Bittersweet (10 page)

Authors: Peter Macinnis

This drink, though it had the ill hap to kill one Negro, yet it has had the vertue to cure many; for when they are ill, with taking cold, (which they often are) . . . they complain to the Apothecary of the Plantation, which we call the Doctor, and he gives to every one a dram cup of this Spirit, and that is a present cure. And as this drink is of great use, to cure and refresh the poor Negroes, whom we ought to have a special care of, by the labour of whose hands, our profit is brought in; so it is helpful to our Christian servants too . . .

The distinction they made between their servants may seem an odd one, but Ligon explains even this:

Once I encountered a slave who wished to be a Christian, but on interceding with the slave's master, I was told that the people of the Island were governed by the Lawes of

England

, and by those Lawes, we could not make a Christian a Slave. I told him, my request was far different from that, for I desired him to make a Slave a Christian. His answer was, That it was true, there was a great difference in that: But, being once a Christian, he could no more account him a Slave, and so lose the hold they had of them as Slaves, by making them Christians; and by that means should open such a gap, as all the Planters in the Island would curse him.

To read the testimony of the planters, nothing was ever easy for them. That is one point at which Ligon was in complete agreement with later writers with the mindset of the plantation owner.

DERBY'S DOSE

The planter could make a good profit, but there was always the risk of bad weather, insurrection or war, not to mention death from disease (or taxes from a home government). The planter had to buy, clear and plant the land, buy Guinea grass for the animals, set up gardens for the slaves, and general working and living space. Purchases included tools, nails, hoops and staves for barrels, lime, cooking pots, building material, food for the slaves, equipment for the mill and boiling house, and then there were the skilled staff: even if these were slaves, they could still command extra allowancesâand many of them were free men, former indentured servants now out of their indentures.

The overseer, distiller, carpenter, drivers and wainmen, cooper, foreman sawyer, fireman, watchman, field-children's nurse, potter and âblack doctor' had all to be paid, as well as domestic servants. But above all, the slaves had to be fed, and while bought food was expensive, the food crops perversely needed the most cultivation just when the sugar needed harvesting!

The slaves were fed well enough at times, though for the most part planters tried to keep costs down by using local resources. The areas between cane plots could be planted with food crops, including such crops as yams, eddoes and bananas, brought from Africa by the slave ships. William Bligh's ill-fated breadfruit was one of the few failures; the slaves did not like the taste, and it was only well into the nineteenth century that people in the Caribbean began to eat it.

Hard physical labour requires protein, and sweaty work requires salt. It did not take long for the canny cod fishermen of New England to identify a new and not particularly fussy market. Their rejects, the badly split fish and fish with too much salt or not enough, could all be disposed of as âWest India cure', destined to feed the slaves. During the eighteenth century, in times of unrestricted trade, on average a ship would leave Boston every day for the West Indies, laden with reject fish. Around 1650, Richard Ligon saw that fish could be found closer to home, and he wrote in his

Exact History

:

As for the

Indians

, we have but few, and those fetcht from other Countries; some from the neighbouring Islands, some from the Main, which we make slaves: the women who are better vers'd in ordering the Cassavie and making bread, than the

Negroes

, we imploy for that purpose and also for making Mobbie; the men we use for footmen and killing of fish, which they are good at; with their own bowes and arrows they will go out; and in a dayes time, kill as much fish as will serve a family of a dozen persons, two or three dayes if you can keep the fish so long.

Other foods for the slaves varied from island to island. Jamaica had more free land than Barbados, enabling the slaves there to tend gardens where they grew food. Barbados was necessarily more dependent on outside sources, importing maize and rice from America and horse beans from Britain. Reliable figures are hard to come by, but one record exists of newly purchased slaves with no planted ground getting one fish and either nine plantains, two pints of rice or three pints of maize, each day. The food rations, it would seem, were minimal and monotonous, and might have accounted for the short working lives of most slaves.

