Between Giants (18 page)

Authors: Prit Buttar

Tags: #Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II

Elsewhere, Estonian guerrillas were operating against the Red Army. The Estonian

Omakaitse

(‘Home Guard’) was first created during the turbulent period between the departure of the Czar’s armies and the arrival of the Germans in 1917. The following year, it was renamed the

Kaitseliit

(‘Defence League’) and remained in existence until 1940. Although it was suppressed during the Soviet occupation, many members started up a new underground

Omakaitse

, and this provided the nucleus for the creation of several large groups of anti-Soviet guerrillas after the onset of

Barbarossa

. One large group of guerrillas, led by Major Friedrich Kurg, moved to seize the city of Tartu, midway between Lakes Võrtsjärv and Peipus. The group had been planning such an operation for weeks, even before the German invasion began; there had been informal talks with Tartu University Hospital about treating casualties as early as June.

There were three crossings over the River Emajõgi in the town, the ‘liberty bridge’ in the western part of the city, an old stone bridge, and a pontoon bridge. The pontoon bridge was dismantled on 6 July, and two days later, Red Army engineers began preparations to blow up the stone bridge. On 9 July, a demolition charge destroyed the northern end of the bridge. Later the same day, a German reconnaissance patrol attempted to enter the town from the north-west, but was beaten off. The guerrillas decided to attack the small remaining Soviet garrison the following day.

On 10 July, fighting broke out around the town as the Estonian guerrillas moved to secure key buildings. Another German reconnaissance patrol, led by Hauptmann Kurt von Glasenepp, entered the town, and the German armoured cars provided welcome fire support for the guerrillas. By the end of the day, the western half of the town was under the control of the Estonians, but the German armoured cars now withdrew to refuel and rearm. Aware that they lacked the strength to prevent the Red Army from moving back across the ‘liberty bridge’ into the western parts of the city, the Estonians sent an urgent message to the Germans outside the city asking for help.

Later that night, the Soviet engineers destroyed the ‘liberty bridge’, but fighting flared up again as the Soviet 16th Rifle Division moved towards the city. At the same time, a German task force, consisting of two reconnaissance battalions and an infantry battalion, commanded by Generalmajor Karl Burdach, was ordered to secure the city, and more guerrillas, including Friedrich Kurg and other former Estonian army officers, also entered Tartu. Fighting continued for several days, with much of the southern part of the city reduced to rubble. Further German reinforcements were fed into the battle, which continued until the end of the month.

