Bertie Ahern: The Man Who Blew the Boom: Power & Money (43 page)

Read Bertie Ahern: The Man Who Blew the Boom: Power & Money Online

Authors: Colm Keena

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Leaders & Notable People, #Political, #Presidents & Heads of State, #History, #Military, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Elections & Political Process, #Leadership, #Ireland, #-

Another invitee to the Ballyconnell get-together was Maureen Gaffney, who was asked to speak on the childcare issue, which continued to be a political challenge. She put her heart and soul into her address.

The entire issue during the Celtic Tiger years had been about labour supply and the need for more creches. I argued that this was a golden moment. I tried to re-orientate the debate towards the big issue: children and their future. I wanted money spent on early child care and education. There was absolutely no argument about the benefits. There is a boomerang effect, with a return for every euro invested.

It is particularly beneficial to the disadvantaged, but I argued that it should be universal. It can help support communities and [with a universal system] the most resourceful parents in the community become a resource to the service. I spoke with as much passion as I could muster.

The Government did take up some of the recommendations, but I was looking for a ‘big bang’ moment, something like the introduction of free secondary education. It could be a moment like that, a great legacy of the Celtic Tiger era.

I argued against giving money to everyone, which I suppose was a brave thing to do. I said there was no guarantee that it would be spent on children’s welfare. It might be spent on a foreign holiday, or to put in a deck.

Gaffney thought the politicians had a concern that giving money to early child care and education would be seen as discriminating against the stay-at-home mother, especially in the wake of the row over Charlie McCreevy’s introduction of individualisation for income tax assessments in his 2000 budget. She felt that the stay-at-home mother was something of a myth. Rich mothers didn’t work, but they put their children into creches so that they could pursue other activities. Extremely poor mothers didn’t work because they couldn’t afford child care.

Politics overshadowed the longer-term view. There was a very strong idea or ideology at the time that people should be given their money back. How receptive was Bertie? He invited me there. But I didn’t get the impression it was a eureka moment for him. I think he thought in a very political way.

Brian Cowen in his first budget speech in December 2004 announced another increase in child benefit rates and pointed out that they had increased by a whopping 270 per cent since 1997. But throwing vast amounts of money at the problem hadn’t made it go away. Indeed, it might even have fed into the issue. Just as there is a correlation between house prices and the amount of credit available, there is a correlation between the number of households where both parents are working and house prices. The greater the household income, the more a couple can afford to pay for a house, and the more house prices rise. The more expensive housing became, the greater became the pressure on young parents to both have jobs. Encouraging female participation in the work force created a positive-loop system, with one factor influencing the other in an upwards spiral.

In his budget speech of December 2005 Cowen announced the Government’s new childcare strategy. He said the Government wanted to help all parents by widening their options. ‘Having carefully considered all the complex issues involved, the Government has developed a five-year strategy to tackle the problem.’ The Government had decided to support the provision of more childcare places and to assist in the care in the home of children in their first year through extended maternity leave. It was going to address ‘cost pressures’ by providing an entirely new payment: an early childcare supplement for all children of less than six years of age. When announcing the measure, Cowen pointed out that child benefit that year would cost €2 billion. This compared with €500 million only five years earlier. He had decided that the most effective way of dealing with the continuing pressures being felt by the parents of young children was to introduce another payment. Everyone, regardless of whether the parents were both working or not, would receive €1,000 per annum per child until the child reached six years of age. The new scheme would cost €353 million a year. The Government was going to spend more on giving out money than it would have cost to establish a system of pre-school education, even though the world by then knew of its benefits.

In March 2009 the Competitiveness Council published a statement on competitiveness and training, which spoke about the need for a state-run system of pre-primary schooling for children of three years of age and more. Despite the recession that was by then well entrenched, the development of a universal pre-primary system was seen as a ‘key long-term priority’ mirroring the steps taken over past decades in primary, secondary, tertiary and ‘fourth-level’ education, it said.

Pre-primary education is considered the most important level of education in an individual’s cognitive development, as educational progress is cumulative for most individuals. Participation rates in state-funded pre-primary are extremely low in Ireland by international standards. The percentage of Irish three-year-olds in state-funded education in 2005 was 1.7 per cent compared to an

EU

average of 82.2 per cent.

A month later, when introducing an emergency supplementary budget, the Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan, announced the decision to scrap the early childcare payment introduced by Cowen in 2006.

It is of course true that what experts suggest should be done and what politicians believe to be politically achievable are two different matters. Nevertheless, the gulf between what many believed to be important requirements for the future development of Irish society and what the Ahern Governments chose to do was noticeably wide. This in turn, it should be noted, set an unfortunate example for people in all walks of life.

