Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School and Billy Bunter's ... (3 page)

Read Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School and Billy Bunter's ... Online

Authors: Frank Richards

CHAPTER V

BY WHOSE HAND?

“HE, he, he!”

“Hallo, hallo, hallo! What’s the joke, old fat man?” Billy Bunter did not

answer that question. But he grinned—a grin so wide, that it extended from one

of Bunter’s fat ears to the other. A good many eyes turned on the Owl of the Remove.

Bunter, evidently, was in possession of a joke—a great joke—a joke that made

him quite hilarious.

It was morning—and the Remove had been out in break. Now they were gathering at

the form-room door for third school. Billy Bunter, as a rule, was among the

last to arrive: punctuality had never been one of Bunter’s weaknesses. On this

occasion, he was among the first.

And he was chuckling and grinning. Something was stirring him to merriment,

though the other fellows were quite in the dark as to what it was.

“The jokefulness seems to be terrific,” remarked Hurree Jamset Ram Singh. “What

have you been up to, my esteemed and fatheaded Bunter?”

“Oh! Nothing!” answered Bunter. “It wasn’t me.”

“What wasn’t you?” asked Johnny Bull.

“Oh! Nothing! Quelch may be going to get a surprise —or he may not! I don’t

know anything about it, of course,” said Bunter, astutely. “I’ve been standing

here a long time—practically all through break. So if any fellow got in at the

form-room window, it couldn’t have been me, could it?”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“You howling ass,” said Peter Todd. “What did you get in at the form-room

window for?”

“I’ve just told you I didn’t,” snapped Bunter. “Look here, Toddy don’t you get

making out that I’ve been anywhere near the form-room window. If Quelch heard,

he might think that it was me.”

“That what was you?” asked Harry Wharton.

“Oh! Nothing!”

“You’ve been playing some potty trick in the form-room?” asked Bob Cherry.

“No!” hooted Bunter. “I haven’t been in the form-room. So far as I know, the

window wasn’t left open, and if it was, I never climbed in.”

“You jolly well couldn’t,” said Skinner. “Too much to lift.”

“Of course I couldn’t, without a bunk up,” agreed Bunter. “And Dabney of the

Fourth never gave me a bunk up, either.”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“What has that frumptious fathead been up to?” asked Frank Nugent. “Didn’t

Quelch give you enough in his study yesterday? Asking for more?”

“I haven’t been up to anything. If Quelch gives a fellow six, Quelch must

expect to hear what a fellow thinks of him,” said Bunter. “I couldn’t sit down

to prep last evening. But I haven’t done anything, of course. If Quelch gets a

surprise when he goes into the form-room, I don’t know anything about it. How

could I, when I haven’t been in the form-room in break?”

“It was something with chalk in it,” said Vernon-Smith with a chuckle.

Bunter jumped.

“Chalk! How do you know, you beast? I haven’t touched any chalk. Don’t you get

saying I’ve had any chalk—!

“Don’t you want Quelch to know you’ve been handling chalk?” chuckled the

Bounder.

“No fear! He might think I’d chalked on the blackboard! You know what a

suspicious beast he is—.”

“Then you’d better wipe the clues off your waistcoat, old fat bean.”

“Ha, ha, ha!” yelled the juniors, as Billy Bunter cast a startled blink

downward at his extensive and well-filled waistcoat. On that garment were

several smudges of chalk—which leaped to all eyes excepting Bunter’s.

“Oh!” gasped Bunter. “I—I hadn’t noticed that! I say, lend me your

handkerchief, Wharton—I’d better rub that off.”

“Eh! Can’t you use your own hanky?” asked Harry.

“Well, I don’t want to make my hanky all chalky. Lend me yours, quick, old

chap. Quelch may be coming any minute. Look here, will you lend me your hanky

or not, Wharton?”

“Not!” answered the captain of the Remove, laughing.

“Beast! Lend me your hanky, Toddy.”

“I’ll watch it!” said Peter Todd.

“Beast!”

Billy Bunter extracted his own handkerchief from his pocket, and hurriedly

wiped away the traces of chalk. The chalky handkerchief was jammed back into

his pocket. He cast an anxious blink along the corridor: but Quelch was not yet

in sight, and the fat Owl breathed more freely. The tell-tale clues were gone.

“So you’ve been chalking something on the blackboard in the form-room, you fat

ass?” asked Hazeldene.

“Nothing of the kind, Hazel. Somebody may have,” said Bunter. “After all, lots

of fellows think Quelch a beast, don’t they? Somebody may have chalked it on

the blackboard, for all I know. He, he, he! It wasn’t me. Of course, I trust you

fellows—I know you wouldn’t give a man away. But you can’t be too careful,

with Quelch. So I never did it, see?”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“You utter ass,” said Harry Wharton. “If you’ve chalked anything of that kind

on the blackboard, Quelch will go off at the deep end.”