33

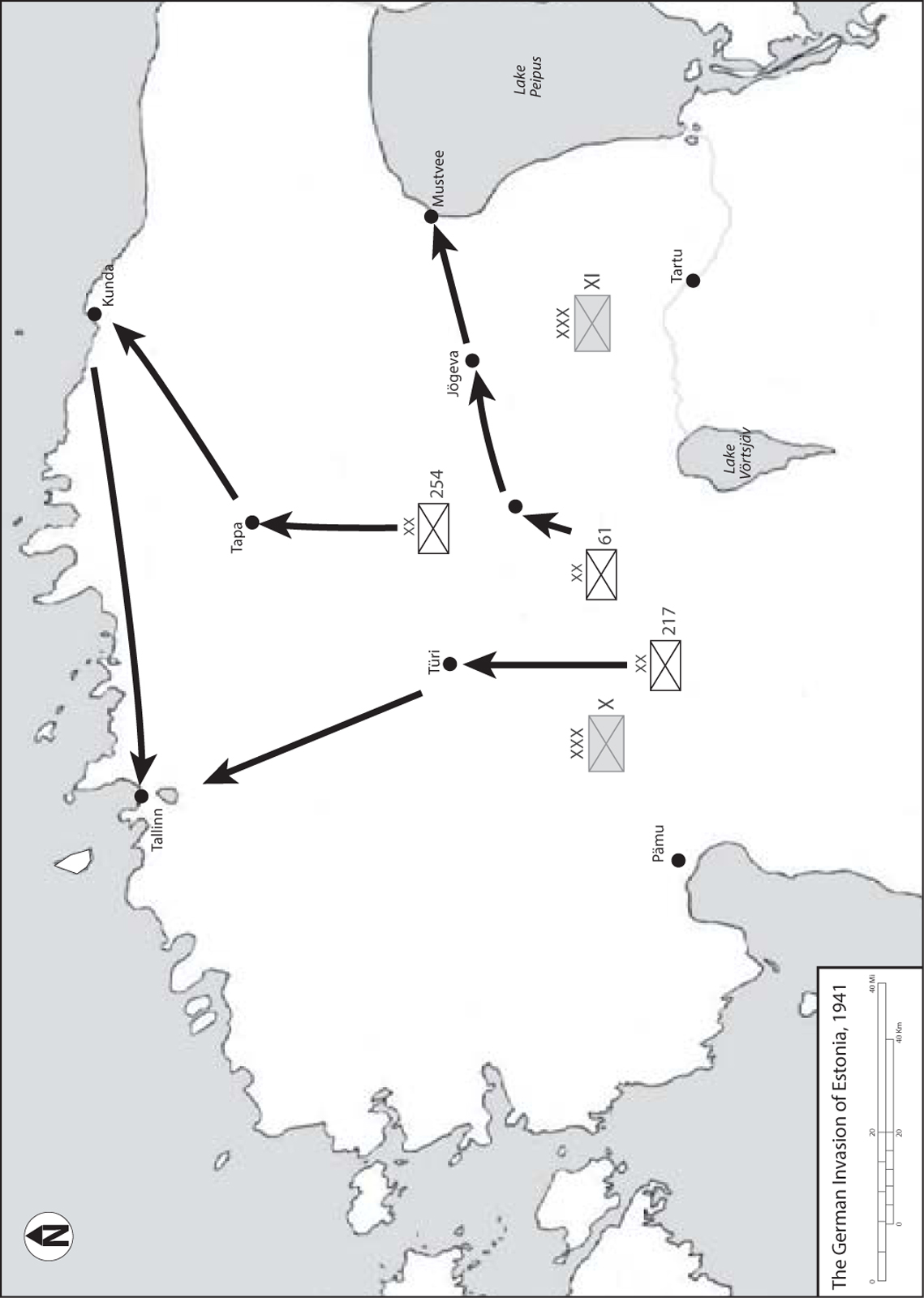

After pausing to regroup, 18th Army resumed its drive into Estonia on 22 July. The reinforced 61st Infantry Division attacked and seized Põltsamaa, north of Lake Võrtsjärv. The following day, as 217th Infantry Division joined the attack at Türi, 61st Infantry Division moved against Jõgeva, in an attempt to isolate the Red Army forces near Tartu. To avoid this, the Soviet 48th and 125th Rifle Divisions, together with the remnants of 16th Rifle Division from Tartu, withdrew a little to the north, but they were too late; on 25 June, 61st Infantry Division reached Lake Peipus near Mustvee, cutting off the Soviet forces. Fighting continued until late July, but repeated Soviet attempts to break out were blocked. Finally, on 27 July, the remaining men – nearly 8,800 – were forced to surrender.

With the newly arrived XLII Corps on the left and XXVI Corps on the right, 18th Army pushed north again on 29 July. XXVI Corps made good progress, striking at the seam between the Soviet 10th and 11th Rifle Corps; 254th Infantry Division reached Tapa on 4 August, and arrived at the Baltic coast at Kunda three days later. The two Soviet rifle corps were separated, with 11th Rifle Corps forced to withdraw towards Narva while 10th Corps fell back on Tallinn. German forces followed swiftly towards Narva, but were held up by gunfire from Soviet destroyers near the coast. It was only with the deployment of a heavy coastal artillery battery on 13 August that the destroyers were driven off. The three divisions of XXVI Corps slowly closed in on Narva, and finally took the city on 16 August. Pursuing the retreating Soviet troops, elements of the German 291st Infantry Division seized bridgeheads across the River Narva:

The old borderlands were reached. From the top of Hermann Castle [a fortress held for many years by the Livonian Knights] the terrain to the east was flat and forested, it was like the beginning of another world. Estonia, with its blue-black-white banners and its friendly people, was behind us; Russia proper, exotic and unknown, lay before the soldiers.