Chapter

16

BOIL AND BUBBLE

T

he short version of Irish economic history during the Ahern years breaks into halves to such an extent that it bolsters the case that it was the circumstances and management of the first half that led to the catastrophic events of the second. Indeed, in a speech to the Institute of International Finance in Washington in October 2010 the Governor of the Central Bank, Prof. Patrick Honohan, described what had happened to Ireland in exactly such terms. He referred to the American economist Robert Schiller, whose book

Irrational Exuberance

(2000) predicted the collapse of the dot-com bubble, which ended in March 2002. (The second edition, published in 2005, waved a warning flag about real-estate prices in the United States, which peaked in October 2007.) Schiller examined why markets can run wild and why bubbles occur. Included in his analysis were such non-economic issues as hype in the media, herd behaviour, the nature of optimism, and how people listen to others’ messages despite their better judgement.

Honohan told his audience that it was the half-truths of the late 1990s that had led to the myths of the 2000s. In a speech concerned with how Ireland’s banks could have lost so much money, he linked Schiller’s views and the Irish experience.

A pulse of optimism, built on a faulty analysis of the potential from some new technological or institutional development, starts a wave of optimism, reinforced by processes of collective psychology that build a myth on this half-truth. For Ireland, the combination of rapid but solid and sustainable convergence to full employment and high income in the 1990s—the period known as the Celtic Tiger—with the low interest rates promised by euro membership formed the basis of the myth or half-truth which triggered the bubble.

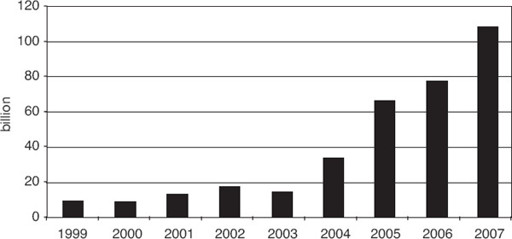

Fig. 2: Foreign borrowing by Irish banks, 1999–2007 (€ billion)

Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

The first-half, second-half analysis of the Ahern era can be divided in a number of ways. There is the first and the second Governments. There is the treatment of income tax: rates were reduced significantly during the period to 2001, while credits and bands were extended significantly in the period thereafter. McCreevy was Minister for Finance for the first half, Cowen for the second. The banks’ reliance on funds from abroad was modest during the first half but grew rapidly during the second. The wealth of the country was earned during the first half but borrowed during the second. Ireland had its own currency in the first half but was part of the euro for the second.

Half time does not fall at exactly the same moment for all these factors, but the structure of the narrative is fairly clear. It is not the intention here to go through all the factors in any detail, though one point deserves to be made: despite what Ahern would say later, he and his Government colleagues were warned about the dangers of the pro-cyclical budgetary stance they adopted for almost the entire Ahern period. Ahern did not respond to those warnings by having second thoughts about strategy or even by taking a breather and worrying for a bit before deciding to press on. Rather, he ignored what was being said and, if that didn’t work, reacted as if the warnings were threats to his political position, sometimes verbally assaulting those who had dared to speak. There is little evidence that any of his Government colleagues were opponents of what was going on.

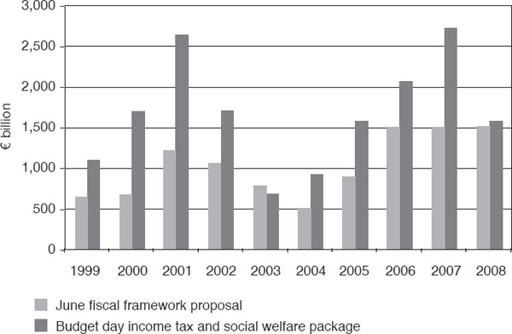

Fig. 3: Budget packages, 1999–2008

Annual budgets exceeded the advice of the Department of Finance. Note the spikes just before the two general elections.

Source: Rob Wright, report on performance of Department of Finance. Reproduced with permission.

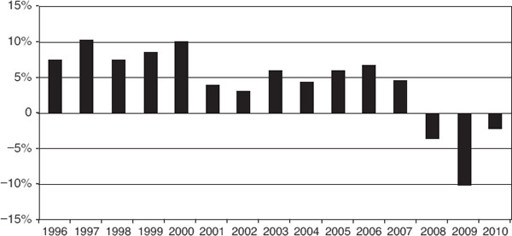

Growth rates such as 10.1 per cent and 8.7 per cent are phenomenal for a developed Western economy and are well above what economists would describe as sustainable. The collapse of the Irish economy at the end of the Ahern era was the largest for a Western economy in the period after the Second World War.

In money terms, the growth equated to a gross national product of €83 billion in 1996, €161½ billion in 2007 and €139½ billion by 2010.

GNP

is a measure that tends to exclude the activities of multinationals, which export their profits.

Fig. 4:

GNP

, annual change, 1996–2010