Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (23 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Yet for a fraction of New York’s black community, the late 1840s and 1850s were years of phenomenal success. Self-consciously identifying as an aristocracy, determined to find an economic niche for themselves despite the city’s rigorous competitiveness, and eager to prove to the world that they too could achieve, this new generation of the black elite thrived. Peter Guignon was still struggling, but Philip was rapidly coming into his own.

The 1840s proved to be difficult years for Peter. Rebecca died after a few short years of marriage. I haven’t been able to find out anything about her death. It haunts me. When and how did my great-great-grandmother die? Where is she buried? Why didn’t Williamson say more about her in his genealogy? Why did Maritcha never mention her?

Sometime around 1847, Peter married Cornelia Ray. Their wedding date had to be after Elizabeth’s birth in 1842 but before that of their son Peter in 1849. By marrying into the prominent Ray family, Peter made an even greater leap up the social ladder than he had with the Marshalls. But although this marriage gave him status, it didn’t bring economic stability. While his former classmates pursued a higher education and became doctors, teachers, ministers, and small businessmen, it’s difficult to figure out exactly what Peter was doing.

Peter is listed in the city directory for the first time in 1845 as a porter, and then in 1846–47 as being in “segars.” Why cigars? I have two tentative explanations. James Guignon is listed in the city directories as a tobacconist on Chatham Street from 1804 until the 1820s. If he was indeed Peter’s father, it’s possible that someone in the family still had contacts in the tobacco business and decided to help Peter out. Maybe that contact was a Lorillard, since Peter Lorillard’s first shop was located close by on Chatham Street. Or maybe it was Peter’s new father-in-law, Peter Ray.

Peter Ray was one of the black community’s most respected members. He had been active at St. Philip’s since its inception, serving as the vestry’s senior warden for all but two years between 1843 and 1862. He worked tirelessly on behalf of black education, cajoling the public school system into hiring black teachers. Above all, Ray had steady employment and a steady income. He spent his entire life working in Peter and George Lorillard’s tobacco company, beginning as an errand boy in 1811 and ending as a general superintendent in the company’s new factory in Jersey City until his death in 1882. Ray profited from white patronage in a relationship that was as equitable as he could have hoped for, undoubtedly because he brought a special skill to his employers, which they recognized and rewarded accordingly.

2

Sometimes it pays to be distracted while doing research. After reading about Ray’s connection with the Lorillards in his obituary, I went to the Arents Collection at the New York Public Library to find out more about New York’s tobacco industry. There I found a small notebook written for the Lorillards, titled “Receipts, chiefly for curing tobacco and preparing snuff,” and began poring through its many handwritten receipts. When I got to blank pages midway through the notebook, I assumed there was nothing else in it. Returning the notebook, I mistakenly picked it up upside down, and it fell open to a new front page. It read in its entirety:

Peter Wray or Ray

Is the name of the mulatto man who sorts out the tobacco for Lorillard, and who is so great a judge of Leaf Tobacco, and which will do best for snuff and which for cutting

for smoking and chewing tobacco. To find him look in the New York Directory or ask one of Lorillards men. 27 december 1842, he was working for Lorillard in his factory in Laurens St. New York.

3

I can only call this a case of dumb luck. The note confirmed my suspicion that Ray was indeed indispensable to the Lorillards’ business.

Peter and George Lorillard got their leaf tobacco from the South, mostly from Virginia and Kentucky. Once picked, stemmed, and cured, tobacco leaves were pressed into hogsheads measuring approximately thirty-eight by fifty-four inches. They were then either rolled down the road hitched to a wagon or swung onto ships to be transported to tobacco manufacturing centers. The principal destinations were southern states—Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, Missouri—but also New York City. Once unloaded, the hogsheads were taken to a warehouse for auction. Complaining of insufficient space to conduct public sales of tobacco, George Lorillard and other dealers petitioned the Common Council in 1824 to allow auctions at the foot of Fly Market Street, close to the spot that had once been New Amsterdam’s principal slave market.

4

It was said that the Lorillards bought their tobacco in person. But if Peter Ray was such a great judge of leaf tobacco, I’m sure they took him with them. They would begin by opening the hogsheads. Ray would carefully inspect the leaves for quality, and decide which to buy. He had to select with great care, for the Lorillards put their tobacco to many different uses, either reselling the leaves in their Chatham Street store or manufacturing various products in their factory. The Lorillards followed fashion, making whatever pleased their customers. Initially, they manufactured tobacco for pipe smoking, but by the early decades of the nineteenth century they were producing snuff. By the 1840s, they had turned to cigars as well as chewing tobacco. And of course much later there were cigarettes.

The Lorillard company was renowned for its snuff. Taking snuff had come from France and Britain to the United States, where it was first fashionable among the upper classes before filtering down to com-Peter

moners. Both men and women used it. The snuff user placed a small amount of tobacco between forefinger and thumb, held it against one nostril and then the other, inhaled, and then expelled the tobacco into a handkerchief. The goal was to provoke a sneeze that simulated sexual pleasure.

5

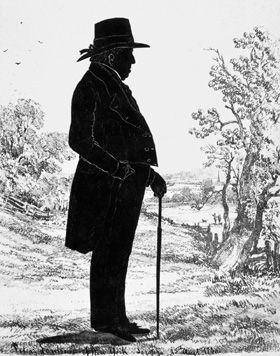

A. Lorillard, lithograph by Auguste Edouart, 1840 (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Robert L. McNeil, Jr.)