34

There remained the Soviet forces in and around Tallinn, and on the large islands off the western coast of Estonia. Outside Tallinn, General Walter Kuntze, the commander of XLII Corps, had three infantry divisions at his disposal. 254th Infantry Division was on the Baltic coast to the east of the Estonian capital, with 61st Infantry Division, freshly arrived from the destruction of Soviet forces south of Mustvee, to the southeast and 217th Infantry Division to the south. The western part of the German encirclement was made up of

Kampfgruppe Friedrich

, with a single regiment of infantry, and artillery and engineer elements of several formations. The defenders, the Soviet 10th Corps, had what remained of three rifle divisions, together with several battalions of naval infantry – a mixture of marines and sailors.

The battle for Tallinn began on 19 August. The approaches to Tallinn were protected by fortifications built by the Estonians during their war of independence, and subsequently strengthened, and the Germans made slow progress past the seven main strongpoints. Soviet warships operating close to the coast and from within the harbour added their firepower to the defence, but inexorably, the Germans advanced.

Reval [Tallinn] was burning. Tracers flew back and forth at the edge of the city. The towers of the old Hanseatic town were black against the bright night sky. As the morning fog cleared on 27 August, the heavy air and artillery activity resumed. Russian cruisers and destroyers joined in the land battle from the harbour, and the earth trembled under the impact of 180mm shells.

35

By the fifth day of the attack, the assault spearheads were within six miles of the city centre, and a day later, the fighting reached the main urban area. With no possible option of a breakout over land along the coast to the east, the Soviet forces began to make arrangements for a seaborne evacuation. The Germans were aware of these preparations, and in combination with Finnish forces, laid extensive minefields on the approaches to Tallinn; despite having considerable naval assets in the area, the Soviet Navy was unable to intervene, partly due to the weather. Luftwaffe air operations against the port area of Tallinn were increased, within the limits of availability of air support.

On 28 August, as the battle for Tallinn reached its peak and German troops pressed into the heart of the city, the Soviet naval evacuation began. Smokescreens were created in an attempt to hide the activity from the Germans, but heavy artillery fire killed perhaps 1,000 people waiting to embark on the ships. The first convoy, led by Captain Bogdanov, consisted of two destroyers, ten minesweepers and minelayers, five transports, and a number of smaller vessels. It left the port just before midday. Two hours later, two smaller convoys followed, with the main Soviet naval force, consisting of the cruiser

Kirov

, three destroyers, four submarines and an icebreaker, departing in mid-afternoon. German forces were waiting, and a torpedo boat flotilla of five vessels attempted to intercept the convoys. The German boats were driven off by the guns of the Soviet warships, but the minefields and repeated Luftwaffe attacks inflicted heavy losses. The first ship to strike a mine was the steamer

Ella

. Six destroyers, two submarines, four minelayers, and several transports were sunk, with a total loss of over 12,000 lives, during the two days it took for the Soviet vessels to reach Kronstadt. Nevertheless, some 28,000 people escaped to safety. In Tallinn, nearly 12,000 men had been left behind, and were forced to surrender to the Germans. Despite the intensity of the fighting, German losses were between 3,000 and 4,000 men, a far smaller number than that of the defenders.

36

In order to complete their control of the Baltic, the Germans needed to seize the large islands off the Estonian coast, where a substantial Soviet garrison force had established itself. The German operation, codenamed

Beowulf

, commenced on 8 September, with landings by the reinforced 61st Infantry Division on Vormsi, Saaremaa and Muhu. Fighting continued until 5 October. On 12 October, elements of 61st Infantry Division landed on the last remaining island, Hiiumaa. The defenders fought on until 21 October. The Germans lost a little under 3,000 men; the entire Soviet garrison of over 23,000 men was lost, with nearly 5,000 killed and the rest captured.

