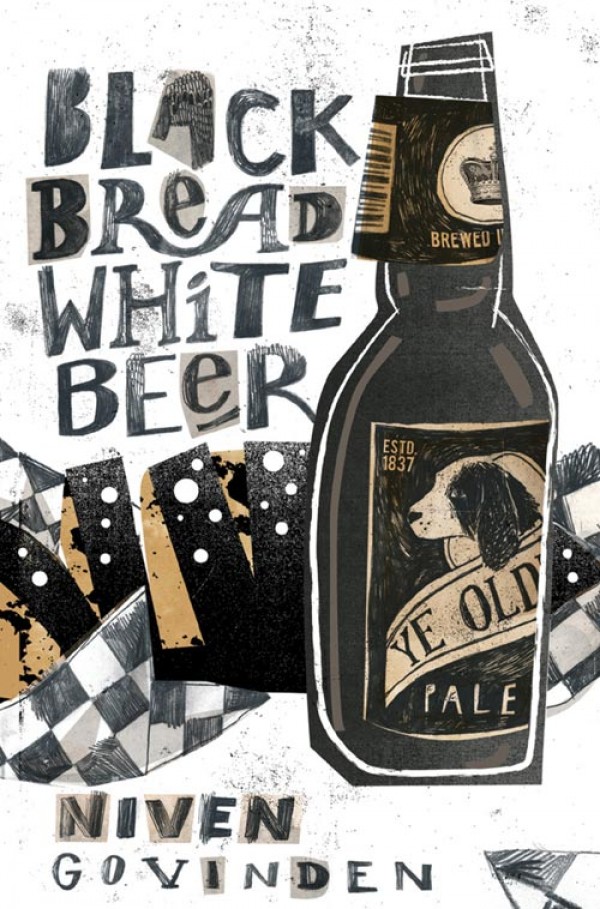

Black Bread White Beer

BLACK BREAD

WHITE BEER

Niven Govinden

FOURTH ESTATE â¢

New Delhi

T

he two men squat tentatively in their dinghy, floating without enjoyment. There was trouble casting off in the meagre dawn light, one man slipping on shit-splattered cobbles and getting his foot in the water earlier than anticipated. His leg twisting up and out at a sharp angle as he struggled for balance, as if teaching his colleague a new dance move. He is still swearing now, like a teenager, loudly, no restraint; deities and mothers are named in vain. There is no one around to take offence because it is too early for anyone to be out in the park. No one, that is, except a sleepless Amal, sitting on a bench partly hidden by trees.

He watches their nervousness morph into confidence a few metres out, as they paddle with gloved hands towards their destination, the birdhouse in the centre of the lake. Their movements are losing their jerkiness and are becoming smooth and in tandem, a challenge to those Oxford and Cambridge boys who firmly believe that

rowing is not a trick that can be learned in five minutes on a glorified duck pond. The man with the dry feet tells a joke that makes the other laugh dirtily. Council-issued fluorescent body-warmers shake with mirth.

But there is still enough grace to put paid to that. The water, algae-ridden but forgiving, absolves their earlier coarseness. Within a couple of minutes they are silent, allowing these unfamiliar sounds to form their new language: the swoosh of the craft, and the drip of their hands, as they plunge in and out. Amal, who cheers-on the boat race most years from a beer tent near Putney Bridge, whose armchair love of sailing extends to an occasional bit-part within the tourist gaggle which breathlessly applauds the arrival of yachts in European marinas, remains silent, unwilling to intrude. The three of them, absorbed with blending the peacefulness of morning to their differing agendas.

At the birdhouse, a bulky, unstable plywood construction turning black with rot, the men throw over a thick sheet of netting. Neither wishes to risk unsteadying the dinghy by getting to their feet, so the throw itself is generated from a position on their knees; one that is weakly weighted and only just lands on its target. Not cut to size, it snags on the pointed roof, and falls over the squat, low doorway. The bottom, knotted in places, frayed in others, trails into the water. There is no checking to see whether there are any visitors inside. There are feathers around the

decking, and fast collecting in the net, but this means little to them. They are not Wildlife Protection, but Parks Maintenance, there to do the job asked of them, and no more. They look forward to coffee and bacon rolls in the van and a tick on the list that means they are closer to home.

The netting is of a very dark green, that will appear as black as the birdhouse itself once it weathers, rendering it almost invisible from a distance, from the air. It is also taut, and of a density that a beak would find impenetrable. If there is any concern that a duckling may still be inside, the men do not show it. There is no pause in either paddle movement or direction as they return to bank side, where the van is parked. Only in the final metres does the posture of the dry man shift. His head cranes as far sideways as the balance of the dinghy will allow, the furrow in his brow suggesting a rush job, something overlooked.

Amal, too, listens for a further layer of sound, over the whoosh and plunge â a crackle, a cry, to confirm all that he suspects. Long after the council van has gone, as he shakes his empty cigarette packet and heads for the park gate, he hears it: the tinny, metallic squall of a youngster, and a rustle of the net. He has the urge to look back, to possibly wade in, and attempt rescue, if rescue is needed, but buries it. Ducks are meat, when it comes down to it. No looking back. He walks away, towards the car, crunching

the fag packet in his hand, his teeth repeatedly grazing his lower lip. He is learning that not every life can be saved.

He should clean the car. Have it cleaned. It must be spotless when he goes to collect her. Most of all, it must smell fresh. Already he is planning on leaving some flowers on the back seat to mask both the dry artificial scent of a new car and their own additions over the past day. Seat leather and metal mixed with her perfume was a heady combination that made the drive to work that much more pleasurable. He could sit through two hours of bumper-to-bumper traffic on the M25 with a smile on his face just breathing it in. But this new blend, with the additions of rapid, thick perspiration, and a few drops of urine, and blood, bond too heavily with the intoxicating top notes. With every breath he smells both of them; their fear distilled.

