Bittersweet (3 page)

Authors: Peter Macinnis

I turned my back on one of the last slave lines in the world, and walked back to the truck, with the sweat pouring off me. As I walked, I chewed on a piece of thick sweet sugar cane, a traditional New Guinea garden delicacy that one of the convicts had cut for me with the heavy, razor-sharp machetes they used. At the back of my mouth, the sweet juices commenced an attack that 40 years later would demolish a left molar tooth and leave me in a dentist's chair, musing about Shakespeare.

IN THE DENTIST'S CHAIR

Twenty years later, half the teak trees were thinned to make second-rate veneer, giving the other trees more room to grow. Another 20 years, and the mature logs were coming out of the plantation. At the same time, after half a lifetime's neglect, sugar cane and bad care had finally done for my molar tooth, so in early 2001 it was coming out as well. Abscesses, root canal therapy, bad dentistry and capping had left just a remnant that must be removed, slowly and in very small pieces, so an implant could be inserted in its place.

I am, let me admit it, a total coward around needles and dentists. Many years ago, I found that lying back and doing a complex calculation, like the cube root of seventeen, took my mind off sharp things being introduced to my mouth. There was a problem on this day, however, because after an hour or so, having got my answer to three decimal places, I found I was losing track of the numbers, and while the dentist had lost count of the tooth pieces he was by no means finished. So I cast around for something else to occupy my mind.

I am also, let me admit it, a total slob around research, falling back on the methodology of New Electronic Brutalism whenever possible, using electronic assistants to find what I want. A few weeks earlier, I had been looking into the ways in which we use the word âpie'. I knew Shakespeare called a magpie a Maggot Pie, and while I was relieved to find that Maggot was an old form of Margaret (so Mag Pie was just the sister to Jack Daw), my curiosity had been aroused about pies in general.

I had turned to one of my brutal tools, a monster text file of all of Shakespeare's plays, to search out how the Bard used âpie' at different times. That led me to

The Winter's Tale

, and the plans the Clown lays to make a warden pie, for which he lists his needs:

Let me see: what am I to buy for our sheep-shearing feast? Three pound of sugar, five pound of currants, riceâwhat will this sister of mine do with rice? But my father hath made her mistress of the feast, and she lays it on.

As I lay back in the chair, having my mouth beaten into submission, trying to plan a light essay on the pies of various sorts, the Clown's sugar came back to me. Sugar was the main source of my present dental predicament, but there was something odd about the Clown's list. As I understood it, sugar came to England from the West Indies, and Britain colonised the islands after Shakespeare was dead. So how could there have been any sugar around in Shakespeare's time? Didn't they use honey?

That set me wondering, and that was how this book came to be, because once I was out of the chair I went data-digging, and found that Shakespeare uses the word âsugar' seventeen times in the plays and sonnets to mean sweetness, so his audiences must have understood the term. Still, sugar did not dominate, and âhoney' appears 52 times in his works in a similar role.

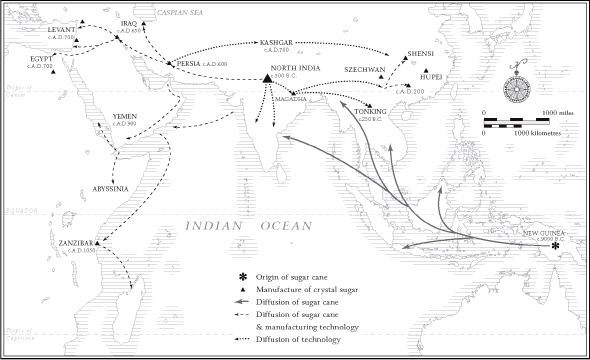

In time I learned that by 1600, sugar from the Mediterranean, from Africa and from islands in the Atlantic was being traded all over Europe. Sugar had travelled a long way from a clearing in New Guinea, through Indonesia, into India, Persia, Egypt and Palestine. On its travels, people had learned how to work with it, even though they had no idea of where it originated, but sugar was by no means yet the maker and breaker of fortunes and empires that it would become.

