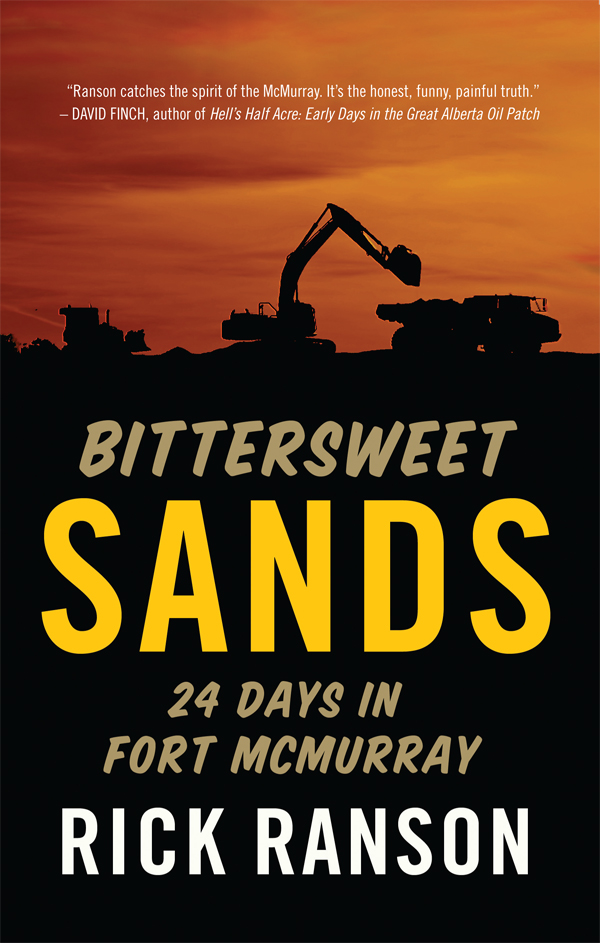

Bittersweet Sands

BITTERSWEET SANDS

Twenty-Four Days in Fort McMurray

Rick Ranson

Copyright © Rick Ranson 2014

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication â reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system â without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying of the material, a licence must be obtained from Access Copyright before proceeding.

Bittersweet Sands is available as an ebook: 978-1-927063-63-7

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Ranson, Rick, 1949-, author

Bittersweet Sands: Twenty Four Days in Fort McMurray / Rick Ranson.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-927063-62-0 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-927063-63-7 (epub).--

ISBN 978-1-927063-64-4 (mobi)

1. Ranson, Rick, 1949- --Anecdotes. 2. Fort McMurray (Alta.)-- Anecdotes. I. Title.

FC3699.F675R35 2014 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 971.23'2 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C2014-901853-3

C2014-901854-1

Editor for the Board: Don Kerr

Cover and Interior Design: David A. Gee

Author Photo: Fred Elcheshen, Elcheshen's Photography Studios

First Edition: October 2014

NeWest Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Alberta Multimedia Development Fund, and the Edmonton Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

| 201, 8540â109 Street Edmonton, Alberta T6G 1E6 780.432.9427 www.newestpress.com |

No bison were harmed in the making of this book.

We are committed to protecting the environment and to the responsible use of natural resources. This book was printed on FSC-certified paper.

Printed and bound in Canada

To Isabel Ranson.

We miss you Mom.

Every damned day.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Day Two â

Selling Time in Ft. McMurray, Set Up

Day Three â

Starting Over, First Email from Doug

Day Six â

Big Mistake, Email Day Six

Day Nine â

Oxygen Content, Emeralds and Snakes

Day Ten â

Lobotomy's Phone In, That Loud Man

Day Eleven â

C6, Email Day Eleven

Day Thirteen â

Redoing the Job Hazard Card

Day Fourteen â

Frozen Hams, Email Day Fourteen

Day Fifteen â

Jason by the Radio, Double Scotch's Issues

Day Sixteen â

Lobotomy's Final Phone In

Day Seventeen â

Lunch Break, Email Day Seventeen

Day Eighteen â

Gas Monitor, a Lesson in Love

Day Nineteen â

You Can't Drink Him Pretty

Day Twenty â

Stretches, Terminated

Day Twenty One â

Too Tall Won't Be With Us Anymore

Day Twenty Two â

“Got Ten Bucks?”

Day Twenty Four â

The

Great Eastern

, Lonesome Road

“A bunch of welders went to McMurray for pre-shutdown. They've cleared fifty thousand already. It's going to be a big one.”

The voice on the phone didn't wait for, or want, an answer.

“I'll bet they got closer to sixty thousand, maybe even a hundred. Well fuck a wild man, a hundred thouâ”

The voice on the phone had to get off. He had to tell more people. As if the telling made him part of the riches already.

