Blood and Guts (18 page)

Authors: Richard Hollingham

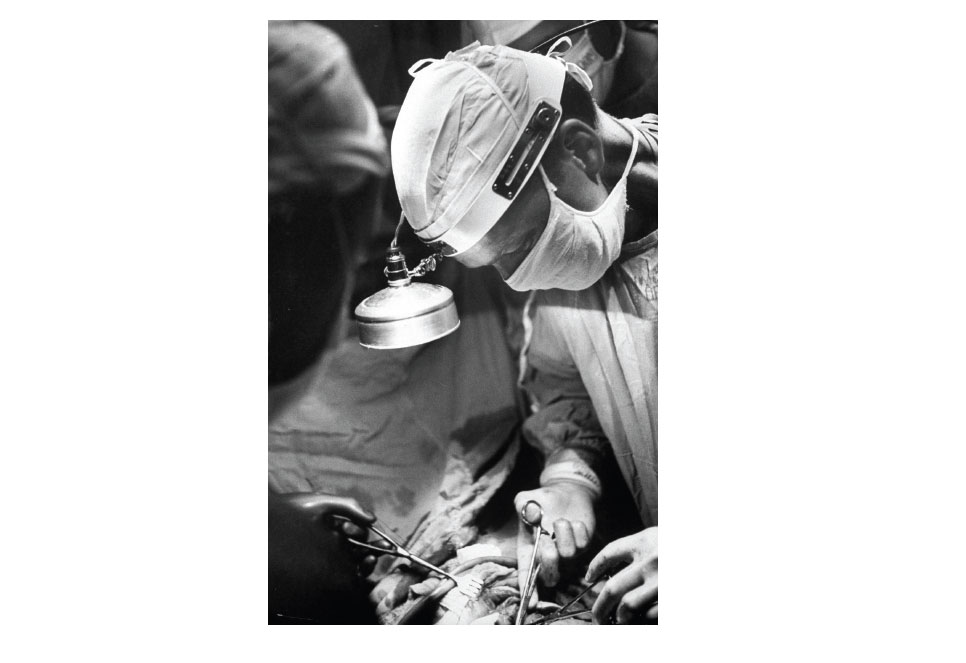

Walter Lillehei operating on a

beating human heart.

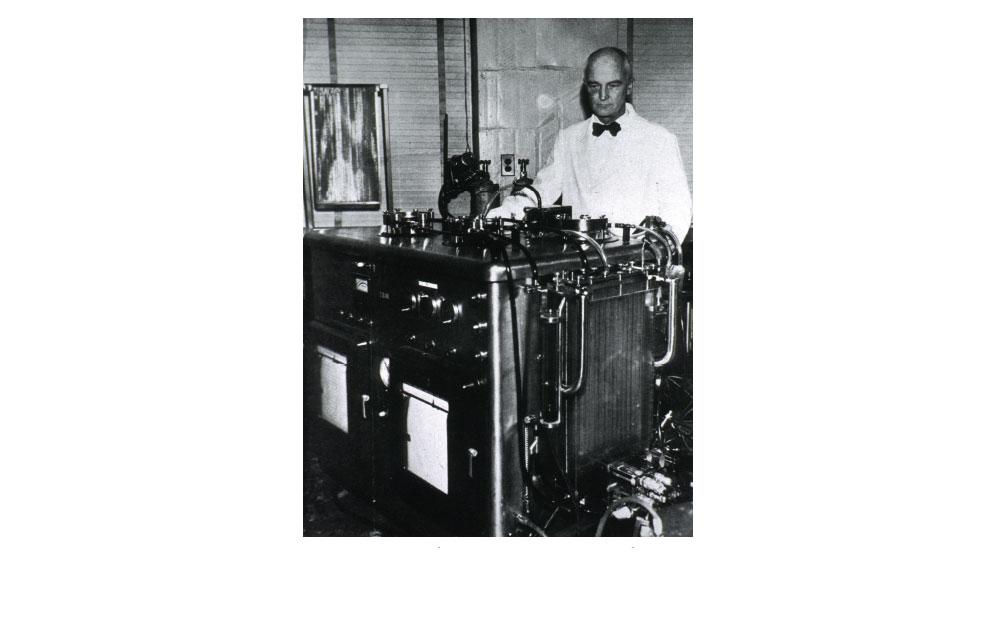

One of the few pictures ever taken

of John Gibbon with his fearsome looking

heart-lung machine. At the top left of the

machine is the screen where the blood

was oxygenated.