“He, he, he! Let him! He won’t know who did it!” chuckled Bunter. “I never

signed my name to it, you know! He, he! Besides, I never did it! I say, you

fellows, fancy Quelch’s face when he sees it on the blackboard. He will know

what the Remove thinks of him, what?” Bunter chuckled again. “I say, he will be

wild! He will guess it was a Remove man—but he won’t know which man it was. I

can tell you fellows, I’m fed up with Quelch! What do you think he said to me

in his study yesterday? He said I was untruthful!”

“Did he?” gasped Bob Cherry. “Now what could have put that idea into his head?”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“You can cackle,” said Bunter, warmly. “I call it insulting. I know you fellows

ain’t so particular as I am in things like that, but did you ever know me tell

a lie? I ask you!”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“Hallo, hallo, hallo! Here comes Henry!” murmured Bob.

Mr. Quelch appeared at the corner of the corridor. He gave the assembled

juniors a sharp glance, and Bob wondered, for a dismayed moment, whether his

keen ears had caught the word “Henry”. However, the Remove master rustled up

the passage to the door on the form-room, and unlocked the same to admit his

form. The Remove marched in and took their places. Mr. Quelch went to his high

desk.

The blackboard, which had been used in second school, stood on its easel facing

the form. What was chalked on it was, therefore, visible to all the Remove, but

not, for the moment, to their form-master.

All eyes turned on the blackboard. Then there was a sudden gust of laughter.

The Removites really could not help it. After what Bunter had said, they

expected to see something chalked on the blackboard which was calculated to

make Quelch “wild”, What they saw was an inscription in large capital letters:

QUELCH IS A BEEST!

“Ha, ha, ha!” woke the echoes of the form-room. Billy Bunter grinned—a wide

grin. Bunter was quite pleased by this tribute. All the Remove were

laughing—that inscription on the blackboard seemed to have taken them by storm.

But Quelch wouldn’t laugh when he saw it—Quelch would be in a fearful rage—all

the more because there was no clue to the writer!

“Ha, ha, ha!” roared the Remove.

“He, he, he!” cachinnated Bunter.

Mr. Quelch stared at his form, with knitting brows. That outburst of merriment

took him by surprise, and did not please him.

“Silence!” he thundered. “What is the meaning of this? What—?” He realised at

once that the blackboard was the cynosure of all eyes, and guessed that there

must be something unusual on it. He whisked round the blackboard to see what

had caused that burst of hilarity.

The laughter died away quite suddenly. Quelch’s expression, as he looked at the

chalked words on the blackboard, did not encourage merriment. For a moment, Mr.

Quelch stared at it: then he turned to his class.

“Bunter!” His eyes fixed on the Owl of the Remove.

“Oh, crikey!” gasped Bunter, in alarm.

Why Quelch picked on him was an absolute mystery to the Owl of the Remove.

There was nothing, so far as Bunter knew, to give the remotest clue to the writer

of that inscription. He had not expected for a moment that the gimlet-eyes

would fix on him. But they did.

“Bunter! You have done this!”

“I—I wouldn’t, sir! I—I don’t think you’re a beast, sir, like the other

fellows—.”

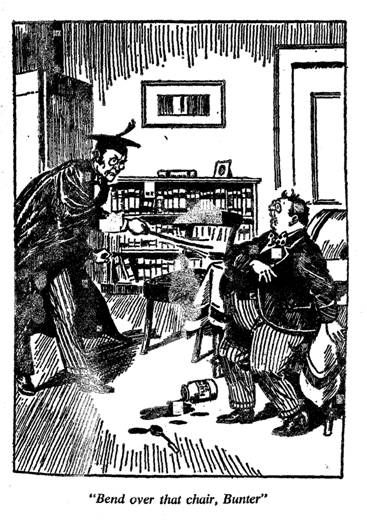

“Bunter!” thundered Mr. Quelch. “You wrote this! It was you, Bunter, who

chalked this—this unexampled impertinence on the blackboard! Bunter, you

entered the form-room surreptitiously during break—by the window—.”

“Oh, lor’! I—I never knew you saw me, sir!” groaned Bunter. “I—I thought you

were in your study—oh, scissors!”

“I did not see you, Bunter.”

“Oh! Then—then I didn’t do it, sir! I—I was in the tuck-shop at the time—Mrs.

Mimble was serving me with a jam-tart, sir, at the very minute I was chalking

on the blackboard—I mean when I—I wasn’t chalking on the blackboard—.”

“I shall not cane you again, Bunter,” said Mr. Quelch, breathing hard. “You

will be detained for the half-holiday this afternoon. I shall set you a

detention task, and you will remain in the form-room until you have finished

it—.”

