Black Fire (14 page)

Authors: Robert Graysmith

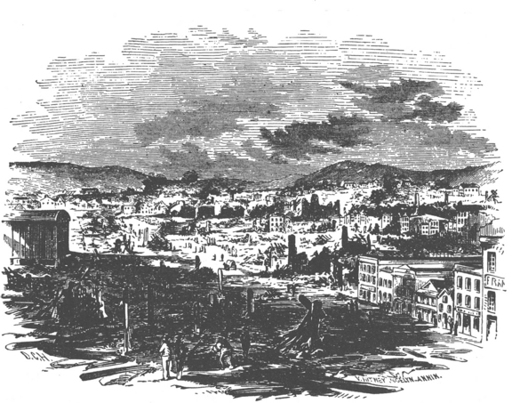

The next day there were still frequent explosions of powder, dull rumbles like an earthquake below ground. Dunbar’s Bank, rebuilt after the Christmas Eve fire, tacked up a notice on its outside wall: “Open as usual.” The bank, a simple brick safe with fire ventilations, was just large enough to admit three standing customers at a time. Remarkably, it stood alone at the center of a hundred yards of flattened ruins. J. J. Bryant, who had been defeated at the polls by Coffee Jack Hays in the race for sheriff, had better fortune this time. After the fire was beaten, his hotel and gambling den, 150 feet above Kearny Street, was the only house still standing in the entire city. Broderick got to the scene in time to see flames still flickering on one block while lumber was being hauled for a new house on another block. By evening, two new frame buildings covered with canvas had been completed by the light of dying flames. Fifty similar structures flew up. “Claptraps and

paper houses,” Broderick said in disgust. He doubted anyone would be erecting expensive wood buildings soon. No one would insure them. Yet money was everywhere in the boomtown. Broderick had only to kick at the ashes to see a large quantity of melted gold glittering like a bright river under the charred ground. Try as he might, he could not find one long face among the crowds. Every man looked as if he would momentarily have more money or take on another blaze without a qualm. “What spirit!” he thought and let all the air leave his body at once. He coughed and steadied himself. The old Central American illness had attacked his fragile lungs again.

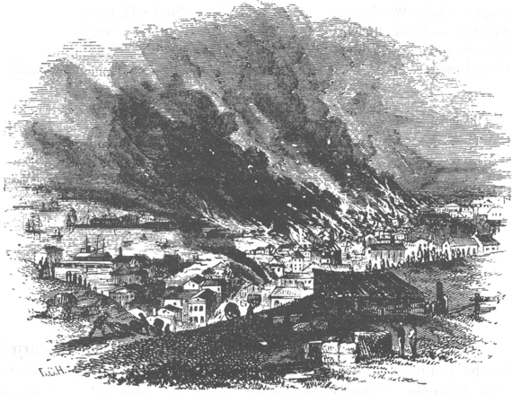

That night the Town Council convened in the ruins to tabulate the damage. Three-quarters of a mile of San Francisco had burned, sixteen blocks including ten blocks bounded by Pine, Jackson, Kearny, and Sansome streets and five more bounded by Sansome, Battery, Sacramento, and Broadway. The city lost three hundred buildings and fifteen hundred single dwellings, losses totaling around $4 million. Though the conflagration had started on the same ground as the Christmas Eve fire, it had burned three times as much area. “All but a few buildings out of three blocks were destroyed,” a Council member commented, “and these blocks are the very heart of the city. The loss has been very much greater than can be estimated with any degree of certainty. We shall not recover from it for some time.” He sat down hard in the ashes. A cloud of soot covered him. “It’s folly to keep rebuilding the same blocks over and over,” he moaned, but nobody listened. The townsfolk were busily rebuilding on the smoking earth of the burned-out area. Within ten days the industrious citizens had rebuilt more than half of the incinerated area—just as flammable as before and stretching along impassable, “jackassable” roads that made getting to fires impossible for the volunteers.

