Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (34 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Missouri governor Crittenden offered five thousand dollars for the arrest and conviction of the men who had robbed two trains—but offered double that reward each for Frank and Jesse James.

In early September 1881, the James Gang, now including newcomer Charley Ford, flagged down a St. Louis, Alton & Chicago Railroad train as it slowed to go through an area known as the Blue Cut in Glendale, Missouri. Although five of the robbers were masked, Jesse James was not and actually told passengers who was holding them up. The train’s safe was almost empty, so the gang relieved the passengers of their money, watches, and jewelry, fleeing with about a thousand dollars. As it turned out, this was Jesse James’s last robbery.

That ten-thousand-dollar reward stirred up a lot of interest. Jesse was no longer that larger-than-life character whose name alone evoked terror. Realizing that there were now few people he could trust, Jesse settled with his family in St. Joseph, Missouri, living there under the name of Thomas Howard.

To keep his gang close, Jesse let Charley and his younger brother Bob Ford stay with him. The rest of his gang was scattered nearby: His cousin Wood Hite was staying with another gang member, Dick Liddil, at the home of Charley Ford’s sister Martha Bolton. Apparently Martha was a lovely woman, as both Hite and Liddil were said to be smitten with her. There were even some reports that Jesse also had cast his eyes in her direction. But something happened in that house in early December. There already was some bad blood between Hite and Liddil about the split on the Blue Cut job, but the tension erupted one morning and they

took to shooting at each other. Both men were wounded, but probably not seriously. Then Martha and Bob Ford came upon the scene, and the twenty-one-year-old Bob Ford shot Hite once in the head, settling the dispute. Jesse James’s cousin was buried in a shallow grave on the property. Liddil and Ford knew they had a serious problem: No one wanted to hazard a guess at what actions Jesse might take when he learned his cousin had been killed.

Robert Ford was twenty years old when he shot unarmed Jesse James in the back of the head. He later reenacted the deed onstage in the play

How I Killed Jesse James

—but most people condemned his cowardly action and the play failed.

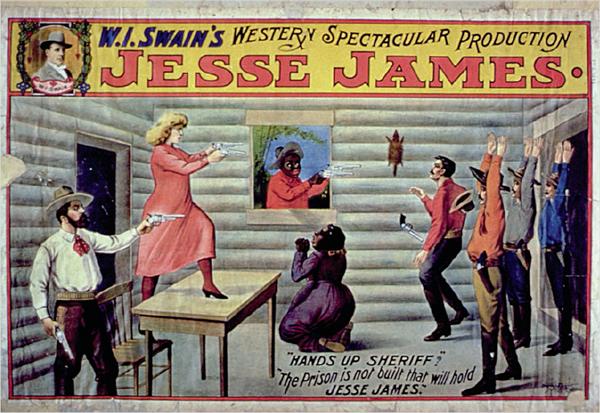

In death, Jesse James’s celebrity grew. Only Buffalo Bill appeared as a hero in more dime novels, in addition to numerous “true accounts” and even touring stage shows.

Charley and Bob Ford were looking for a way out of this mess, and in January they found it. They met secretly with Governor Crittenden and the Clay County sheriff and were not at all surprised to discover they shared some goals, the foremost of which was to rid Missouri, and perhaps the world, of Jesse James. In addition to the ten-thousand-dollar reward, the Ford brothers wanted a blanket pardon for all their crimes, including the murder they were about to commit, as well as a pardon for Liddil. The governor apparently was amenable, although the extent of that amenability would later be debated. Several days later, Liddil surrendered to the sheriff, although no announcement was made to the press so as not to alert Jesse.

Sometime in March 1882, Jesse began planning his next stickup, finally deciding to rob the bank in Platte City, Missouri. To pull it off, though, he told Charley Ford, he needed some other people. Ford suggested his brother Bob. Preparations were stepped up in late March. The robbery was planned for the first week in April.

