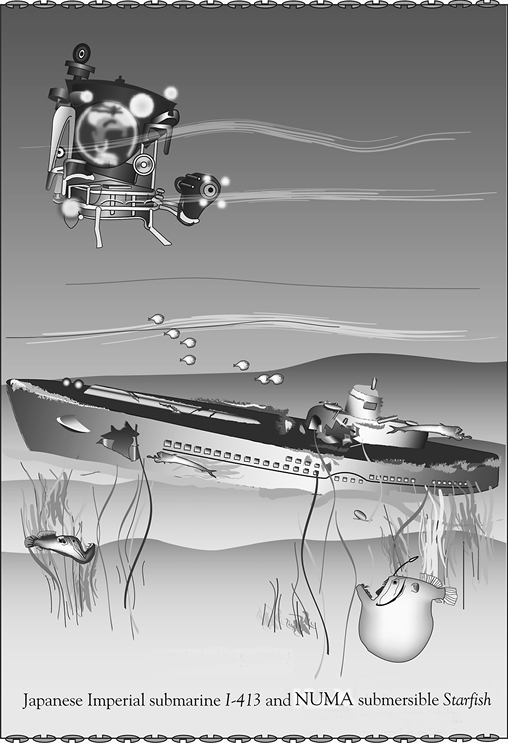

Black Wind (11 page)

Authors: Clive Cussler

“You never did tell us what you found,” Giordino said, raising a dark eyebrow at the biologist.

“Yes, you said you did identify toxins in the water, didn't you?” Biazon asked anxiously. “What was it that you found?”

“Something I've never encountered in salt water before,” she replied, shaking her head slowly. “Arsenic.”

13

T

HE CORAL REEF EXPLODED

with a rainbow of colors arranged in a serene beauty that put a Monet landscape to shame. Bright red sea anemones waved their tentacles lazily in the current amid a carpet of magenta-colored sea sponges. Delicate green sea fans climbed gracefully toward the surface beside round masses of violet-hued brain coral. Brilliant blue starfish glowed from the reef like bright neon signs, while dozens of sea urchins blanketed the seafloor in a carpet of pink pincushions.

Few things in nature rivaled the beauty of a healthy coral reef, Pitt reflected as his eyes drank in the assortment of colors. Floating just off the bottom, he peered out his faceplate in amusement as a pair of small clown fish darted into a crevice as a spotted ray cruised by searching for a snack. Of all the world's great dive spots, he always felt it was the warm waters of the western Pacific that held the most breathtaking coral reefs.

“The wreck should be slightly ahead and to the north of us,” Giordino's voice crackled through his ears, breaking the tranquility. After mooring the

Mariana Explorer

over the site of the maximum toxin readings, Pitt and Giordino donned rubberized dry suits with full faceplates to protect them from potential chemical or biological contamination. Dropping over the side, they splashed into the clear warm water that dropped 120 feet to the bottom.

The readings of arsenic in the water had been startling to everyone. Dr. Biazon reported that arsenic seepage had been known to occur in mining operations around the country and that several manganese mines operated on Bohol Island, but added that none were located near Panglao. Arsenic was also utilized in insecticides, the NUMA biologist countered. Perhaps an insecticide container was lost off a vessel, or intentionally dumped? There was only one way to find out, Pitt declared, and that was to go down and have a look.

With Giordino at his side, Pitt checked his compass, then thrust his fins together, kicking himself at an angle across the invisible current. The visibility was nearly seventy-five feet and Pitt could observe the reef gradually rising to shallower depths as he glided just above the bottom. His skin quickly began to sweat under the thick dry suit, its protective layer providing more insulation than was required in the warm tropical waters.

“Somebody turn on the air-conditioning,” he heard Giordino mutter, verbalizing his own sentiments.

With eyes aimed forward, he still saw no signs of a shipwreck, but noted that the coral bottom rose up sharply ahead. To his right, a large underwater sand dune boiled up against the reef, its rippled surface stretching beyond Pitt's field of vision. Reaching the coral uplift, he tilted his upper body toward the surface and thrust with a large scissors kick to propel himself up and over its jagged edge. He was surprised to find that the reef dropped vertically away on the other side, creating a large crevasse. More surprising was what he saw at the bottom of the ravine. It was the bow half of a ship.