The Council ordered the digging of artesian wells with a capacity of three hundred thousand gallons. Portsmouth Square had been the flash point of both big fires, so they designated that a twelve-thousand-gallon cistern, a square wooden box of tar-soaked planks with caulked seams and flat wood covers, be installed there. Fifteen more were prepared, each holding nearly fifteen thousand gallons and sunk ten to fifteen feet underground. Next, the Council set heavy fines for noncompliance with the city’s first building ordinances banning cotton-cloth buildings outright, ordered each homeowner to keep six leather buckets of water always available, and made it a crime not to render assistance

during a fire. Any person who refused to fight fire or assist in moving goods to safety would be fined $100. Next, they ordered men into the dead flotilla of deserted ships to find, as Sawyer had, buckets, lengths of hose, and planking. All this belated activity only enraged the friends of the late Captain Vincente, who stormed City Hall along with those demanding compensation for fighting the fire. When the Council refused them all, a near riot broke out.

The following day, the mayor offered a $5,000 reward for the incendiary’s capture. The coordinates of the fire had now left everyone convinced that the blazes were the work of an arsonist. Within a year a claim would be made by a condemned Australian prisoner that the Lightkeeper was an Australian brigand named Billy Shears. No one could offer a motive for Shears to have set the fires and he had left the area before more fires were set. Only merchants had benefited by the fire. Sawyer turned his scrutiny on them. Before the blaze they had enough surplus lumber to rebuild the city thirty times. Afterward lumber prices quadrupled. Rich merchants like Brannan enhanced their social standing by contributing equipment, real estate, and funding to a specific engine company. William Howard, a prosperous merchant, had personally cosponsored Company Three, comprised entirely of Bostonians. A commanding figure—six feet tall with full ruddy cheeks; sparkling eyes; and a soft, musical voice—his most recognizable mannerism had been the habitual stroking of his full sandy beard in thought. Now he was clean-shaven. Unquestionably, he was the town’s first citizen. He had arrived as a cabin boy on the sailing ship

California

and immediately had become a collection agent in charge of hides and tallow and then formed the most active commercial firm in town with his partner, Henry Mellus, to buy the Hudson’s Bay Company’s property.

Company Three, having failed at being Company Number One by a few hours’ delay in filing, was still fighting over its name. One faction wanted it to be called the Howard in honor of their benefactor’s generosity. The other remained loyal to the company’s other angel, Sam Brannan. For a while both rivals sabotaged each other. The drawn-out battle ended only when the Brannan faction stole the company fire engine during the night and ran it into the bay. In the days it took for the Howard faction to extract the pumper and the week it took to restore its unsullied condition, both sides reached a truce. But the title that found favor with the public was not the Howard, the Brannan, or the more formal Eureka. A fire and an explosion inspired Three’s final name. Their

first engine house, an old warehouse belonging to the Stanford brothers at Pacific and Front streets, stood so close to the water that one day half of it plunged into the bay. Company Three stored their gunpowder in the remaining half. When five thousand cases of coal oil in the basement ignited, the oil curled in a burning stream along Battery Street. Flames ran back along the same stream and detonated their stored explosives. As a replacement, Howard built a lavish and elegant brick-and-stone-fronted building on Merchant Street between Montgomery and Sansome streets. The upper story became a lavishly furnished meeting room. In their new posh surroundings Three became more convivial, ostentatious, and social than Broderick One and Manhattan Two combined. They threw glittering balls for the two thousand women who had arrived in town in January and February. On gala nights they moved their fire apparatus into the street to allow room for dancing. As the most congenial volunteer unit, folks dubbed them Social Three. They had the city’s finest singers in their glee club and their piano pumped music at all hours. Three’s men were dressed in full regimentals when raven-haired Lola Montez debuted the “Spider Dance” at a benefit. Sam Brannan, having forgotten he was married both in San Francisco and Utah, was smitten with the fiery dancer, but had quarreled with her and refused to attend. Social Three filled their leather helmets with flowers, showered the stage with them, and elected Lola as an honorary member. After her performance they carried her home on their shoulders. When they gave a banquet at the American Exchange, their bill of fare alone, printed on the richest of dark blue silk in pure gold ink, cost $5,000. They drank more champagne than all the water they ever poured on a fire and, impatient to drink, did not wait to draw the corks, but knocked the tops off with their axes and drank while they beat out flames with wet sacks and brooms. With 537 local drinking houses to choose from, the jolly comrades overindulged at every opportunity.