At breakfast on the morning of April 3, Jesse was surprised to find an article in the local newspaper reporting that Liddil had surrendered. Word had leaked out. Oddly, he didn’t ask the Ford brothers if they knew anything about this, a natural question, and the fact that he didn’t ask made them very nervous. Instead, he cursed Liddil as a traitor and declared that he deserved to hang. After breakfast, Jesse had some chores to do. It was a warm day, so he took off his coat. Jesse always wore his guns, but he also wore a coat so no one would wonder why a peaceful man named Tom Howard was carrying two six-shooters. When he took off his coat, he also took off his gun belt and laid his guns on the bed. This was very unusual for him, as he was never to be found without his guns at arms’ length. It was the opportunity the Fords had been waiting for. As they were talking, Jesse suddenly noticed that a picture hanging on the wall was askew and did something completely out of character. He stood on a chair, turned his back to the Fords, and started straightening the picture, or dusting it.

Bob Ford shot him dead. Both Ford brothers had pulled their weapons; there were reports that Charley fired too and missed. But Bob Ford’s one shot hit Jesse James under his right ear, and he fell. He was thirty-four years old when he died.

Bob Ford sent wires to the governor and the sheriff, claiming the reward, then both brothers surrendered to the local marshal. As word spread that Thomas Howard was actually the feared killer Jesse James, the people of St. Joseph rushed to the house to catch a glimpse of his body, stunned to discover that the most wanted man in the country had been living comfortably among them.

The assassination of Jesse James made national headlines. The popular

Police Gazette

immediately published this fanciful illustration (

above left

). The photo of the outlaw in death became a national sensation, and crowds flocked to see the house in St. Joseph where he was murdered.

This softcover edition from Chicago’s Stein Publishing House was typical of the numerous books rushed into print after James’s murder.

The Fords were arrested. Two weeks later, within hours, both men were indicted for the murder of Jesse James, pleaded guilty, were sentenced to hang, were pardoned by Governor Crittenden, and walked out of the prison free men. Rather than the ten-thousand-dollar reward, they ended up with about six hundred, as the governor divided the money among many deserving parties—himself included. And, rather than being acclaimed for finally bringing Jesse James to eternal justice, the Fords were scorned as cowards for shooting him in the back.

Within a month of Jesse’s death, the newspaperman John Edwards began corresponding with the governor to arrange Frank James’s surrender. For the next three years, Frank fought

charges accusing him of committing numerous crimes in several states. He was tried on only two of the murder-robberies and was acquitted. Many respectable men testified to his good character. In February 1885, he was cleared of all charges. For him, the Civil War and all the battles that followed finally were over.

Charley and Bob Ford toured in a theater production entitled

The Brother’s Vow; or, the Bandit’s Revenge,

in which they reenacted the murder of Jesse James. Initially it was quite successful, but over time audiences lost interest, and it closed, leaving them almost broke. In 1884, Charley Ford, addicted to morphine and suffering from tuberculosis, and distraught at being considered a coward, committed suicide. Bob Ford held several jobs, earning some money posing for photographs with rubes in dime museums, billed as “the man who killed Jesse James.” By 1892, he was running a tent saloon in Creede, Colorado. A man named Ed O’Kelley shot and killed him there after an argument.

Frank James held several jobs, even touring with Cole Younger for a bit in a theatrical production called

The Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West Show.

Frank James died of a heart attack in 1915.

The legend of Jesse James has been told in almost every American cultural medium—but two often-asked questions have never been satisfactorily answered. One: Was Jesse James a hero of the Old South, fighting against the evils of Reconstruction and the carpetbaggers’ intent to profit from the destruction of war, or was he an outlaw who took advantage of the political situation? When he raged, “Just let a party of men commit a bold robbery, and the cry is hang them, but [President] Grant and his party can steal millions, and it is all right,” was he simply an actor playing a role created for him by John Edwards, or did he really mean it? The answer, most probably, is a bit of both. He started out with a set of skills perfected in the war; then he clearly embraced and enjoyed playing the noble character fighting for Southern dignity, and perhaps at times he truly meant it. But even after that was no longer relevant, he continued robbing and killing. He knew no other way.

The second and equally intriguing question is, Why would he take off his guns and turn his back on two men he did not know especially well and probably didn’t trust? He never went anywhere without his guns. Historians have offered a variety of explanations, describing the act as everything from foolhardy to courageous. Bob Ford once said he thought it was a trick: that Jesse wanted to make it appear that he trusted them so that he might later take action against them. Others have suggested that perhaps Jesse was tired and careless and willing to let fate play its hand. As he himself once wrote, “Justice is slow but sure, and there is a just God that will bring all to justice.”

DOC HOLLIDAY