During the sugar harvest there was cane to chew and syrup to drink, but by the end of the harvest the provision grounds were least productive. Thomas Thistlewood, an overseer in Jamaica in the middle of the eighteenth century, recorded signs of poor nutrition among the slaves in August and September, over a number of years. His diary for 25 May 1756, as quoted by Ward, reveals that a slave called Derby was caught eating the young canesâa definite offence, since it meant a reduced crop later on: âDerby catched by Port Royal eating canes. Had him well flogged and pickled, then made Hector shit in his mouth.' This treatment, referred to thereafter as âDerby's Dose', did not seem to deter the offender, who appears in Thistlewood's diary again in August:

Last night Derby attempting to steal corn out of Long Pond corn pieces, was catched by the watchman, and resisting, received many great wounds with a mascheat [machete], in the head etc. Particularly his right ear, cheek and jaw, almost cut off.

There is no record of what happened to Derby after that. It seems unlikely he survived, though. The excerpts from Thistlewood's journal quoted by Ward clearly reveal his care and consideration for those under his chargeâ when they weren't stealing food, that is. All sorts of odd punishments, including lockable masks of tinplate, were used to stop slaves eating the young cane. Wearing the mask was probably preferable to what happened to Derby. In some areas, the masks were also worn by kitchen slaves to stop them tasting the food they were preparing.

Forced to labour in the sugar mills from sunrise to late at night, it was inevitable that weary slaves would lose concentration and risk injury. The greatest danger came at the height of the season, when they were toiling away close to huge pans of sticky, scalding sugar juice, working for up to eighteen hours a day in fierce heat in the rush to deal with the huge masses of ripe cane that came in. Outside, the slaves who fed the cane into the rollers worked in cooler conditions, but they were just as much at risk of injury through being trapped by the rollers.

The three-roller mill was standard, and while some early ones were powered by humans, most were under animal, wind, water or steam power and slower to react to a human scream. A hatchet or cutlass was kept in a convenient place, ready to chop off the arm of any slave who was trappedâin order to save the slave's life. It made better economic sense to keep alive a slave with one arm, because that slave could still act as a watchman, clear blocked drains or guide the animals that did the heavy haulage.

While there is probably a degree of exaggeration in the tales the emancipists told later of slavery, it would be unwise to assume that the life of a slave was a pleasant one. The way slaves took advantage of unrest made this very clearâin fact, slaves were one reason not to fight wars in the Caribbean.

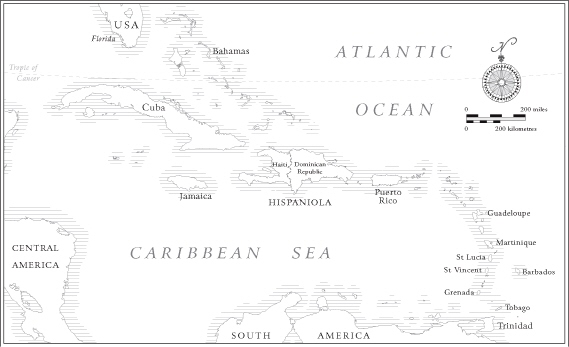

The territorial claims made by Spain and Portugal under the Treaty of Tordesillas could not be defended against the combined forces of the English, Dutch and French, and in the end Spain was forced during the seventeenth century to accept the presence of other powers in the Caribbean islands, just as Portugal had to accept the British and French in India and Africa, and the Dutch in the East Indies. In one case, the Spaniards shared the island of Hispaniola with the French.

Aside from anything else, whatever armed forces the Europeans had in the West Indies were needed there to maintain order in their own colonies. When the home nations went to war, extra forces would be sent in to attack and pillage the colonies and the shipping of the enemy, even though this caused unrest among the slaves.