The Lorillards had a secret recipe for making Maccoby Snuff, and many believed that Ray was in on the secret. I found the recipe spelled out in great detail in the Lorillard notebook, so I’ll share it with you. Condensing its sixty-odd pages, it goes something like this:

Buy a mixture of tobacco leaf from Kentucky and Virginia, preferably around two years old, and make sure it’s not too ripe but is as sweet as possible. Cut off the butts, or heads,

and pile the leaves in a dry place for three to four months. Then put the leaves in bins for casing or curing, wetting it with liquor (rum, gin, or brandy) and salt water. To make the dry composition, add one tablespoonful refined gum camphor (“get best kind”), coarse salt (“roast it a good deal like coffee”), one tablespoonful gum Arabic (“you had better get the best gum and pound it yourself”), one tablespoon Gum Guiac (“avoid the black, tarry flavored kind, pay the druggist a little extra”). Be sure not to omit any ingredients: camphor gives life and power, and burnt salt flavor, while gum Arabic imparts a sweet taste and Gum Guiac sneezing power. To finish, add all the ingredients to a quart of high-proof alcohol and mix in the tobacco leaves.

The snuff user then bought whatever quantity of the mixture he or she desired and stored it in a covered jar. To sell wholesale, the Lorillards devised the method of packing the snuff into dried and tanned animal bladders, which they probably got from their brother Jacob.

In addition to their manufacturing skills, the Lorillards were innovative advertisers. Like other manufacturers, their father Pierre first advertised through word of mouth, newspapers, and window displays. But, ever in search of competitive advantage, the next generation took to direct mail campaigning. They printed broadsides itemizing their products and sent them to postmasters throughout the United States, who promptly spread the word. When unethical competitors started using these broadsides to push their own inferior products, the Lorillards created private labels and branded theirs according to quality. The labels themselves soon became commodities and were collected as trading cards. Some were pretty racy. For example, Magdalen Smoking Tobacco featured a buxom young woman with flowing hair lying down on cushions. Others had racist overtones. Century Fine Cut depicted Nature, represented by an angelic white woman, delivering tobacco to a seated, passive Native American surrounded by chattering monkeys. The Lorillards came up with still one more invention when dealers in chewing tobacco tried to pass off their “plugs” as a Lorillard brand. They

made discs out of tin, stamped them with a brand name, and clamped one on each plug. Some of these “tin tags” carried anodyne labels like Good Smoke, but others bore more dubious names like Climax.

6

His income was decent and his job assured, but did Peter Ray ever wonder whether he was compromising his deeply held abolitionist principles by relying on the patronage of white manufacturers who traded in a slave crop? It was slaves who produced the tobacco, first picking it in fields, then slinging hogsheads onto boats and hauling them up and down the river.

7

It was his employers who bought the crop from slave owners, and then cultivated them as customers when they came north for the summer by advertising directly to them in

DeBow’s Review.

Did Ray find the Lorillard advertisements, with their suggestive racist and sexual overtones, offensive to his moral sensibilities? Did he worry that he was betraying his temperance beliefs? Worldly Knickerbockers like Grant Thorburn defended the pleasures of smoking, freely confessing to “enjoying the cheap and sober luxury of a pipe.” But many African Americans and abolitionists were temperance men and women, who decried the use of stimulants as yet another form of enslavement. They railed against alcohol and tobacco alike. “Tobacco and Rum!” the white abolitionist Gerrit Smith fumed in a letter to the

Liberator.

“What terrible twin brothers! What mighty agents of Satan! What a large share of the American people they are destroying!”

8

I don’t know the answer to these questions, and I certainly don’t judge Ray. He had a family to feed, and a community to take care of. He put his money to good use, giving liberally to St. Philip’s and supporting black education.

And the Lorillards were good employers. They hired black workers. They provided housing for Peter Ray in a framed dwelling above their Wooster Street store, as well as homes for those who worked at the snuff mill in Westchester County. When they moved their factory to Jersey City, they set up an evening school for the young and opened a library, today’s Jersey City Public Library. The working conditions of their employees stood in stark contrast to cigar shops of the period in which tobacco, food, and bedding were all jumbled in one room where men, women, and child laborers all worked, ate, and slept.

9

Evidently, Peter Guignon did not have Ray’s success in the “segar” business, because he soon switched trades. He’s listed in the city directory as a hairdresser from 1847 to 1854. The 1850 census records him as living and working at 250 Greenwich Street. His household included Cornelia, his daughter Elizabeth, and the newest addition to his family, Peter Jr., as well as three young men who were also barbers.

Again, I can’t explain the motives behind Peter’s choice of trade except to say that maybe the Guignons intervened a second time, turning to their friends, the former

grand blanc

slaveholding Bérard family who, like them, had left Saint-Domingue at the time of the revolution and settled in New York. They brought with them several slaves, one of whom was young Pierre Toussaint. Emancipated in 1807, Toussaint became a hairdresser, built a thriving business, and bought property. He first rented space from the well-known tanning merchant Abraham Bloodgood on Reade Street before buying his own homes on Church Street and then Canal Street. Toussaint invested his profits in several of the city’s fire insurance companies and, when the Great Fire struck in 1835, he lost 95 percent of his net worth, as much as $900,000 in today’s money. Ever patient and long-suffering, he slowly rebuilt.

Toussaint succeeded because he was a beneficiary of white largesse, though in ways quite different from Ray. Despite the fact that he had been their slave, Toussaint remained loyal to the Bérards and their circle of friends, even paying off their debts when they lost everything in the revolution. It might be hard for us to understand such behavior but, like Ray, Toussaint had few options. He wasn’t about to return to his homeland, which had already disintegrated into chaos. His French friends discouraged him from moving to Paris, where hairdressing was done largely within the household and business opportunities were limited. So he stayed put, shrewdly turning his friendship with the city’s white elite families into a veritable money-making machine.