“But—but I never—!”

“Silence!” almost roared Mr. Quelch.

Billy Bunter quaked into silence. Mr. Quelch took a duster and wiped the

blackboard. Third lesson began in the Remove in rather an electric atmosphere.

Billy Bunter sat with a fat face of woe. He was booked for the afternoon—and he

knew, from experience, what Quelch’s detention tasks were like! Why Quelch had

picked on him, he did not know. It seemed like magic to Bunter. It was one more

proof that Quelch was a “beest”.

CHAPTER VI

NOT WANTED!

“HARRY,

old chap—!”

Harry Wharton shook his head.

“Sorry!” he said.

“Eh!” Billy Bunter blinked at the captain of the Remove, in the doorway of the

changing-room, in surprise. “What are you sorry about?”

“Shortage of cash,” explained Wharton. “Nothing doing! Try Smithy.”

“If you think I want to borrow anything from you, Wharton—!” said William

George Bunter, with a great deal of dignity.

“Don’t you?”

“No!” roared Bunter. “I don’t!”

“Then why did you call me old chap?’ inquired the captain of the Remove.

“Beast! I—I mean, dear old fellow—!” said Bunter, hastily.

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“I say, I’m booked for this afternoon,” said Bunter, dismally. “I’ve got to go

into the form-room at two, and Quelch is going to give me a paper to do—I

shouldn’t wonder if it’s deponent verbs—it would be like him! And you fellows

are going to play cricket! Now look here, Harry, old chap, we’ve always been

pals, haven’t we?”

“Have we?” asked Harry Wharton, in surprise. “First I’ve heard of it.”

“Oh, really, Wharton! Who was it stood by you, and helped you through, and all

that, when you were a new fellow here?” demanded Bunter.

“Nugent!” answered Harry, laughing.

“You don’t remember what I did for you?” asked Bunter, sarcastically.

“Yes, I do. You borrowed half-a-crown the first day. And that reminds me that

you’ve never squared. What about it?”

“I wish you wouldn’t talk rot,” said Bunter, peevishly. “After all I’ve done

for you, you might do a little thing for me. I want to play cricket this

afternoon. You know how keen I am on the game—.”

“Oh, quite!” agreed Harry. “Very keen, when you want other fellows to do your

lines. Not at other times.”

“Well, I’m frightfully keen now,” declared Bunter. “I suppose you’ve made up

the eleven to play the Fourth this afternoon?”

“Sort of,” said Harry, laughing. “As we’re due on Little Side in ten minutes, I

shouldn’t be likely to leave it very much later.”

“Well it’s not too late to make a change in the team!” suggested Bunter.

“You’re not much of a judge of a man’s form, old fellow, and I’m blessed if I

know why the fellows made you skipper: but you’ve got sense enough to leave out

a dud and put in a better man if you can get one, what?”

“Oh, quite. Where’s the better man?”

“Here! Now, if you go to Quelch and explain that you simply can’t leave me out,

because it’s a pretty tough match, Quelch will let me off detention, see? I

specially want to go down to Friardale this afternoon—I mean, I specially want

to play cricket—being awfully keen on the game, you know. I don’t want to go

down to Friardale because Uncle Clegg’s got jolly good ices—nothing of the

kind. I’m fearfully keen on cricket. Easy enough to make room for me in the

team—you can leave out Cherry— he’s not much good.”

“Hallo, hallo, hallo! Who’s not much good?” roared Bob Cherry.

“You, old chap! Look at the way you bat!” argued Bunter. “Or there’s Toddy—no

good at all, if you don’t mind my mentioning it, Toddy.”

Peter Todd gave his fat study-mate an expressive look, but no other reply.

“Or there’s Squiff—or Browney—or Inky—or Nugent—or Bull—or Smithy,” went on

Bunter. “What about dropping Smithy? I daresay he’d rather hike along to the

Cross Keys for a smoke, than play cricket, if you come to that. Wouldn’t you,

Smithy?”

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“The fact is, I don’t care whom you leave out, so long as you put me in, Harry,

old chap. That’s the important point. Quelch will be sure to let me off, if you

tell him I’m wanted—he wouldn’t spoil a Form game by detaining the best

cricketer in the Remove—!”

“Ha, ha, ha!” yelled the Remove cricketers.

“Well, you fellows know how I play,” argued Bunter. “There’s a lot of jealousy

in cricket, and I never have a show—but facts are facts, all the same. If

Wharton knew a man’s form, he would pick me out for the Highcliffe match when

it comes off—not that I expect him to!” added Bunter, bitterly. “As I said, I’m

used to jealousy. But it’s really important this afternoon. Wharton, because I

want to go down to Uncle Clegg’s—I mean to Little Side. Look here, old chap,

leave out any man you like,” said Bunter, in a burst of generosity. “Only put

me in, see?”