Next to the station is a twenty-four-hour multi-storey car park where two Polish guys offer a valet service from the basement. He has used it a couple of times on commuting days, when he was too late finding a parking space on one of the residential roads. Spotless work, but overpriced. But the car needs it. He feels the urgency of this one task, the stranglehold it seems to have on his guts. He must complete this one productive thing before he meets her.

He is surprised about the looseness of his wallet, how he has been spending so freely since it happened. Thirty pounds on dinner at a gimmicky steakhouse restaurant because he did not want to eat at home alone; twenty pounds at the petrol station off licence; ten pounds at Starbucks which included the purchase of a big band CD which now sits in the glove box, unopened, and finally the twenty-odd he would be charged at the valet place. Claud would tease him in perpetuity if she ever got wind of the spree, emptying out his pockets and looking for moths. Where are they, she would ask. What has happened to my tightwad husband? Is it your birthday? A leap year? She would have, then. Now, who knows?

The Pole is already hard at work waxing an Audi bonnet crisscrossed with blade scratches. Amal is relieved to see that he is the same guy from before, wiry and in his mid-thirties, attentive and eager to please.

âIs no problem. Soon as I finish the Audi.'

As with all men of a certain age there is a brief, flickering appraisal of the state of each other's bodies and hairline.

âAny chance I can cut in? I'll pay more if it'll help.'

âI don't know, sir. I like to finish one car at a time. If I don't use up the wax while it's wet, I have to start the whole thing again.'

âPlease. I have to be somewhere . . . and it's important that the car looks nice. Please.'

The last time he detected a pleading note in his tone was yesterday, something he does not like to remember. Both the timbre and the weakness it implies are detestable. It is a slippery slope. He can see that unchecked, how easy it would be lapse into the same sentiment in everyday situations, from cajoling an officious parking attendant, to queue jumping at the post office. Better to dirty himself with money, folding two twenties and pressing them into the waiting palm of the flexible Pole, only to find his bribery is unwanted.

âYou have given me too much. Full valet is twenty. Here, go have coffee with the extra money.'

His thanks are conveyed through stutter, another bridge to yesterday, when he struggled to communicate with doctors and the nursing staff. He is also conscious of the Pole finding him a halfwit, and loathes that also. The brain is capable of remembering too much; there are too many links. He wants every action and impulse to differ from his behaviour yesterday. He needs everything to be normal, for both of them.

At the coffee shop he waits, second in line, before ordering double espresso and biscotti, as if he hadn't taken enough comfort in carbs last night. The caffeine jumps starts him, frighteningly fast, making a mockery of his sluggish constitution. Whilst there are no free tables, there are seats dotted around the floor and along the side bar, but he is conscious of sharing the cramped space with

strangers, fearful of the need he has to talk. Once he starts he will not be able to stop. No one has been told about Claud, and this is not the place to start.

He takes the biscotti and another espresso back for the Pole.

âOK if I sit in the car? I'm a sad case with nowhere to go.'

There are places, across the road and closer to Richmond Green, but he is known; the price of three married years of melding into the community. The idea of bumping into someone, having to fall into pretence, to sign whatever petition is being championed that week, to care, almost makes him shit in his pants. All he wants to do is hide.

The Pole sees the humour of his situation. Makes a series of rubbing movements with a damp cloth across the windscreen.

âLike you're in the big machine carwash? Sure. I'm finished, anyhow.'

He has been gone twenty minutes and bar the wheels, the car is almost dry. He holds out the paper bag, shakes it towards the Pole with some urgency because he realizes he now longer wants to hold it, wants to be out of there.

âYou drink espresso, right?'

âWhere I come from, mothers raise children on hot milk. Tea sometimes, but mostly milk. Coffee is more of a luxury. I know people back home, the older people, who still keep jars of Nescafe hidden under their beds! It's

still that valuable to them. Our vodka runs like water, but coffee is hidden. Is it the same in your country?'

âMy parents come from a tea-growing part of the world. I wasn't allowed to drink anything else.'

âHa! Thank you, my friend. This is appreciated. You were here before, I think? With the yellow Mini Cooper.'

âMy wife's car.'

âWife, good. Mini is a fine car for a woman, but a man needs something . . .'

His lips broom-broom over the open espresso as he cools it. The noisemaking is as loaded as the coffee, macho-aggressive, but casually so, as basic a part of his constitution as the protons and neurons of his make-up. He imagines how easily this must be deployed in other situations, when chatting up a girl, and later, in bed, something only a man who still finds such posturing difficult to summon would recognize.

âThis BMW is a better car. It will impress people when you drive to your important meeting. They will say that this is the car of a successful man. And when they notice how clean it is, they will be even more impressed.'

âI'm not working today. I have to collect my wife from the hospital.'

âShe is sick?'

âWe had a miscarriage. Yesterday.'

âI am sorry to hear that, brother.'

âEverything's fine, well, she's fine, now. They kept her

in only because there was a spare bed. Monitoring her, you know. Procedure. It's just been a shock.'

âIn my country, this is something we do not speak of. It is kept in the preserve of the women.'

âMy country too.'

Automatically, he bows to the Indian gene. Though he thinks of himself as educated and enlightened, it is always the pull of the genes that navigates him through crisis, as if there was a state of sense-making that comes solely from the combined force of his parental cells. Before yesterday, he did not think to analyse such superstition. Now, maybe, is the time for its reappraisal.