I was going to Fort McMurray. From every part of North America: from farms, cities, and small towns with names like Portage La Prairie, Indian Head, Red Deer, and the aptly named Hope, from across the continent, men and women answer that call. They pack bags, fuel cars, kiss their sweethearts with a speed verging on frantic. In their bags they throw enough underwear and socks for a week, shirts for a week, blue jeans? Blue jeans are forever. Everything depends on the workersâtheir wants, their needs, their safety. Controlling workers is like herding cats. They have to be housed, fed, paid, protected, cajoled, nursed, ordered, and, if need be, fired. Materials can be ordered months, even years in advance; workers can't. Steel can be stored in the snow; men can't. Equipment prices can be discounted if bought in bulk. Men? No, manpower is the great unknown.

These are hard, obscene men who bark when they laugh, because that's what gangs do. Men who are used to working with their bodies, who are not shocked by the sight of their own blood and the blood of others. Men who are accustomed to staying in cheap hotels or construction camps, moving from refinery to refinery, province to province, country to country. Men who drive back and forth down that Trans-Canada Highway, following the work like the Inuit follow caribou.

Before that first worker in a refinery pulls a wrench, shuts a valve, or clicks a computer's mouse to stop the oil flowing, engineers have been planning that twenty-four-day refinery makeover for years.

A scheduled work stoppage is a finely tuned choreography of obtaining materials, leasing cranes and equipment, hiring workers. While the Fort McMurray refinery plans their shutdown, the engineers take into account that they are in competition with all the other shutdowns all over North America, and there's a finite number of supplies and manpower on the continent. What looks to the unschooled eye like rats on a carcass has in fact been planned years in advance. Engineers have made fortunes just developing the computer programs that schedule shutdowns down to the minute.

Orders are sent out to construction companies and unions to supply boilermakers for the pressure vessels, pipefitters for the hundreds of miles of pipes, electricians, scaffolders, carpenters, labourers. And welders, welders for everything.

Planning engineers generate the Work List and the resulting Materials List. The Turnaround Team sends out work packages so that when a man shows up in Fort McMurray, he is assured of a bed and food. Everything comes together in an interweaving of men, materials, tools, camp space, food, and time.

Finally that one day comes when the Turnaround Manager looks around a room at other engineers and all the Turnaround Team members from every section of the refinery. He looks at his watch and orders the closing of a valve, the locking out of a switch, or the turning off of a bank of motors.

The shutdown begins.

The black gold dribbles to a stop, the lights in a thousand sensors dim, the needles in hundreds of gauges freeze. The refinery lies still. All that piping and all those vessels seem to sag, then slip into a lassitude of waiting. The thunderous, vibrating rumble of a working refinery becomes just a memory of an echo. The only sound within the now-sinister labyrinth of pipes and chrome is the faint but constant hiss of heating pipes like a steam locomotive idling in a railway station. Small wisps of escaping steam smell of wet cement, oil, and the rotten-egg whiff of hydrogen sulfide. Men speak in whispers at such times. They look over their shoulders as their steel-toed boots clang in the quiet, echoing on the steel grating. The pipes that once vibrated with the precious liquid now hang limp, glinting dull in the sun like a burnt-out forest of tar-streaked chrome, all right angles and silence.

Before he had clicked off, the voice on the phone had a final excited message:

“After the first shutter, they're going to transfer everybody to the second one, then a third, and on and on. Jeez, man! A thousand guys, seven twelves, maybe fourteens. We'll be buying our own Brink's truck to carry the money. I'm getting on that shutdown. This'll be the biggest shutdown this year.”

My truck roared to life. I was hustling out west.

Going to McMurray.

Going to a shutdown.

I was enveloped by a thing alive. A hundred blue-jeaned men, jostling, clumping, or slouching against white cinder block walls like discarded garden tools in a basement. The throng in the middle of the floor moved and twitched like cattle infested with ticks. The hall shimmered with the electricity of men who were drawn to the protection of the mob, but who at the same time wouldn't hesitate to elbow their neighbour aside for a chance at McMurray's riches.

Men eyed men appraisingly.

I nodded to several men, glanced at a few more, and shot a dark look at a chinless man. The man returned the challenge.

The crowd stood in ragged semicircles facing the dispatcher's desk. To a man, they jammed their hands deep into their pockets, or crossed their arms, hunching, hiding their hands. Always hiding their hands. I pulled my hands out of my pockets, played with them for a while, then shrugged and put them back.

Low murmurs were interspersed with laughter.

“One thing about Daks, you really don't have to ask him what's on his mind.” The speaker's heehaw laughter sounded like a dull saw slicing green wood.

I nodded towards the speaker. The young man smiled, his eyes sweeping the room to see if anyone else noticed.

A metallic bong from the microphone echoed through the hall, indicating the dispatcher was ready. Every face turned towards the desk.

His voice surrounded the men.

“Jimco Exchanger, Firebag, night shift, five mechanics, ten B Pressure welders, six-tens, two weeks plus, drug and alcohol test.”