Three months earlier, when the Council had enlarged the San Francisco police force to fifty men, Brannan had reported a deficiency of funds in the city coffers and cut the force back to thirty members. It was then that the Council decided to inexpensively thank the new fire departments by channeling their recent animosity toward one another into peaceful public displays and decided to launch the annual Volunteer Fireman’s Day to show their gratitude to the men who had saved San Francisco. It would also give Broderick One, Manhattan Two, and Social something to occupy their time. The valiant volunteer companies could

compete in a parade and calm their nerves while waiting for the city to burn again. Broderick agreed. He had earlier laid out a plan to confine competition among the three firehouses to the parade ground.

A recent Chicago parade had featured nine hundred firefighters carrying ornamental axes and elaborately engraved silver speaking trumpets while riding on stunning parade vehicles. When any firefighter died, his fellows deployed the company hose cart as a hearse and the entire city turned out to share their grief. The volunteers were not only heroes, but family members and an extension of the citizens themselves. The fledgling San Francisco companies kept two sets of uniforms—one for firefighting and a more ostentatious costume for ceremonial purposes. The volunteers pressed their dazzling full-dress uniforms and assembled a dazzling array of parade coats, belts, ties, suspenders, capes, gauntlets, shields, and decorative fire hats of felt and leather for the day. Coach and sign painters painted fire company names and heroic oil pictures on helmets and fire buckets. They depicted countless eagles, flags, and burning buildings on the sides and end panels of massive water wagons, a rolling, functional canvas for a magnificent parade. On parade day, the two-fisted fashion plates strode from their engine houses. “The chief interest … of the exhibition lay in the appearance of the men themselves,” the

Annals

reported. “They were of every class in the community and were a fine athletic set of fellows.” San Francisco might be the City of Gold, but silver dominated the volunteers’ parade. The men wore silver watches, jewelry, and capes; and their chiefs blew silver trumpets, all except Brannan’s personal company, Social Three. His volunteers, who cut dynamic figures in their formfitting black trousers and patent leather helmets, wore expensive gold jewelry and cloth-of-gold capes to their fires. Foreman Frank Whitney had a gold speaking trumpet, a priceless instrument he liked so much he megaphoned orders to men standing right next to him. “Their foreman was a figure of such worshipful splendor—an uncommon human being, that you would have thought he could have put out the world if it were burning,” commented William Dean Howells, the realist author and critic.

Swaggering and full of confidence, the volunteer companies in blue leggings, leather hats, silver- and gold-trimmed capes and gleaming boots presented a heroic sight, their freshly trimmed beards set off by high collars and elaborately decorated vests. The chiefs were known by their white helmets with gold lettering and long white coats with enormous

side pockets to hold their trumpets. In every way their getups outshone the militia in the same parade. With luminous silver ropes, the firemen drew three gleaming engines through the muddy streets. Supporters decked them with ribbons and wreaths, and draped the fire engines with banners and bouquets while brass bands played firemen’s quadrilles and polkas.

As the opposing fire companies filed past one another, it was their practice to shout out slogans. Kohler, aware of the tense situation growing between rival units, ordered his men to keep a civil tongue. “No insult should be allowed to interrupt the good feeling and harmony among the three companies,” he said. That would change soon enough, but during that first parade, amid the throng cheering from the ruins, goodwill ruled. Now at the sound of any alarm, all Boomtown poured from their combustible houses to cheer on their favorite volunteers as they would a favored sports team. San Francisco had swiftly taken the new volunteers to its heart. “Almost without exception the firemen here are gentlemen and almost every gentleman in town is a fireman,” a local man wrote home. “I never saw any men work as well and as hard as they do at a fire, fearing nothing but failing to stop destruction.” Each night that the torch boys ran, carrying torches high, scanning the roads for debris, detours, and obstacles, they never ran alone. When on calls, they heard, mixed with the labored breath of the firemen pulling the heavy engine, the panting of other boys who thrived on the excitement. Behind them, drawn by panic and calamity, the populace, in bedclothes, followed the engines en masse as if they were sleeprunners—wide-eyed, features fixed, and faces white as paper.

FIRE OF MAY 4, 1850