Christiaan Barnard with the world's first heart transplant patient, Louis Washkansky,

in 1967. The plastic sheet was used to help protect Washkansky from infection.

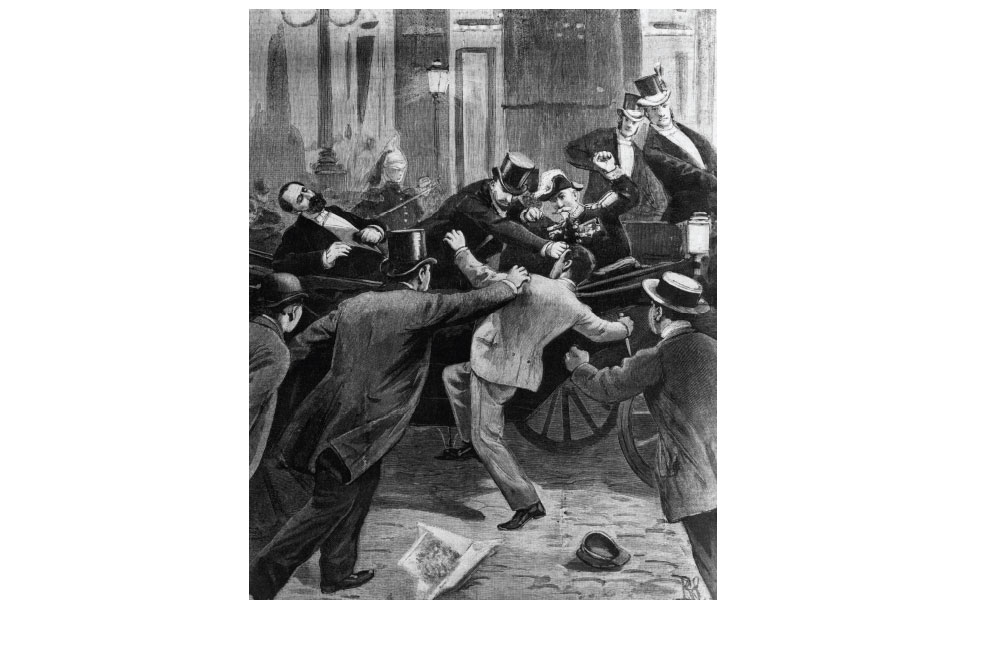

The dramatic assassination of

President Sadi Carnot on 25 June 1894.

The murderer is being grabbed by the

crowd as he attempts to make his escape.

