Blood and Iron (30 page)

Authors: Tony Ballantyne

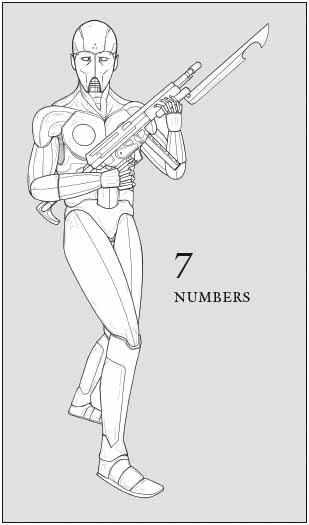

Now he had reached the place where the columns divided, and he followed the left-hand stream. To his side he saw, not four hundred yards away, the edge of the first moat. And beyond that, the grey bodies of infantryrobots, marooned there to fight him and his army. They just stood and gazed at the seemingly endless stream of robots that marched past them. No one on the moat raised a gun in challenge, nor did any members of the Uncertain Army.

Kavan marched on, following the length of the iron wall to his right. From the ramparts, more robots gazed down at him, their gradually darkening silhouettes lit by the golden light behind them.

A flash of silver, and Calor appeared at his side.

‘Something’s up, Kavan. They just stand there, watching us.’

‘They’ll be hoping to settle this by words,’ replied Kavan.

The robots ahead were coming to a halt; a wave of stationary metal seemed to travel back through the moving stream.

Kavan, Ada, Calor, Goeppert and the rest stopped. They turned to face the city.

‘Now what?’ asked Calor.

Kavan looked to the left and right, searching for any signs of weakness in the seemingly impassable wall. There were none. For the moment.

‘Now what?’ repeated Calor.

‘Is there any question about it?’ said Kavan. ‘Now we attack.’

Susan

Years ago, Karel had told her about the Centre City, long before the war had come to Turing City State.

‘It’s the

utility

of the place, Susan,’ he had said, eyes glowing as he remembered his recent trip. ‘Everything is just iron and steel and brick. There is no decoration, no paint, save what they use to keep the rust at bay. I walked down streets surrounded by grey and green and blue robots, and I saw nothing there that didn’t have a purpose.’

‘They’ll be making a point,’ Susan had said. ‘It won’t be the same inside the buildings, you can trust me on that!’

‘No, you don’t understand! That’s not the way they think in Artemis City. To them, everything is bent towards Nyro’s purpose.’

‘That will be what they say,’ laughed Susan. ‘There will be some variation in the way their minds are twisted. There always is! Listen to me, I’m a mother. I know what it’s like to make a mind. There’ll be decoration somewhere in that city. And even brutal utilitarianism is a sort of aesthetic statement.’

‘I realize that. But it’s different there, Susan. They really believe in what they’re doing!’

‘Most of them will,’ Susan agreed. ‘But anyway, I don’t like you going there Karel. I don’t like what Artemis City is doing. They say they are going to attack Wien!’

‘They may do.’ Karel had been suddenly serious. ‘But that’s the way they think. It’s the way their minds are twisted. That’s what I’m trying to explain!’

‘Then I don’t like the way their minds are twisted.’

‘Well, at least they are true to themselves. You can see it in their Centre City. You’d understand if you could see it for yourself.’

‘Well, I don’t think I ever will . . .’

But she had been wrong on both counts. Here she was now, thought Susan, and look, Karel had been right.

The Centre City was well made, but it was utilitarian from top to bottom. The road was constructed of good brick, as were the walls. There were steel and iron pillars and doors, steel window frames and guttering and copper tiling, and that was it. It wasn’t like the centre of Turing City, where metal had leaped in loops and arches, and stained glass and copper and brass chasing had decorated every surface. The paint in Turing City had been of all colours; here, if paint was used at all, it was the same standard red lead, splashed onto the metal with little waste but little care.

There was a stillness in the middle of the Centre City. Occasionally she would see a figure, hurrying along in the distance, or a door would open and shut further down the street, and a clerk of some kind would come dashing past.

One of them had called out, ‘Kavan is here!’ as he hurried by, three rolls of foil tucked beneath his arm. The panelling around his legs was loose, as if he had been suddenly called away while tending himself. She watched him go, and then turned and resumed her wandering through the streets.

This was where the computers worked, she knew. This was where the calculations were performed that balanced metal coming into the city with robots walking out. All the numbers that modelled the Artemisian State were brought here on sheets of foil: tons of coal mined, yards of railway line laid, gallons of petroleum refined, number of robots built, number of robots conscripted . . . All of these were added and multiplied, means and standard deviations calculated, regression lines plotted on yet more sheets of foil, and then reports were compiled, the mass of data reduced to a few lines of figures and graphs, and then those results inscribed on yet another sheet of foil that would be passed to the leaders of Artemis, that they could better decide their future strategy.

Susan understood all that, it was what she used to do back in Turing City, though for very different reasons. There it had been about maximizing happiness. There they hadn’t exactly tried to put a number on beauty, but they had least attempted to model curves both on foil and in actual steel that were pleasing to the eye.

Even so, Susan was confident of this: that whatever had happened to Nettie would be logged here somewhere. Somewhere amongst the millions of sheets of foil that resided here would be the record of what had happened to her friend. Find Nettie, and then maybe she would be ready to look for Karel. If he hadn’t found her first.

All she had to do was find the correct sheet.

Another robot came hurrying towards her, his shell painted the green of a computer.

‘Hey,’ she called. ‘I’m looking for Spoole. Where is he?’

