Birthnight

by Michelle

Sagara

Rosdan Press, 2011

Toronto, Ontario

Canada

SMASHWORDS EDITION:

978-1-927094-14-3

Copyright 2011 by Michelle Sagara

All rights reserved

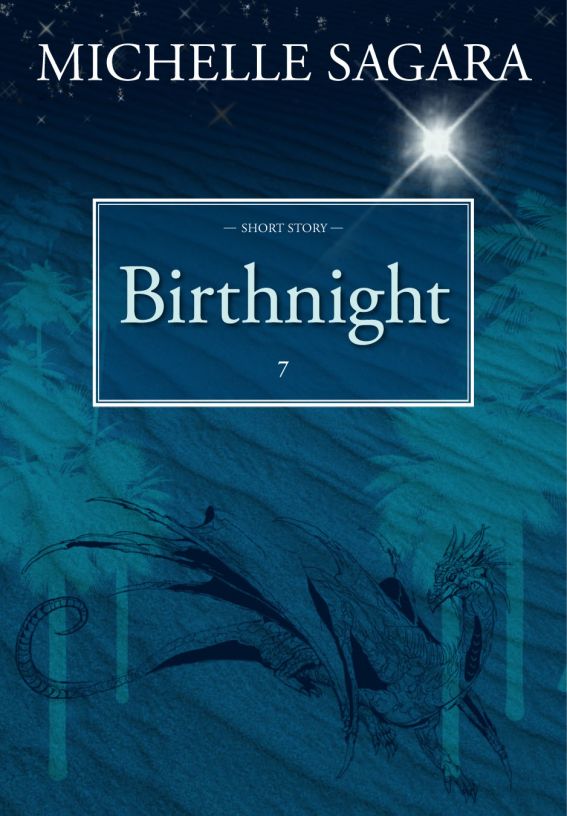

Cover design by Anneli West,

Four

Corners Communication

Dragon: photoshop brush by Rob

Marks/Breezy.com

Palm trees: photoshop brush by

horhewbrushes.com

“Birthnight” Copyright 1992 by Michelle

Sagara. First appeared in

Christmas Bestiary

, ed.

Rosalind M. Greenberg and Martin H. Greenberg.

Introduction Copyright 2003 by Michelle

Sagara. First appeared in

Magical Beginnings

ed. Steven

H. Silver and Martin H. Greenberg.

Smashwords Edition License

Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to

other people. If you would like to share this book with another

person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you

share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it,

or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return

to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for

respecting the author's work.

Novels by Michelle

Sagara

The Book of the Sundered

Into the Dark Lands

Children of the Blood

Lady of Mercy

Chains of Darkness, Chains of Light

Chronicles of Elantra

Cast in Shadow

Cast in Courtlight

Cast in Secret

Cast in Fury

Cast in Silence

Cast in Chaos

Cast in Ruin

Cast in Peril (September 20, 2011)

The Queen of the Dead

Silence*

Touch**

Grave**

*Forthcoming in 2012

**Forthcoming

Memory is a tricky thing. When I decided I

would reprint all of my short stories as individual ebooks, I also

decided I would take the time—and space—to write introductions for

each of the stories. But

Birthnight

had been reprinted

once, in 2003, for a collection of first stories by various

authors. So I already had an introduction for the short story.

Except, rereading it, there are things I don’t remember, in 2011,

the way I did in 2003.

Other things have changed. I am not,

obviously, working on the fifth book of

The Sun Sword

now. I

am, on the other hand, working on the fifth book of

House

War

now, and I thought that would be two books too, and I am

reading a new Tanya Huff novel, one chapter at a time—and Tanya

actually doesn’t write

quickly

when a book is being read

that way—so I guess the more things change, the more they stay the

same. I’ve been nagging her. I did that back in 1990 as well, but

it was easier as she was in the store thirty-six of the same hours

a week as I was.