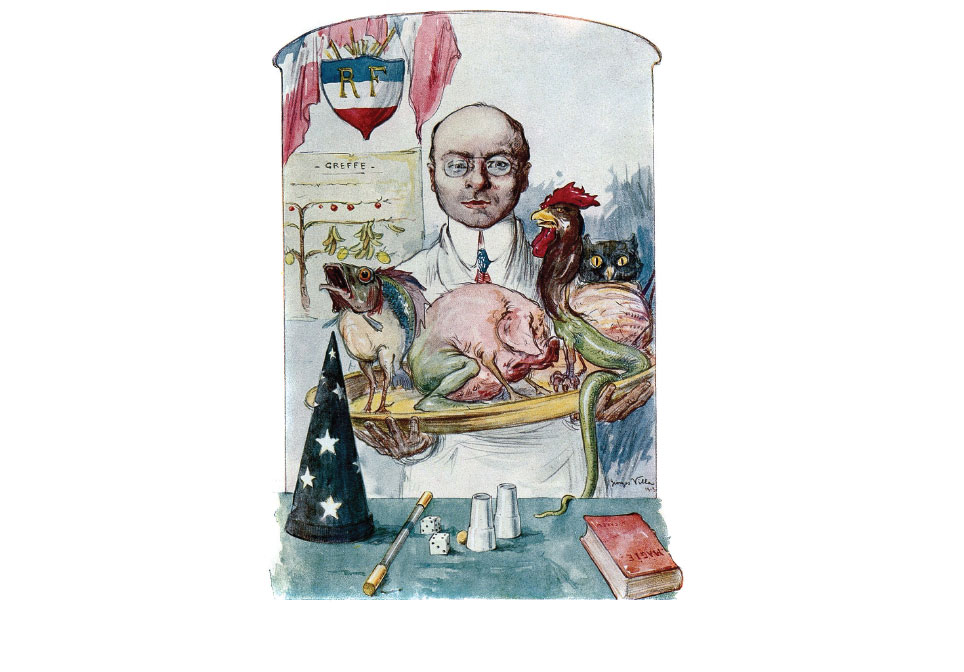

The weird and wonderful world of

Alexis Carrel in an illustration taken from a

French periodical. It's difficult to tell whether

they were proud of their countryman.

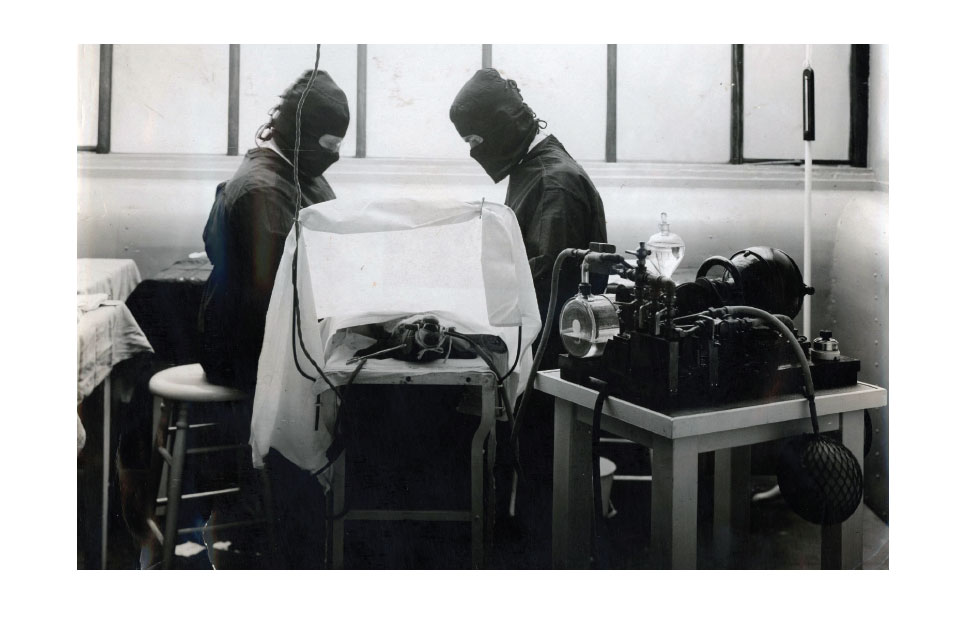

Another experiment in the laboratories of Alexis Carrel. Heaven knows what is

going on behind the sheet. This picture is undated, but was probably taken in the 1930s.