By Shakespeare's time, people had learned that making sweet tastes is a marvellous way to gather the money that gives power. Ever since, the story of sweetness has been the story of money and power, and the special kinds of corruption that follow from money and power in large amounts. Here follows the story of sugar, what it made, and what was made of it.

ANTI-GONORRHOEAL MIXTURE

Take of copaibe 1/2 oz., spirits of nitric ether 1/2 oz., powdered acacia 1 drm., powered white sugar 1 drm., compound spts. of lavender 2 drms., tinc. of opium 1 drm., distilled water 4 oz.; mix. Dose, a tablespoonful three times a-day. Shake before using.

Daniel Young,

Young's Demonstrative Translation

of Scientific Secrets

, Toronto, 1861

S

ugar cane is a member of the grass family. In botanical language it is

Saccharum officinarum

, a name given to it by Linnaeus himselfâCarl von Linné, the inventor of our modern classification system. This, and five related

Saccharum

species, are placed in the Andropogoneae tribe, along with sorghum and maize. Like other grasses, sugar cane has jointed stems and sheathing leaf bases, with the leaves, shoots and roots all coming from the stem joints.

The world's scriptures have few references to sugar. Sugar rates no mention in the Quran (which, as we will see later, is significant), and while both Isaiah 43:24 and Jeremiah 6:20 refer to âsweet cane', which some people think

might

mean sugar cane, there are a number of other candidates. If we assume that sugar was intended where the Bible's translators wrote of âsweet cane', then the line in Jeremiah, âTo what purpose cometh there to me incense from Sheba, and the sweet cane from a far country?', tells us that sugar cane did not grow around Palestine in Old Testament times. The problem here, as ever, is that we are in the hands of translators who interpreted the Old Testament in terms of their own understandings and assumptions about the past.

The only world religious leader who makes any specific reference to sugar is Gautama Buddha. His words were written down some time after his death, so there may have been some interpolations, but he was probably familiar with at least some form of sugar cane. Buddha was, after all, born about 568 BC, at a time when the sugar cane was probably known and grown in India.

The set of instructions known collectively as the Buddhist rule of life, the

Pratimoksha

, defines

pakittiya

or self-indulgence as seeking delicacies such as ghee, butter, oil, honey, fish, flesh, milk curds or

gur

(a form of sugar) when one is not sick. As this particular rule was laid down by Buddha himself, it suggests he was at least aware of sugar. As well, when Buddha was asked to allow women to enter an order of nuns, he likened women in religion to the disease

manjitthika

(literally, âmadder-colour', after the red dye called madder) which destroys ripe cane fields, and which is caused by

Colletotrichum falcatum.

This fungal disease of cane still exists, going by the common name red rot.

There are other Indian references to sugar from this period, but the exact sort of sugar meant is never clear. Still, it seems there were cane crops large enough to suffer disease in Buddha's time, around 550 BC, and a Persian military expedition in 510 BC certainly saw sugar cane growing in India. The army of Alexander the Great reached India around 325 BC, and Nearchus, one of Alexander's generals, wrote later of how âa reed in India brings forth honey without the help of bees, from which an intoxicating drink is made though the plant bears no fruit'. We now take this to mean that he saw sugar cane and sugar juice, but not sugar itself. This comment has often been used to argue that sugar cane was taken to Egypt by Alexander at about this time, but there is no evidence for that.

The

spread of sugar before it reached the Europeans.

Around 320 BC, a government official in India recorded five distinct kinds of sugar, including three significant names:

guda

,

khanda

(which is the origin of today's âcandy') and

sarkara

. If the date is correct, this would appear to be evidence that sugar was being converted into solids in some way before 300 BC, so perhaps Nearchus did see sugar after all. Remember the

guda

and

sarkara

, because we will meet them again.