‘In the Basilica, I should think. You should try the Main Index, two blocks over,’ said the robot. ‘Though you won’t find anyone to help you there. They’re on a stripped-down staff what with Kavan and everything.’

‘That’s okay, I’ve got my orders.’

‘Really?’ said the other robot, suddenly suspicious. ‘And what are they? Shouldn’t you be on the walls with the other infantry?’

‘No,’ said Susan. ‘And my orders are none of your business. I’ve been sent here on an important job.’

Susan had killed another robot not half an hour ago. At the moment she felt as if she could do anything. Facing down a computer was the least of her worries. She held his gaze.

‘Okay,’ he said, ‘fine. We’ve all got our jobs to do.’ And he hurried off down the road.

Susan set off in the direction he had indicated. The streets seemed hollow, empty of life and movement. Nothing but steel doors set in red-brick walls. One of them opened and another computer appeared. Her courage had not yet deserted her; she decided to bluff it out.

‘I’m looking for Spoole,’ she said.

‘Only one of you?’

‘How many did Spoole expect?’

‘It’s not for me to say,’ replied the computer. ‘But I suppose a robot in his position will be happy with what support he can find. You’d better come this way!’

Vignette had been right, she realized. The Generals really were in disarray. The city was not being properly led at the moment, and that left scope for robots such as herself to move between the spaces.

She followed the computer through the door, down a corridor, into huge room, past lines of desks. A few green-painted robots still sat working at them. Steel styli scratched shapes into the metal foil.

Up one flight of stairs, and then another. She passed more rooms where robots still worked.

‘The sheets pass up the building,’ said the computer, conversationally. Susan had the impression that, to him, the coming war was nothing more than a reason for more foil to be written on. His true world existed in here, all else was just pale shadows. ‘The figures are analysed and reduced on each floor. As they approach the upper levels all that data is changed to information.’

‘Oh,’ said Susan.

The computer touched her elbow, the current in his hand weak.

‘I thought you might like to know,’ he said, smiling all the time, ‘while you’re here and all. People look at Artemis City and all they see is train tracks and infantryrobots, but there is more to this state than that!’ He squeezed the grey metal of her elbow harder. ‘No offence intended, of course.’

‘None taken,’ said Susan as they climbed yet another flight of steps. The robots on this floor seemed slightly better built than the ones below. The foil they worked on was of higher quality, judging by the colour of the metal.

‘These offices are what makes Artemis possible!’ said the robot proudly. ‘Those robots are producing the information that will enable Spoole and General Sandale and the rest to make decisions. But decisions are only part of the story. Okay, there are tactics involved in attacking a city, but that’s not all. You wouldn’t believe what it takes to move guns and troops and supplies and ammunition to the right place! Logistics is the key to Artemisian success!’ His eyes glowed as he spoke, but that glow suddenly faded. ‘Saving the contribution you and the other infantry make of course,’ he added.

They had left the building now. They were walking out across a glass and metal bridge that stretched over the street far below, connecting the computer office with the building opposite. Susan’s gyros lurched when she realized where they were going.

‘Is this the Basilica?’ asked Susan, in wonder.

‘Oh yes!’ said the computer, proudly. ‘This bridge is part of the information superhighway that connects all of the Centre City! Hundreds of sheets of foil a day travel this way!’

They entered the Basilica, and Susan looked around at the decoration that had appeared. Maybe it wasn’t as ostentatious as that of Turing City, but it was there. Gold, silver, platinum, titanium, tungsten, all wrapped around each other, moulded into the walls. Always discretely, austerely, but there nonetheless.

She had been right. The Centre City was a statement after all, and the thought filled her with sadness. She doubted she would ever be able to tell this to Karel.

But these thoughts were pushed from her head as the robot opened a door and led her into a sparsely furnished room. A steel-clad robot stood inside, gazing out of the window. So simple was his appearance that Susan did not realize who it was until the computer spoke.

‘There’s an infantryrobot here to see you, Spoole.’

Kavan

They’d built trenches and walls, thought Kavan. They’d lost already. What would be in those trenches, he wondered. Petrol? Hot oil? What would he put in them?

Kavan knew the answer to that: he wouldn’t have built them in the first place.

‘The trenches can be bridged,’ said Ada.

Kavan looked at the engineer, her blue body streaked with oil. She was loving this, he knew. He could hear it in the rich hum of current that rose from her body.

‘Not yet,’ he said. ‘We’d be cut down by the troops in the middle if we funnelled ourselves in that way.’

‘Well, when you’re ready, just say the word.’ Ada didn’t seem to mind. She was gazing eagerly at the iron wall. ‘Just get me close enough to that. Let me get to work on it.’

‘I will.’ Kavan felt a curious sense of satisfaction. This was what he was made for. He was back in his element again. Something caught his attention.

‘What is it?’ asked Ada, unscrewing the end of a metal cylinder, checking the explosives inside.

‘That Scout.’

‘Yes?’

‘You don’t see many male Scouts, do you?’

‘Something to do with the pattern of the mind,’ said Ada, glancing at the silver robot nearby. ‘It works better when it’s female.’ The robot’s body was as graceful and feminine as any other Scout’s, but there was something about the way that he went through his warm up movements that was unmistakeably male.

‘Why do you ask?’ said Ada. ‘It’s a funny thing to wonder about, just before a battle.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Kavan. ‘We take things for granted, don’t we? Did you ever have children Ada?’

‘No. That’s a job for the mothers of Artemis.’ She gazed at him. ‘Did you ever have children, Kavan?’

‘No. We are all woven with our own purpose.’