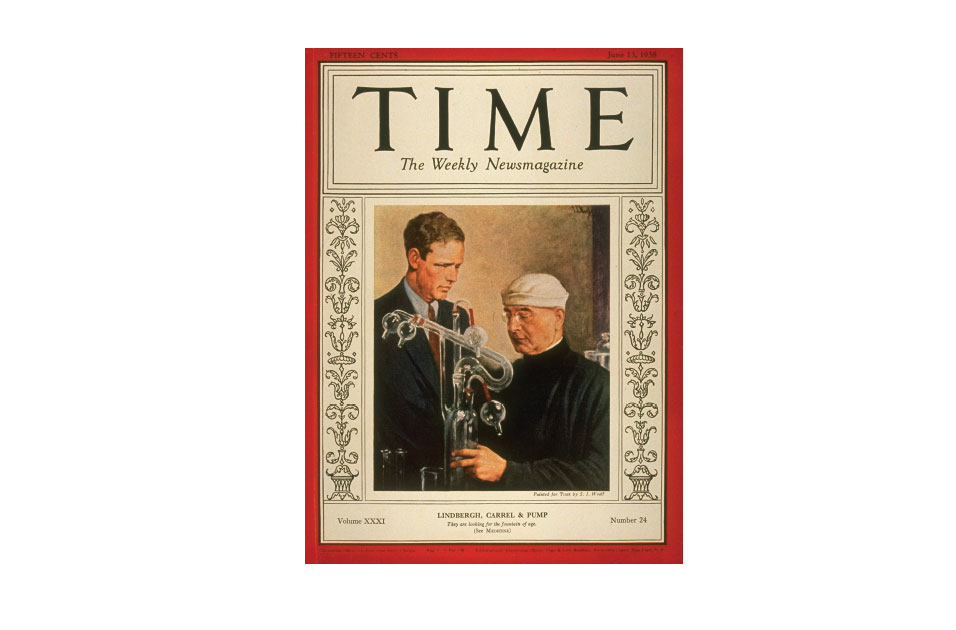

Alexis Carrel and

Charles Lindbergh make the

cover of

Time

magazine in

June 1938. Not long afterwards,

their reputations would go

into freefall.

The appalling result of Vladimir Demikhov's 1959 operation

to transplant the head of a puppy onto the head of another dog.

Richard Herrick is

wheeled out of hospital

by his identical twin

brother, Ronald, on

19 January 1955.

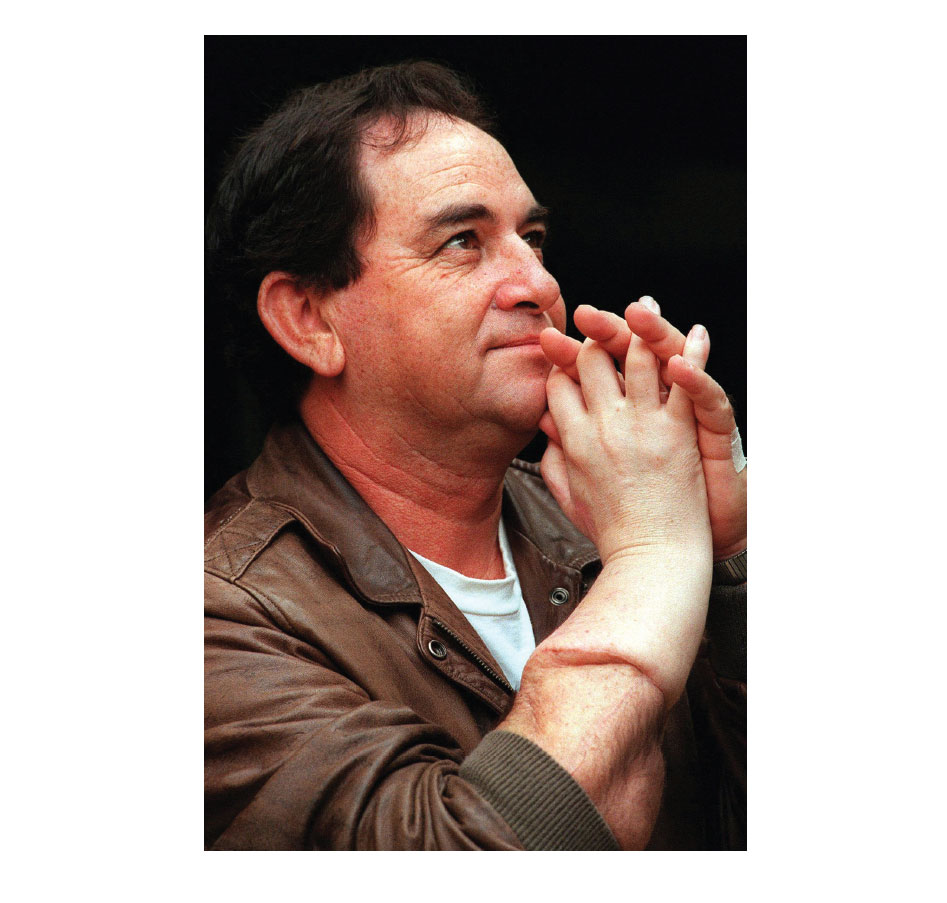

Clint Hallam enjoying the

use of his recently transplanted

hand in 1998. Even before

Hallam's body started to reject

the transplant, its appearance

was disconcerting.