“What the heck?” Giordino uttered, spotting the partial wreckage of the ship.

Pitt studied the partial remains of the ship for a moment, then laughed through the underwater communication system. “Got me, too. It's an optical illusion. The rest of the ship is there, it's just buried under the sand dune.”

Giordino studied the wreck and saw that Pitt was right. The large sand dune that affronted the reef had built up partway into the crevasse and neatly covered the stern half of the ship. The current swirling through the crevasse had halted the onslaught of the sand at a point amidships of the wreck in a nearly perfect line, which gave the impression that only half a ship existed.

Pitt turned away from the exposed portion of the ship, swimming over the empty sand dune for several yards before it dropped sharply beneath him.

“Here's your propeller, Al,” he said, pointing down.

Beneath his fins, a small section of the ship's stern was exposed. The brown-encrusted skin curved down to a large brass propeller, which protruded from the sand dune like a windmill. Giordino kicked over and inspected the propeller, than swam up the sternpost several feet and began brushing away a layer of sand. From the curvature of the stern, he could tell that the ship was listing sharply to its port side, which was also apparent from the exposed bow section. Pitt floated over and watched as Giordino was able to expose the last few letters of the ship's name beaded onto the stern.

“Something

MARU

is the most I can get,” he said, struggling to trench into a refilling hole of sand.

“She's Japanese,” Pitt said, “and, by the looks of the corrosion, she's been here awhile. If she's leaking toxins, it would have to be from the bow section.”

Giordino stopped digging in the sand and followed Pitt as he swam toward the exposed front of the ship. The vessel eerily emerged again from the sand dune at its main funnel, which jutted nearly horizontally, its top edged meshed into the coral wall. From its small bridge section and long forward deck, Pitt could see that the vessel was a common oceangoing cargo ship. He judged her length at slightly more than two hundred feet. As they swam over the angled topside, he could see that the main deck had vanished, its wooden planking disintegrated long ago in the warm Philippine waters.

“Those are some ancient-looking hoists,” Giordino remarked, eyeing a small pair of rusty derricks that reached across the deck like outstretched arms.

“If I had to guess, I'd say she was probably built in the twenties,” Pitt replied, kicking past a deck rail that appeared to be made of brass.

Pitt made his way along the deck until he reached a pair of large square hatch covers, the capstones to the ship's forward cargo holds. With the freighter's heavy list, Pitt had expected to find the hatch covers pitched off the storage compartments, but that wasn't the case. Together, the two men swam around the circumference of each hatch, searching for damage or signs of leakage.

“Locked down and sealed tight as a drum,” Giordino said after they returned to their starting point.

“There must be a breach somewhere else.”

Silently finishing his thought, Pitt slowly ascended until he could look down the curving starboard side and exposed hull. Surrounding the ship, the coral reef rose sharply on either side. Following his instincts, he swam down the starboard hull all the way to the partially exposed keel line, then moved slowly toward the bow. Kicking just a short distance, he suddenly halted. Before him, a jagged four-foot-wide gash stretched nearly twenty feet down the starboard hull to the very tip of the bow. The sound of whistling burst through his ears as Giordino swam up and surveyed the gaping wound.

“Just like the

Titanic

,” he marveled. “Only she scraped herself to the bottom on a coral head instead of a chunk of ice.”

“She must have been trying to run aground on purpose,” Pitt surmised.

“Outrunning a typhoon, probably.”

“Or maybe a Navy Corsair. Leyte Gulf is just around the corner, where the Japanese fleet was decimated in 1944.”

The Philippine Islands were a hotly contested piece of real estate in World War II, Pitt recalled. More than sixty thousand Americans lost their lives in the failed defense and later recapture of the islands, a forgotten toll that exceeded the losses in Vietnam. On the heels of the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces had landed near Manila and quickly overrun the U.S. and Philippine forces garrisoned at Luzon, Bataan, and Corregidor. General MacArthur's hasty retreat was followed by three years of Japanese oppressive rule, until American advances across the Pacific led to the invasion of the southern island of Leyte in October 1944.

Just over a hundred miles from Panglao, the province of Leyte and its adjoining gulf was the site of the largest air/sea battle in history. Days after MacArthur and his invasion force landed on Leyte, the Japanese Imperial Navy appeared and successfully divided the American supporting naval force. The Japanese came within a hair of destroying the Seventh Fleet, but were ultimately turned back in a devastating defeat, losing four carriers and three battleships, including the massive battlewagon

Musashi

. The crippling losses finished the Imperial Navy's brief dominance in Pacific waters and led to the country's military collapse within a year.

