time that the British public had read an anti-slavery work by a mainstream Anglican writer who had personally witnessed the suffering of the slaves on the West Indian plantations. Christian Ignatius Latrobe, a leading figure in the evangelical Moravian Church who spent many years at Barham Court, wrote to his daughter that the abolition of the slave trade was the work of one woman, Margaret Middleton.

11

But the presence in another grand but more peaceful house – Kenwood – of another woman – Dido Elizabeth Belle – was also a hidden element in the story of abolition.

Lord Mansfield would not live to see the end of the slave trade. By the time that the abolitionist forces were gathering at Barham, he was growing frail. In 1785 he wrote to the Duke of Rutland: ‘I go down hill with a gentle decay, and I thank God, without gout or stone.’

12

On 1 November that year, the

London Chronicle

reported that the Lord Chief Justice ‘has been obliged to give up the pleasure of riding on horseback owing to a weakness in his wrists’ – it was rather remarkable that he had stayed on a horse so long, given that he was eighty.

His popularity was waning. There were rumblings in the press that he was losing his judgement, and that retirement was overdue. Caricatures began to portray him as an old dodderer. One particular engraving even cast aspersions on his beloved dairy farm at Kenwood, which was presumably run by Dido alone now that Lady Mansfield had passed away. Entitled ‘The Noble Higglers’ and published in the

Rambler’s Magazine

on 1 February 1786, it shows four figures in a landscape, on a road leading from a country house. A judge, evidently Mansfield, carries a pair of milk pails on a yoke, while his companions bear pigs and poultry. It was published as an illustration to a letter about two peers, one of them Mansfield, who were in the habit of selling their dairy produce at Highgate. Surely, the letter suggests, they should be liable to the shop tax.

13

Finally, in 1788, Mansfield retired from his role as Lord Chief Justice. He remained at Kenwood, looked after by Dido and his other nieces, the Ladies Anne and Margery Murray, for the last few years of his life. When Fanny Burney visited Kenwood in June 1792 she was unable to see Lord Mansfield, as he was too infirm. She was told by the housekeeper that he had not been downstairs for four years, ‘yet she asserts he is by no means superannuated, and frequently sees his very intimate friends’. Burney says that the Miss Murrrays ‘were upstairs with Lord Mansfield, whom they never left’. Fanny Burney asked after the Miss Murrays and left her respects. They had often invited her to Kenwood, and she expressed her sorrow that she hadn’t taken up the offer before then. There is, however, no mention of Dido.

On Sunday, 10 March 1793, Mansfield did not feel like taking breakfast. He was heavy and sleepy, his pulse low. Vapours and cordials were given to him. He perked up a little on the Monday, but all he asked for was sleep. He survived for another week, lying serenely in bed, but his silver tongue was silenced. He never spoke again.

14

He was buried in Westminster Abbey with great dignity. The obituaries described him as the greatest judge of the age, if not any age.

The story of Dido Belle and Lord Mansfield is about individuals who changed history. There are many heroes and heroines in this story – both ordinary and extraordinary. There is Mrs Banks, who spent so much of her own fortune on securing the release of Thomas Lewis; Elizabeth Cade, who refused Lord Mansfield’s request to buy James Somerset and so avoid the issue of English slavery; Lady Margaret Middleton, who set up the abolitionists’ headquarters in her own home. The many thousands of women who stopped buying sugar. Mary Prince, who published her memoir. The men, too. The lawyers on the Somerset case who refused payment; Lord Mansfield, who made the ruling; and Granville Sharp, who was propelled into the cause of his life by seeing the bloodied face of Jonathan Strong.

The woman we know so little about, Dido Belle, played her own part. Would Mansfield have described chattel slavery as ‘odious’, and have made his significant ruling in the Somerset case, if he wasn’t so personally involved in the ‘Negro cause’ as a result of his adoption of Dido? His language in the case of the

Zong

massacre, his description of the comparison of slaves to horses as ‘shocking’, his constant concern for questions of ‘humanity’, are entirely consistent with his personal affection and respect for her. His pride in bringing the two Princes of Calabar to London and his determination in freeing them makes evident his abolitionist sympathies. His confirmation of Dido Belle’s freedom in his will reveals his absolute determination that there should be no possibility of the realisation of the awful possibility of her being somehow sold into slavery.

Mansfield’s insistence on the limitations of his famous ruling seems to point more to his fastidious nature than anything else. He was scrupulous about following the letter of the law, and utterly focused on clarity and certainty within the law. Nevertheless, he knew what was at stake in the Somerset case. He seems to have felt genuine concern that his ruling would be perceived as favourable to the black cause because of his relationship with Dido: in the words of Thomas Hutchinson, ‘He knows he has been reproached for showing his fondness for her.’ Yet he let Somerset go free, and in Thomas Lewis’s case threatened to bring into custody any man who ‘dared to touch the boy’.

For much of English polite society before the Somerset case, slavery was not to be spoken about. It was out there, far away in the plantation fields and on the slave ships. It didn’t have to be faced, especially if the consequence would mean the sacrifice of sugar. The Somerset case, and its widespread publicity and legal ramifications, brought slavery into the spotlight. Just as the planters feared, after Mansfield’s ruling there was no going back.

On 25 March 1807 the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade received the royal assent and entered the statute books. William Wilberforce’s face streamed with tears of joy. One month later, William Gregson’s son James hanged himself at home in the Liverpool mansion built on the proceeds of slave labour.

Granville Sharp continued his battle for black freedom. His fame had spread, as is indicated by a letter he received from an African in Philadelphia who wrote, ‘You were our Advocate when we had but few friends on the other side of the water.’