DEAD MAN'S

HAND

THE STORY OF A TRANSPLANT

March 2000

From a distance, there was something odd about New Zealander

Clint Hallam. When he walked towards you it became obvious that

one arm was longer than the other. Up close the arm was even more

disturbing, verging on the grotesque. Anyone who saw his hand

would remember it for ever, perhaps in their nightmares.

Hallam recalls sitting in an aircraft next to a nice old lady. They

got talking. The lady recognized Hallam from somewhere, but

couldn't quite place him. Then she happened to glance down at his

right hand. Recoiling in shock, she pressed the call button to

summon the flight attendant and asked to be moved to another

seat. The lady turned to Hallam to apologize. She said she had nothing

against him personally, only she couldn't bear sitting next to

someone who was wearing a dead man's hand.

One of Hallam's close friends made a similar confession. Hallam

could never understand why, when they met, his friend would always

grasp Hallam's wrist rather than shake his hand. Hallam reckoned it

was an act of kindness, to avoid any risk of injury to his limb. When

he asked about it, his friend confessed to finding Hallam's hand

quite horrific. He wasn't the only one. The recipient of the world's

first hand transplant was beginning to realize that many people

found his new hand repulsive. Now, eighteen months after the

operation, even Hallam was beginning to have some doubts.

From the shoulder down, the upper part of Hallam's right arm

was perfectly normal. Its skin tone matched Hallam's dark complexion

and was covered in black hairs and dotted with freckles. Then,

just beyond the joint of the elbow, there was a sharp division where

the skin became pale and practically hairless. It was as if Hallam

was wearing a long white glove. There was a bulge – a swelling –

where the brown skin met the white. It was a long white glove that

didn't quite fit.

The underside of Hallam's lower right arm was bruised and

damaged. The skin was inflamed, raw and angry – as if he had been

burnt. Beyond the wrist the hands were similarly swollen. The skin

was peeling; there were ulcers and the flesh was shiny. It looked like

the outer layer of skin had been stripped away. When it came to the

fingers, the decay was even more pronounced. The fingertips were

crusty and sore, the yellow nails gradually separating from the flaking

skin underneath. Small wonder the woman on the plane chose

to move to another seat.

Hallam had received his hand transplant on 23 September 1998

at the Edouard Herriot Hospital in Lyon, France. The operation

took almost fourteen hours and was a brilliant technical achievement.

Earl Owen led a team of some the world's most experienced

transplant specialists from Australia, Britain, France and Italy.

France was chosen to host the operation because of its laws on organ

donation. There you have to opt out of donating your body to medicine,

rather than opting in. As a result, almost everyone who dies

becomes a potential donor, so many more donors are available –

perfect if you are waiting for a new arm and hand.

The donated limb came from that all too frequent source of

body parts – a motorcyclist. The limb was matched for blood type

and tissue type, but, as it turned out, not appearance.

The surgical technique used to join together Hallam's stump

and the dead motorcyclist's lower arm is known as microsurgery and

is fantastically intricate. The surgeons wore powerful magnifying

lenses and employed precise instruments, tiny needles and the

finest of threads.

First they joined together the two bones of the forearm to hold

the limb stable. Then they connected the blood supply – the arteries

and veins – to keep the tissue alive. Once the blood was flowing,

they stitched together the muscles and tendons and reconnected

the nerves. Finally, the surgeons were able to join together the skin.