The sea channels surrounding the southern Philippine islands of Leyte, Samar, Mindanao, and Bohol were littered with sunken cargo, transport, and warships from the conflict. It would be no surprise to Pitt if the toxins were related to combat wreckage. Eyeing the gash in the cargo ship's hull, it was easy to presume that the vessel was a victim of war.

Pitt mentally envisioned the Japanese-flagged freighter under air attack, the desperate captain electing to run the ship aground in a perilous attempt to save the crew and cargo. Slicing into the coral reef, the bow quickly filled with water as the ship ricocheted off the sides of the crevasse. With a full head of steam, the ship literally drove itself over onto its port side. Whatever cargo the captain had tried to save lay hidden and dormant for decades to follow.

“I think we definitely hit the jackpot,” Giordino said in a morose tone.

Pitt turned to see Giordino's gloved hand pointing away from the hull and toward the adjacent reef. Gone was the vibrant red-, blue-, and green-colored corals they had witnessed earlier. In a fan-shaped pattern stretching around the ship's bow, the coral was uniformly tinted a dull white. Pitt grimly noted that no fish were visible in the area as well.

“Bleached dead from the arsenic,” he noted.

Turning back to the wreck, he grabbed a small flashlight clipped to his buoyancy compensator and ducked toward the gap in the hull. Edging his way slowly into the ship's underside, he flicked on the light and sprayed its beam across the black interior. The lower bow section was empty but for a mass of thick anchor chain coiled in a huge pile like an iron serpent. Creeping aft, Pitt moved toward the rear bulkhead as Giordino slipped through the gash and followed behind him. Reaching the bulkhead, Pitt panned his light across the steel wall that separated them from the forward cargo hold. At its lower joint with the starboard bulkhead, he found what he was looking for. The pressure from the outer hull's collision with the reef had buckled one of the plates on the cargo hold's bulkhead. The bent metal created a horizontal window to the cargo hold several feet wide.

Pitt eased up to the hole, careful not to kick up silt around him, then stuck his head in and pulled in the flashlight. A huge lifeless eye stared back at him just inches away, nearly causing him to recoil until he saw that it belonged to a grouper. The fifty-pound green fish drifted back and forth across the compartment in a slow maze, its gray belly pointing up toward the trail of Pitt's rising exhaust bubbles. Peering past the dead fish into its black tomb, Pitt's blood went cold as he surveyed the hold. Scattered in mounds like eggs in a henhouse were hundreds of decaying artillery shells. The forty-pound projectiles were ammunition for the 105mm artillery gun, a lethal field weapon utilized by the Imperial Army during the war.

“A Welcome-to-the-Philippines present for General MacArthur?” Giordino asked, peering in.

Pitt silently nodded, then pulled out a plastic-lined dive bag. Giordino obliged by reaching over and grabbing a shell and inserting it in the bag as Pitt sealed and wrapped it. Giordino then reached over and picked up another highly corroded shell, holding it just a few inches off the bottom. Both men looked on curiously as a brown oily substance leaked out of the projectile.

“That doesn't resemble any high-explosives powder I've ever seen,” he said, gingerly setting the weapon down.

“I don't think they are ordinary artillery shells,” Pitt replied as he noted a pool of brown ooze beneath a nearby pile of ordnance. “Let's get this one back to the shipboard lab and find out what we've got,” he said, carrying the wrapped ordnance under his arm like a football. Gliding forward along the bow section, he slipped through the open hull and back into the bright sunlit water.

Pitt had little doubt that the armament was a lost World War II cache. Why the arsenic, he did not know. The Japanese were innovative in their weapons of war and the arsenic-laced shells might have been another device in their arsenal of death. The loss of the Philippines would have effectively spelled the end of the war for the Japanese and they may have prepared to use the weapons as part of a last-gasp measure against a determined enemy.

As they surfaced with the mysterious shell, Pitt felt a strange sense of relief. The deadly cargo that the ship carried so many years ago had never reached port. He was somehow glad that it had ended up sunk on the reef, never to be fielded in the face of battle.

Part 2

C

HIMERA