“I see,” assented the captain of the Remove, “and now, if you’ve finished your

funny turn, roll away, old barrel.”

“You won’t play me?” demanded Bunter.

“Not at cricket, old fat bean. When we play the Fourth at marbles or

hop-scotch, I’ll think of you.”

“Beast! I mean, look here, dear old fellow, I’ve got to get off detention. Just

go to Quelch and tell him that I’m wanted in the game this afternoon—!”

“But you’re not wanted.”

“Oh, really, Wharton! I wish you’d keep to the point,” said Bunter, peevishly.

“The point is, to get me off detention. See? Quelch won’t notice that I’m not

in the game—why should he? If he did, you could tell him I’ve been taken

suddenly ill, see? How’s that?”

“Out!” said Wharton.

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“Beast!” roared Bunter. “I tell you, I don’t want detention this afternoon—I’d

rather play cricket than do deponent verbs—!”

“What a jolly good reason for picking a man for a match!” remarked Bob Cherry.

“Ha, ha, ha!”

“Now you’ve finished, Bunter—!”

“I haven’t finished—!”

“Yes, you have! Give him a prod with your bat, Johnny.”

“Yoo-hooop!” roared Bunter, as Johnny Bull’s bat established contact, and he

departed from the doorway in haste.

There was no cricket for Bunter that afternoon—even though he did indubitably

prefer cricket to deponent verbs!

The fat junior rolled away in an indignant and morose frame of mind. It was

true that Bunter was thinking more of the ices at Uncle Clegg’s tuck-shop in

the village of Friardale, than of the great summer game. He had borrowed

half-a-crown from Lord Mauleverer specially to be expended on those ices. It

was a moral impossibility to sit in the form-room grinding at a detention task,

with Mauly’s half-crown burning a hole in his pocket, and those delicious ices

waiting for him at Friardale,

Billy Bunter suddenly made up his fat mind, and rolled away towards the gates.

He resolved to chance it with Quelch. Two o’clock was striking from the

clock-tower, at which hour he was due for detention: so there was no time to

waste. Bunter rolled away from the House: and, like Iser in the poem, he rolled

rapidly.

He eyed Gosling uneasily, as the ancient porter of Greyfriars, in the doorway

of his lodge, glanced at him.

If Gosling knew that he was under detention, Gosling was quite capable of

stopping him at the gate—that was the sort of brute Gosling was!”

But Gosling, apparently, did not know: at any rate, Billy Bunter passed under

his ancient eyes unchallenged. He reached the old arched stone gateway, where

the gates stood wide open on a half-holiday, And there, for a moment, Billy

Bunter hesitated—and halted.

Billy Bunter was not, perhaps, very bright. But he was bright enough to realise

that “chancing it” with Quelch was a risky business. He could explain to Quelch

that he had forgotten all about his detention—forgotten it so utterly that his

mind was a perfect blank on the subject. But he had a deep misgiving that

Quelch would not believe him, Often and often had Quelch doubted Bunter’s word,

and Bunter felt that he could not expect any improvement in Quelch in that

respect.

If he “cut” detention, there would be a row. Quelch, as usual, would be a

beast. And Billy Bunter, with a lingering glimmer of common-sense, hesitated to

draw once more the vials of wrath upon his fat head.

He hesitated—but it is well said that he who hesitates is lost. On the one

hand, were delicious ices at Uncle Clegg’s—on the other, a dismal detention

task with deponent verbs in it very likely. Billy Bunter rolled out of gates,

and took the lane to Friardale.

And as Bunter rolled out of gates, Henry Samuel Quelch looked out of the big

window in the form-room corridor. Quelch, who was as regular as clockwork, had

arrived at the door of the Remove form-room as two o’clock struck—with a

detention paper in his hand, and a grim expression on his face. He was ready to

let Bunter into the form-room, and see him started on that detention

paper—which, as the fat Owl dreaded, had deponent verbs in it! Quelch was ready:

but Bunter, like Ethelred of old, was unready!

Bunter was not to be seen—till Quelch looked from the window, expecting to see

him loitering on his way to the House—and even Quelch did not expect a fellow

to be keen and eager for detention on a summer’s afternoon.

But he did not see Bunter loitering—he beheld, in the distance, an unmistakable

fat figure rolling out of the gates. Quelch stared at that fast figure as it

disappeared. His grim face grew grimmer, and his gimlet-eyes gleamed. Bunter,

due for detention, was walking out of the school—as if free as a bird that

afternoon.

“Upon my word!” breathed Mr. Quelch.

Two or three minutes later, Henry Samuel Quelch, complete with hat and

walking-stick, was striding down to the gates. Billy Bunter’s prospect of ices

at Uncle Clegg’s that afternoon was after all, doubtful!