The campaign to seize the Baltic States was over. With the exception of the Estonian islands, operations were complete with the fall of Tallinn at the end of August, barely two months after the beginning of hostilities. Stalin had seized the three states partly in order to protect Leningrad; this aim has to be seen as a failure. If Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania had continued as independent nations, it is likely that it would have taken the Wehrmacht at least as long to seize them, whether this were achieved by diplomatic pressure or by force of arms, and the Red Army could have used the intervening weeks to prepare itself better for battle. Instead, the frontier armies were annihilated, and the battered remnants would now have to fight on the outskirts of Leningrad itself. In the Baltic States, as the smoke and dust of battle dispersed, everyone – Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians and their German occupiers – looked to see what the future held for the three countries.

THE BALTIC HOLOCAUST

The nations involved in the Second World War entered the conflict at different points in time. In almost every case, the main emotions that the population felt on their entry into the war were fear or consternation. For many in the Baltic States, though, the initial reaction was very different, as one Lithuanian recorded: ‘It struck Lithuania like a clap of thunder: WAR. What joy, WAR. People met and congratulated each other with tears in their eyes. Everyone felt that the hour of liberation was near.’

1

As the Germans marched into Lithuania, they were greeted by jubilant crowds, and thousands of people who threw bunches of flowers to the men they regarded as their saviours from the Bolsheviks. One observer noted that red blooms were conspicuously absent from the bouquets.

2

But whilst many Lithuanians celebrated, the reaction of Lithuania’s Jewish community was very different: ‘Although crowds of Lithuanians greeted the Germans with flowers, it was no surprise that we closed our shutters, lowered our curtains, and locked ourselves up in our homes.’

3

Neither of these reactions was particularly surprising, given the events that had occurred in the Baltic States; similar sentiments were evident in Latvia and to a lesser extent – not least due to the very small Jewish population – in Estonia. The reactions showed a fundamental difference between Jewish and non-Jewish communities in their response to the German invasion; but the differences between the two communities ran far deeper, and would be exploited ruthlessly by the Germans. A few weeks before the onset of

Barbarossa

, a farmer in the Lithuanian town of Plungė was heard to remark: ‘The Germans only have to cross the border, and on the same day we will wade in the blood of Jews in Plungė.’

4

The history of anti-Jewish pogroms is a long one, stretching back at least as far as the Alexandrian Empire. Throughout the 19th century, there were repeated attacks on Jews in most of Europe, and given the large concentration of Jews in Poland and the Russian Empire, it was inevitable that these areas would see the greatest number of aggressive incidents. Remarkably, given the large Jewish population of Latvia and Lithuania, there was relatively little anti-Jewish violence in the Baltic States, compared with other parts of the Czar’s empire. In Lithuania, there was certainly widespread hostility at various levels, but this was little different from other Catholic countries, and violence to persons or property was unusual. The hostility towards Jews exemplified by the above quote, therefore, is all the more striking.

As has been discussed, there was a widespread perception in Lithuania and Latvia that the Jews were active supporters of the Soviet occupation. From the point of view of the Jews, there was little apparent choice. Whilst many – perhaps even most, given that Jews were strongly represented amongst the business classes – would have preferred to have been allowed to continue living their lives in Lithuania and Latvia as they had done for much of the century, the division of Europe into spheres of influence by Germany and the Soviet Union left no room for such dreams. If the Baltic States were to be forced into either the Soviet or the German camp, the Jews had to choose the former. Although the Final Solution had not yet been devised or implemented, the treatment of Jews in territories controlled by Germany was well known, and if there were any doubts, the flood of Jewish refugees from Poland into Lithuania in 1939 dispelled them. An additional factor that resulted in many Jews seeking employment with the new communist authorities was that before the Soviet occupation, most Jews worked in private firms. The nationalisation of these firms left many of them unemployed, and given the lack of job opportunities elsewhere, they took whatever employment they could get from the new governments. Nevertheless, in the interests of balance, it must be pointed out that the Jewish populations of Lithuania and Latvia formed a disproportionately large percentage of the membership of communist and pro-communist organisations even prior to the Soviet occupation.