At the inevitable press conference held shortly after the operation,

Owen described himself as 'very happy'. It was a moment of

surgical glory. 'We all have big smiles,' he said, and gave the operation

a fifty-fifty chance of long-term success. Others were equally

enthusiastic. Eminent British transplant surgeon Nadey Hakim

called it an 'incredibly exciting breakthrough,' adding, 'to see a

man restored with an arm is tremendously satisfying'.

The new arm had to be kept immobile for a few weeks while the

graft healed, but everyone was optimistic that the patient would

develop the full use of his limb. Hallam himself was overjoyed. It was

incredible to see fingertips at the end of his arm again. With a new

hand, he had been given a new life. It was a surgical miracle.

Hallam had spent years waiting for the operation. He lost his

original hand in an accident with a circular saw in 1984 while he was

serving time at a prison in New Zealand.

*

His severed hand had

been sewn back on, and although it looked OK, it had little function

and was all but useless. A few years later Hallam decided to get rid

of the hand altogether and opted instead for a prosthetic limb. This

hadn't worked out either, and he told the BBC that he had never

been able to accept having a lump of plastic attached to his arm. It

was not natural. Perhaps one day the technology would be available

for a hand transplant.

*

The circumstances of the injury remain somewhat vague. The surgeons who carried out the

1998 transplant operation were unaware that Hallam had sustained the injury in prison.

Hallam's somewhat chequered past was revealed by the media following the operation. This

did little to endear Hallam to the surgical team. Owen said later that although they had

conducted psychiatric tests, they should have looked more closely into Hallam's background.

However, a few months after the 1998 operation Hallam was

struggling to overcome his disappointment. It wasn't just the obvious

mismatch between his new arm and the old one, so much as the

practicalities. The new arm did not work very well. There was only

limited movement: Hallam could move the limb and bend his new

fingers to a limited extent, but he said he was almost more crippled

with the hand than he had been with a stump.

There was a marked contrast between Hallam's experiences and

the surgeon's rhetoric. They were claiming the operation as a great

success and told the media how Hallam could grab things, pick up a

glass and even write with a pen. They were also pleased that he could

feel pain and temperature on both sides of the new grafted hand.

But they weren't the ones who had to deal with the side effects.

To avoid the transplanted limb being rejected by his body's

immune system, Hallam had to take a cocktail of different drugs.

There could be eleven tablets to swallow in the morning, four at

lunchtime and eleven more in the evening. The exact amount

varied from week to week, but Hallam was usually being prescribed

some combination of steroids, anti-rejection tablets and immuno-suppressants

– drugs that, as the name suggests, suppressed his

immune system. He was also taking pills to help his fingernails

recover. Every day he had to count out the various tablets to make

sure he didn't take too many or too few. The pills were keeping his

arm alive, but they were also having other effects. Hallam had

started to develop diabetes and needed to take insulin to control his

blood sugar. Physically, he was also changing. Hallam was used to

keeping fit and had been in reasonably good shape. Now he found

he was growing breasts. Worse, the powerful drugs increased his risk

of developing cancer.

And it was not just the physical limitations that were taking their

toll. Hallam was beginning to realize that there was a psychological

price to pay for having a dead man's hand attached to his body.

Aside from the mental anguish for any man of growing breasts, the

transplant increasingly looked and felt like it did not belong. Other

people would comment, saying how white the transplant looked, or

how the new hand was smaller than the other one. Hallam realized

how angry he was with the doctors for not waiting for a hand

that was better matched. It was as if, he said, they were more interested

in the transplant than the person. He had dreamt for years

of having a new hand, but the reality was proving increasingly

uncomfortable. What happened next became inevitable.

By 2001, Hallam had begun to take fewer and fewer of his

prescribed drugs. Every time he got sick his immune system struggled

to cope, so he decided the answer was to cut down on the

immuno-suppressants, but the effect on his hand was hideous.

Attacked by his own body's immune system, the limb had all but

died; the flesh was rotting away on the end of Hallam's arm. He

had lost all feeling; it was a wonder the infection hadn't spread to

other parts of his body. Hallam told the BBC he felt 'mentally

detached' from the hand. He had had enough and begged the

doctors to remove it.