“Birthnight” was the first short story I

sold. It’s not the first short story published—that was “Gifted”,

because they moved the anthology which contained it up a month to

coincide with the Disney Aladdin movie that was being released that

month. But I was probably more nervous and more worried about

“Birthnight” than I was about the novel which would see print in

the same month.

I wrote this story twenty years ago. It has

some of the wildness and some of the sense of elegy that I feel I

absorbed from the books I loved in my childhood—

Lord of the

Rings, Forgotten Beasts of Eld

—and while it is not the story I

would write today, I can honestly say I still see the heart of it

clearly.

Toronto, August 2011

------

There are a number of loosely related facts

that underpin the writing of this story. First: I love Christmas

stories. The story of Santa Claus, the jolly, white-bearded

whimsical gift-giver, coupled with the certain knowledge that my

parents had lied to me, deliberately about his existence, is

probably chiefly responsible for the way that love is expressed;

there is both giving and losing, gift and loss, inherent on the

occasion.

Second: Although I’m not what anyone rational

would call a religious person, there’s a certain element of

Christian myth that I find fascinating, in almost the same way that

I find Tolkien fascinating; it speaks to me in a way that

resonates, that feels true, and that I rationally would never

defend as reality, no matter how much it can inform my own.

Third: When this story was written, I knew

almost nothing about the short story market, because my first

attempt at a short story was what eventually became the

Hunter’s Oath

and

Hunter’s Death

duology; my

third attempt was what eventually became the four book

Books of

The Sundered

tetralogy. Just for the record, I originally

thought that the

Sun Sword

series, of which I am currently

working on volume five, would be two novels—so I admit up front

that I don’t always understand the concept of “length” when it

comes to number of words. Mike Resnick, who had written more novels

than I, and vastly more short stories than I, and with whom I’m

never likely to catch up – and who has also won almost every award

known to man for the writing of those – informed me of the

anthology for which Birthnight was originally written—one which

Marty Greenberg was editing. He also had a lot of advice to offer,

and if I wasn’t afraid of embarrassing him with what is admittedly

my terrible memory, I’d probably attempt to reconstruct it all.

Suffice it to say that if it weren’t for Mike Resnick, this story

and most of the others over which he has no direct bearing, would

probably not exist.

Fourth: I was working with Tanya Huff when I

wrote this story. She had written a story for the same anthology a

month or two earlier, and as I pretty much got to read all of her

work before she submitted it – which was wonderful for short

stories because she handed me the whole thing at once, whereas with

novels it was one chapter at a time—and she likes to end her

chapters in a way that will “keep people reading”, but I digress—I

had actually read the story in question. It was, of course,

excellent, and had all of the earmarks of a Tanya Huff story: It

was funny, it made me sniffle in places, and it was completely

rooted in contemporary culture from beginning to end. So when I

realized that this fledgling story would be in the same book as her

story, I knew damn well that I wasn’t going to write a contemporary

piece. She laughed when I told her this. She laughs when I remind

her of it. But really, it was true, and it still is; I love her

writing, and it is just so different from mine that I always feel

nervous after finishing something she’s written because I know my

work won’t evoke the same response.

I was living in my first house, and the room

that I worked in—which was my office until my oldest son was born

-- was painted bright pink (a leftover gift from the previous owner

of said house—we had always intended to repaint that room, but we

had never gotten around to it, and in the end, my mother painted

that room pale blue while I was in the hospital delivering my first

child because she wasn’t going to condemn a child to that despised

and loathsome pink), and the story was written on a Mac SE30, and

it was many, many months before Christmas, but all of that story

came to me in a sitting, in a mad rush of messy words and the

emotions that come out of that particular time of year.

I tweaked it afterwards, of course, poking

and prodding it, and stripping out words so that I would actually

come in at the right length, but I was happy with the story as it

came out, and it was this story that I chose to read at

Harbourfront, when I was—as usual—petrified about having to do

anything in a public venue.

I really hope you like it.