By about 200 BC sugar cane was well known in China, although it is possible that it was only chewed as cane. There is a record from AD 286 of the Kingdom of Funan (probably Cambodia) sending sugar cane as a tribute to China. Some 500 years earlier, in the late part of the Chou dynasty, it was recorded that sugar cane was widespread in Indochina. It is also possible that sugar cane was being grown at Beijing around 100 BC, though it is hard to tell how successful this would have been, 40 degrees north of the equator. We do know that sugar cane was already on the move, and could have reached Africa at about this time, and perhaps Oman and Arabia. The important move of sugar (as opposed to sugar cane) onto the world stage seems not to have come until around AD 600, when the cultivation of sugar cane and the art of sugar making was definitely known in Persia, at least to the Nestorian Christians who lived there.

Sugar cane was an important crop in India long before this, and nobody seems to know quite why it took so long to reach Persia (modern Iran). Perhaps it has to do with the irrigation that the cane needs in dry areas. In AD 262, Shapur I, a Sassanid king, made a dam at Tuster on the Karun (Little Tigris) River in Persia to irrigate surrounding areas by gravity feed relying on the height of the waters behind the dam. The water was eventually used to irrigate cane, and the ruins of the irrigation works are still there.

The centralised system of authority that was the Persian empire would have allowed the development of large-scale irrigation schemes. Major irrigation schemes anywhere, like the terraced rice fields of Java and Bali, the fields along the Nile and Australia's irrigation areas, all rely on a central authority to provide organisation and an imposed peace.

A community of Nestorian Christians was certainly making good sugar in Persia around AD 600. If the art of sugar making had now been perfected, this could explain why sugar suddenly took off. The crop and its product had only spread slowly up until then, so clearly something happened: either there was a change in the method of growing cane or in the methods of extracting sugar, or maybe there was a change in the nature of the cane. Then again, as many writers have suggested in the past, perhaps sugar just followed the spread of Islam, once Islamic forces had defeated the Sassanid dynasty of Persia.

THE TRUE INVENTORS OF SUGAR?

All over the world, the word for sugar seems to come from the Sanskrit

shakkara

, which means âgranular material'. We find words like the Arabic

sakkar

, the Turkish

sheker

, the Italian

zucchero

, the Spanish

azúcar

, the French

sucre

and, of course, the English âsugar'. It is

sukker

in Danish and Norwegian,

sykur

in Icelandic,

socker

in Swedish,

suiker

in Dutch and

zucker

in German. Yoruba speakers in Nigeria call it

suga

, Swahili East Africa calls it

sukari

, Russians call it

sachar

, Romanians say

zahar

and the Welsh call it

siwgwr

âand when you allow for the Welsh pronunciation of âw' (rather like âoo' in âbook'), the pattern is retained.

Bahasa Indonesia is one of the few languages where this pattern does not apply. Here, the name for sugar is

gula

, although when biochemists in Indonesia speak of âsugars' as a group the name they give them is

sakar

. The Arabic origins of that are clear enough, but that expert among experts on Malay etymology, R. O. Winstedt, said in his early twentieth-century dictionary of the Malay language that he could see the Sanskrit origins of

gula

just as easily. But he said so without knowing that sugar cane originated on the island of New Guinea, at the far end of the Indonesian archipelago. Tradition then had it that sugar cane originated in India or China, and Winstedt was an old man when its true origins were worked out.

Few Europeans know much of the immense Hindu influence on Java and Bali. The various Javanese empires traded with India over many centuries, and perhaps sugar in a prepared form was first traded to India from Java, not the other way around. In that case, when the art of sugar making was learned in India, a Sanskrit word similar to the established Indonesian word would have been applied to the product the Javanese knew as

gula

. So

gula

would have given its name to the Indian

gur

, rather than the other way around.

Why would the Indians call it

gur

? The European linguists say the sugar came out of the boiling-pan as a sticky, treacly ball, and

gur

is a Sanskrit word for a ball. All the other lands heard about sugar as

shakkara

. Why would Indonesia alone have a different name for sugar, unless it was their word to begin with?