In February 2001 Clint Hallam's hand was amputated by Nadey

Hakim, one of the surgeons who had helped attach it in the first

place. The procedure, at a private London clinic, took ninety

minutes. Hallam was relieved to see it gone. Some of the surgeons

who had enjoyed such acclaim only a few years before were angry

that their work had been in vain; that their patient had not persisted

with his medication.

In retrospect, Clint Hallam was probably the wrong person to

receive the world's first hand transplant. If he had done exactly what

he was told – had taken his medication, had followed doctor's

orders – he might still be walking around with a dead man's hand.

Even so, he would have had to cope with the physical symptoms, the

strict drug regime and probably a shorter lifespan as a result of

diabetes or perhaps cancer. Eight years after his transplant, Hallam

was once again fitted with an artificial limb. He claims he has no

regrets about having the transplant; his only regret is being the first.

The case of Clint Hallam illustrates the barriers that have to be

overcome for successful transplantation – whether it is the transplantation

of a hand, finger, kidney or heart. The first barrier is

simply one of technique. It has taken more than a century to

develop the surgery of transplantation. Stitching together blood

vessels is difficult enough, let alone trying to join muscles, tendons

and nerves. But the operation itself is only the start. Next there is

the enormous problem of rejection. The body's immune system will

fight any alien tissue. Even with the latest drugs, rejection is still a

major hurdle for transplant surgeons.

The final problem is more subtle, and is downplayed or ignored

by surgeons at their peril. Any transplantation involves overcoming

a psychological barrier. What is the effect of having a dead man's

hand transplanted on to your arm? It certainly bothered that

woman on the plane. Did Hallam ever think about the motorcyclist

who had died? Before the transplant that hand had been gripping a

motorcycle handle – an essential part of a whole different human

being. What about the psychological effects of a kidney or heart

transplant or even a face?

The surgeons who had operated on Clint Hallam had overcome

the technical problems. Until he stopped taking them, the drugs

had countered his body's physical rejection. But the surgeons had

failed to overcome the final barrier. Consciously or not, it was

Hallam himself who had rejected the hand.

James Spence (and Sons), Soho, London, 1765

James Spence was always very discreet. No one, he assured the

young lady, need ever know that she had visited him. Of course,

nowadays he rarely conducted these procedures himself. He left

most of the day-to-day work to his sons. However, for this fine lady

he would make an exception. She was fearful of going to see anyone

else (there were so many charlatans about these days). Spence had

already established the finest reputation in London for pulling

teeth, and was proud to call himself a dentist, even though

'dentistry' was only just starting to establish itself as a respectable

profession. There was no one better to go to for a tooth transplant.

Spence preferred to use living donors for his tooth transplants.

They were easy to come by and it avoided the repulsion many

people felt at the idea of eating food with teeth from the dead. Mind

you, teeth taken from cadavers were a lot cheaper, and many

dentists did a roaring trade in teeth extracted from the mouths of

soldiers killed on the battlefield.

Nevertheless, today Spence needed teeth from the mouths of

young women. Earlier that morning he had dispatched a servant to

locate suitable donors in the neighbourhood – women who would

be willing to give up their front teeth. They would be handsomely

rewarded (well, it would be handsome to them; the expense would

make only a small dent in Spence's substantial profit margin). By

mid-morning, several young women were queueing in the alley

behind Spence's offices. He planned to take a few teeth, maybe a

couple from each woman, to see which ones produced the best fit.

His patient arrived accompanied by a friend for support.

Spence ushered the women into his consulting room. The patient

sat down on one of the plush, high-backed leather chairs. At first

glance she was something of a beauty and would, he thought, have

no shortage of suitors. But when he took a look at her mouth he

realized it was little wonder she had come to him for help. Her teeth

were in a terrible state. Her mouth stank of decay, with black rotten

stumps emerging from raw, inflamed gums. She was worried about

the pain she was going to experience. Spence reassured her that she

would hardly feel anything; he stopped himself from telling her that

most of the pain would be experienced by the donors.