TO DRIE APRICOCKS, PEACHES, PIPPINS OR PEARPLUMS

Take your apricocks or pearplums, & let them boile one walme in as much clarified sugar as will cover them, so let them lie infused in an earthen pan three days, then take out your fruits, & boile your syrupe againe, when you have thus used them three times then put half a pound of drie sugar into your syrupe, & so let it boile till it comes to a very thick syrup, wherein let your fruits boile leysurelie 3 or 4 walmes, then take them foorth of the syrup, then plant them on a lettice of rods or wyer, & so put them into yor stewe, & every second day turne them & when they be through dry you may box them & keep them all the year; before you set them to drying you must wash them in a little warme water, when they are half drie you must dust a little sugar upon them throw a fine Lawne.

Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book

, 1604

B

ryan Edwards, a planter and early historian of the West Indies, explained war in his neighbourhood like this:

Whenever the nations of Europe are engaged, from whatever cause, in war with each other, these unhappy countries are constantly made the theatre of its operations. Thither the combatants repair, as to the arena, to decide their differences.

According to Edwards, this was because the combatants who survived could make themselves rich. In the late eighteenth century, foreign navies plundered British merchant ships and kept the profits while Britain's navy made a treasure trove of the foreign trading vessels. But did the navies compensate the planters for their losses? Indeed they did not, the planters complained. The arena for their grudge matches was inevitably the lucrative Caribbean, but paying compensation to the planters would have eaten into their profits.

The warring navies chose the Caribbean, far from their home waters, for the rich cargoes carried in the area, and because of the way that prize money works in times of war, especially

The West Indies.

benefiting frigate captains whose ships were large enough to sail independently, and fast enough to run down almost any ship on the ocean. Edwards conceded that sometimes the British planters would gain, since Britain usually held the upper hand in privateering and blockading. This meant the French sugar trade was often badly affected, allowing English sugar interests a greater slice of the European market. At the same time, Royal Navy ships provided a ready market for rum, but the planters were not happyâit was not in their nature to be happy.

Prize money was paid for all ships and cargoes captured. It was divided in a complex manner, with larger sums going to the more senior officers, and many captainsâif they survived long enoughâbecame landed gentry in their later years. Frigates did best of all, because if a capture was out of the sight of the commanding admiral, the admiral's portion was also divided among the officers and crew.

Sometimes the naval officers were a bit greedy. Tradition has it that Josias Rogers, captain of the

Quebec,

was so impressed by the sight of a bullion-laden Spanish treasure ship, brought into Portsmouth during the Seven Years' War, that he determined to enter the navy and have a share in such riches. He did quite well from the War of American Independence, and settled on an estate in Hampshire, but when his banker failed and he lost half his fortune, Rogers just went back to sea to get some more. In the first five weeks of 1794 he took nine prizes, and estimated that his share of the proceeds would be £10 000.

The Royal Navy had taken more than 300 merchant ships in 1794, mainly American neutrals, in this legalised form of plunder. The prize courts later rejected half the claims on the ground that these neutral ships were sailing between neutral ports and not subject to seizure, but Captain Rogers and his crew still gained from three of their nine prizes. He later spent £3000 in contesting the lost cases, but Rogers did not enjoy his restored wealth for long, howeverâhe saw both his younger brother and nephew die of yellow fever before he succumbed to the same disease in 1795. There were rich pickings for those who survived, but many more lost their lives to disease.

The naval physician, Sir Gilbert Blane, found that in one year alone, 1779, England's West Indies fleet lost an eighth of its 12 019 seamen to diseaseâa total of 1518 dead, with another 350 ârendered unserviceable'. In 1794, the then Vice-Admiral Jervis' West Indies squadron lost about a fifth of its men to disease in just six months. The 89 000 soldiers of all ranks serving in the West Indies between 1793 and 1801 suffered 45 000 deaths, 14 000 discharged and 3000 desertions. Small wonder that British troops being sent to the West Indies were usually sent first to the Isle of Wight or Spike Island in the Cove of Cork, to prevent them deserting

en masse

. German and French mercenary units particularly objected to being sent to what they saw as certain death, and either deserted or mutinied at the prospect. While soldiers could also earn prize money, there was generally less to be had on land than on sea, and a much better chance of falling to disease.