15

A committee for the Relief of the Black Poor was set up by Sharp in the years following the Somerset ruling, and he began work on his plan to return English slaves to Africa, dreaming of their resettlement in Sierra Leone. Granville Sharp died in 1813 and, like Mansfield, has a memorial in Westminster Abbey.

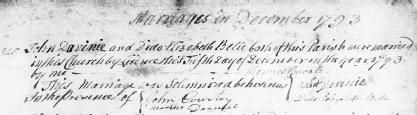

The marriage of ‘John Davinie’ and Dido Elizabeth Belle

What was to become of Dido now that Lord Mansfield was dead?

Overnight, she had become a woman of some means. Whether or not she was the ‘Elizabeth’ to whom her father John Lindsay had left a half share of £1,000, she now had the annuity of £100 a year for life in Lord Mansfield’s original will, the sum of £200 ‘to set out with’ in the first codicil, and the further £300 in the second. The consequence was clear: she had money of her own, so she could not expect to live at Kenwood with Lord Stormont and his family. Having been loved and cherished, living in splendour there all her life, she now had to face the harsh reality that she was to be turned out of her home. With Mansfield’s death she had lost her friend and protector.

Dido had turned thirty, and no doubt would have considered herself past marriageable age. Her cousin, now Lady Finch, had two children, and was happily settled in Kent. She apparently did not offer Dido a home. Dido would seem to have had little chance of meeting suitable men, yet within nine months of her uncle’s death she was married. Her husband was a servant of French extraction called John Davinie, Davinière or, most commonly in the surviving documentary records, Davinier.

1

How she met him remains a mystery. The likeliest possibility is that it was through Lord Stormont, the new Earl of Mansfield. As a result of his time as ambassador in Paris, and his close connection with the French court, Stormont had a number of French servants working for him in London and at Scone. Some of them may even have been well-born refugees from the French Revolution, to whom he gave shelter and employment. There is a surviving accounts book of Stormont’s which lists numerous French servants, though none with the name Davinier. It seems highly probable that upon moving into Kenwood, Stormont took it upon himself to solve the problem of Dido by setting her up with one of his own men, or a French servant otherwise known to him.

Dido could never have made a match as brilliant as that of her cousin Elizabeth. Her status was uncertain. She was certainly more than a servant, and had noble blood in her veins, but as a ‘natural’ daughter, she could not expect the same privileges and opportunities as a child born in wedlock. Nevertheless, her inheritance set her well apart from the servant ranks. Financially, she was better off than many genteel women of her era. Dido also had her beauty, her ‘amiability and accomplishments’. She was educated. It was a good match for John Davinier.

On the marriage licence, it states that John Davinier was resident in St Martin-in-the-Fields, the parish of Lord Stormont’s townhouse. The entry in the marriage register for St George’s, Hanover Square, dated 5 December 1793, says that both bride and groom were of that parish. Dido signed with her full name, ‘Dido Elizabeth Belle’. The witnesses were Martha Davinie, who was presumably John’s mother or sister, and a man called John Coventry. The latter could conceivably have been the Honourable John Coventry, younger son of the Earl of Coventry, or perhaps it was a certain John Coventry, ‘citizen and joiner’, who held the freedom of the City of London.

2

St George’s was one of the most fashionable churches in greater London. The couple were married there by licence. This was more expensive than being married by banns, and was sometimes perceived as a status symbol. Often the upper classes were married by licence, to avoid the banns being read out three successive times in church. This meant you could be married more quickly, and was also convenient if you were from a different parish.

The following year Dido changed her surname on her banking account from Belle to Davinier. A year later, she gave birth to twin boys, Charles and John, though it appears that John did not survive infancy. The name Charles was presumably chosen because of a Davinier family connection, while John would have been either for Dido’s husband or her father, Sir John Lindsay. Another son, William Thomas, was born in 1800.

3

His first name was clearly chosen in homage to the memory of Lord Mansfield.

Land tax payments – the equivalent of modern property tax – reveal that John and Dido Davinier lived in Pimlico. An 1804 map of the area shows that it was largely fields at that time, though it was rapidly being built up. The ground was swampy, with creeks running from the Thames. It was essentially a middle-class area, not a fashionable one. The Daviniers lived on Ranelagh Street. This had long been an open roadway, with just a few houses on one side, but the north end had undergone development. A typical property was described as ‘A neat leasehold house, very pleasantly situated … containing two rooms on each floor, with convenient offices and a large garden.’

4

One of Dido’s neighbours was the miniature painter and engraver Charles Wilkin. Others in the street were a mixture of trade and professional people. There was an architect called George Shakespeare, a dentist, a vicar’s daughter, a music seller (who went bankrupt), a herbalist called Mrs Ringenberig who, upon examination of morning urine, could provide surprising cures for female complaints (the offer of her services was a fixture in the classified ads of the London papers). Most were respectable types, but, as in any community, every now and then something untoward might lead to an unwelcome newspaper story. On one occasion a woman from Ranelagh Street was taken to court for having ‘put a live bastard child down the privy’.

Notable landmarks nearby were Locke’s Lunatic Asylum and two popular pleasure gardens. Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea was the more famous, boasting a superb rotunda, a Chinese pavilion and beautifully laid-out formal gardens. Dido’s home was closer to the rather less salubrious ‘Jenny’s Whim’, which was a popular tavern and tea garden in Pimlico.

5

The pleasure gardens were renowned as public spaces where different classes intermingled to walk, eat supper and attend musical concerts. They were also notorious as the haunts of prostitutes and the scenes of illicit assignations.