Toronto, 2003

On the open road, surrounded by gentle hills

and grass strong enough to withstand the predation of sheep, the

black dragon cast a shadow long and wide. His scales, glittering in

sun-light, reflected the passage of clouds above; his wings, spread

to full, were a delicate stretch of leathered hide, impervious to

mere mortal weapon. His jaws opened; he roared and a flare of red

fire tickled his throat and lips.

Below, watching sheep graze and keeping an

eye on the nearby river where one of his charges had managed to

bramble itself and drown just three days past, the shepherd looked

up. He felt the passing gust of wind warm the air; saw the shadow

splayed out in all its splendor against the hillocks, and covered

his eyes, to squint skyward.

“Clouds,” he muttered, as he shook his head.

For a moment, he thought he had seen ... children’s dreams. He

smiled, remembering the stories his grandmother had often told him,

and went back to his keeping. The sheep were skittish today;

perhaps that made him nervous enough to remember a child’s

fancy.

The great black dragon circled the shepherd

three times; on each passage, he let loose the fiery death of his

voice—but the shepherd had ceased even to look, and in time, the

dragon flew on.

* * *

He found them at last, although until he

spotted them from his windward perch, he had not known he was

searching. They walked the road like any pilgrims, and only his

eyes knew them for what they were: Immortal, unchanging, the

creatures of magic’s first birth. There, with white silk mane and

horn more precious to man than gold, pranced the unicorn. Fools

talked of horses with horns, and still others, deer or

goats—goats!—but they were pathetic in their lack of vision. This

creature was too graceful to be compared to any mortal thing; too

graceful and too dangerously beautiful.

Ahead of the peerless one, cloaked and robed

in a darkness that covered her head, the dragon thought he

recognized the statue-maker from her gait. Over her, he did not

linger.

But there also was basilisk, stone-maker, a

wingless serpent less mighty than a dragon, and at his side, never

quite meeting his eyes, were a small ring of the Sylvan folk,

dancing and singing as they walked. They did not fear the

basilisk’s gaze; it was clear from the way they had wreathed his

mighty neck in forest flowers that seemed, to the sharp eyes of the

dragon, to be blooming even as he watched.

And there were others—many others—each and

every one of them the first born, the endless.

“Your fires are lazy, brother,” a voice said

from above, and the dragon looked up, almost startled, so intent

had he been upon his inspection. “And I so hate a lazy fire.”

No other creature would dare so impertinent

an address; the dragon roared his annoyance, but felt no need to

press his point. It had been a long time since he had seen this

fiery creature. “I was present for your last birth,” he said, “and

you were insolent even then—but I was more willing to forgive you;

you were young.”

“Oh indeed, more insolent,” the phoenix

replied, furling wings of fire and heat and beauty as he dived

beneath the dragon, buoying him up, “and young. My brother, I fear

you speak truer than you know. You attended my last birth—there

will be no others.”

The dragon gave a lazy, playful breath—one

that would have scorched a small village or blinded a small

army—and the phoenix preened in the flames. But though they played,

as old friends might, there was a worry in the games—a desperation

they could not speak of. For were they not immortal and

endless?

* * *

“They do not see me,” the unicorn said

quietly, when at last the dragon had chosen to land. The phoenix

alas, was still playing his loving games—this time with the

harpies, who tended to think rather more ill of it than the dragon

had. They screeched and swore and threatened to tear out the

swan-like fire-bird’s neck; from thousands of feet below, the

dragon could hear the phoenix trumpet.

“Do not see you? But sister, you hide.”

“I once did.” She shook her splendid mane,

and turned to face him, her dark eyes wide and round. “But now—I

walk as you fly, and they do not see me. I even touched one old

woman, to heal her of her aches—and she did not feel my presence at

all.”

Dragons are proud creatures, but for her

sake, he was willing to take the risk of exposing a weakness. “I,

too, am worried. I flew, I cast my shadows wide, I breathed the

fiery death.” He snorted; smoke cindered a tree-branch. Satisfied,

he continued. “But they did not even look up.”