Blood and Thunder (38 page)

Authors: Alexandra J Churchill

The tenderness and care that he had lavished on those he was responsible for remained with them for the duration. âMy last memory of Alick,' wrote one colleague who had been maimed back in 1915, âwill be a very characteristic one, of the loving care with which he bandaged me and helped me out of the trench when I was wounded.'

By the end of the war, only one of the three generations remained, for Alick's grandfather died in March 1918. Alick's was just one of the lives wasted on 23 July in more badly orchestrated attacks that gained nothing. He was 24 years old, a fraction older than the age his mother had been when she died bringing him into the world.

Notes

Â

1

Walter and Billy Congreve are one of only three sets of fathers and sons to have been awarded the Victoria Cross. Johnnie Gough and his father were another (his uncle also won the award, meaning that their family has won it more times than any other) and the third pair to have the distinction are Field Marshal Lord Roberts and his son Frederick. Thus four of the six men concerned are Old Etonians.

14

By the summer of 1916, the Guards Division in particular was overflowing with OEs who had little experience outside of school. Straight from Eton, they delivered themselves to barracks ready, but not necessarily willing, to fight. Hundreds of boys who had left Eton

since

1914 were serving in or had already died in the armed services. Hugh MacNaghten was one housemaster finding this incredibly difficult to comprehend. He had seen William Gladstone, grandson of the four-time prime minister of the same name, hovering by the river on leave. He had rowed with the VIII as late as 1916 and with his baby face âhe seemed never to have left at all'.

1

Another such boy was Henry Lancaster Nevill Dundas. He was 17 when the war began and had always stood out in a crowd. Born in Edinburgh in 1897, his passion was reserved for three aspects of his life: Eton, Scotland and, once he had joined the army, the Guards Division. âAbout these things,' he wrote, âI have no sense of humour.'

He was from the outset a vibrant personality, one of a kind. At two years old, during the Boer War, he would entertain adults by singing âRule Britannia' in full (or âThe Absent Minded Beggar' for light relief). Henry liked to shock. One kindly old clerk at Kirkcudbright once asked him how old he was and 4-year-old Henry piped up in the broadest Scotch accent he could muster, âI'm 65 and drunk every night!' He became a well-known face in Edinburgh. Once he failed to turn up for a French lesson with a tutor and was caught instead joyriding on a milk cart about the streets and shouting instructions to two street urchins doing the driving. On another occasion he wandered away from his guardian and they found him turning the handle of a barrel organ whilst the old man who owned it collected the money. He was a fantastic mimic and his father was utterly baffled one day to pass underneath a window at the family home of Redhall and hear a deep baritone pontificating in a sing-song manner. He found his five-year-old son standing on a table in the nursery, wearing his nurse's nightgown and âdeclaiming to an admiring congregation of the servants a sermon in the manner of a parish minister'.

Henry was sent to Horris Hill Preparatory School in Berkshire. His father had loose family ties to Etonian scientific brains such as Jack Haldane and Henry was undoubtedly bright enough to follow them into College at Eton. Indeed he succeeded in making the list of King's Scholars but his parents thought that an Oppidan house, without such a fierce focus on academic achievement, would give their son a broader experience of school life.

Thus in September 1910 Henry entered Hugh Marsden's house. His first years, not unusually, were a trying experience. The elder boys in the house gained some amusement from having Henry sing Harry Lauder songs on demand but Henry had a tendency to mask his self-consciousness by âforcing himself into the centre of the picture'. He could come off as tactless and on occasion full of himself. âExhausting' was a word that one boy used to describe him and several others remarked that he was perfectly likeable, in small doses. His wit and his kindness, though, balanced out his over-exuberant character. Dick Durnford was his classical tutor and a perfect fit. Good natured and patient, he recognised Henry's immense promise beyond his hyperactive nature and lavished much time on him.

As Henry moved through the school and matured into a young man, one school report labelled him as âexceedingly sharp, almost too sharp for the peace of mind of his Divisional Master (doing the writing), whom he bombards with volleys of incisive and often awkward questions!' The mass exodus caused by the outbreak of war in 1914 pushed Henry to the forefront of the school. He was a competent enough sportsman, representing Eton's fledgling rugby team, and was a member of Pop and an editor of the

Eton College Chronicle

. This he endeavoured to liven up with some sensationalism and sports reports mimicking the cheap press, much to the distress of the Colleger working alongside him. Not a classical scholar in the strictest sense, there was never any doubt, given the influence of his house master, that Henry would choose to specialise in history.

As his departure loomed, Henry knew that he would go to war, although at this point it was just about still a choice rather than a compulsion. He refused to let it cast a shadow on his life at Eton and immersed himself in every facet of school life. Mondays were given over to the meetings of the Scientific Society and on Tuesdays the Shakespeare Society met, his favourite. Thursdays were the Essay Society, Fridays were for Pop debates and Saturday perhaps a lecture from a guest. He was amongst those who created their own magazine,

The Jolly Roger

. âOf this a master had to be the censor,' scribbling out the quips that went too far with a blue pencil.

In the summer of 1915 Henry's happy existence at Eton was brought to a premature end as he set out for war, putting on hold a history scholarship at Christ Church. âWell, well, the last letter from the old boy's club,' he wrote at the end of July. âTomorrow I tool up to London, dressed as an Old Etonian. Eton never looked more delightful than she does tonight after a week's continuous downpour ⦠I hope I shall never show myself forgetful of the debt I owe you, darling daddy and mummy for letting me come here ⦠I can say no more [than] thank you, from the very bottom of my heart.'

There was no military affiliation in Henry's immediate family but he specifically wanted a Guards regiment, for the familiarity of Eton friends, and a Scottish affiliation, so that left one choice; the Scots Guards. It was easy to arrange from school. Since the Guards had been mauled at Loos, the average age of their subalterns had dropped dramatically. For the boys filing out of Eton, the Guards proved to be the most popular destination. It lessened the blow of being wrenched from school. Such were their numbers within the regiments that it became almost a continuation of Eton; the same familiar faces, the same social groups day in and day out. But when they finally made it into battle it was going to be a recipe for heartbreak and tragedy.

Henry joined his regiment at Wellington Barracks in September 1915 at the age of 18½. The thought of going to war did not appal him but he was, in his words, ârather less enthusiastic about it than I ought to have been'. He began his training in earnest. He spent the winter, thanks to his aptitude for bombing, doing a short course as an instructor at Southfields near Wimbledon and from there he was able to spend much time not only back at Eton but indulging his passion for Gilbert and Sullivan by trawling London suburbs looking for productions and visiting theatres at Wimbledon, Kennington and Hammersmith. He turned 19 in February and was offered a choice of whether he wanted to go out to France immediately or âwait for warmer weather'. He chose the latter but Henry's reprieve was brief. By Easter he could evade the front no more. It was not until this point, in spring 1916, that he actually underwent any training with the men at Corsham.

There was âlittle buoyancy' about his mood when he realised that he was finally âfor it'. At the end of May Henry departed Waterloo Station with a handful of fellow OEs. The young subalterns on their way to the Guards Division were clueless as to what lay in wait for them. The division, they would discover, was extremely introverted. A young Guards officer fresh out of Eton and newly arrived on the front would have next to no contact with any non-Guardsmen. The Guards were inspired by a powerful

esprit de corps

that would not be diluted by the founding of numerous additional battalions as the war progressed. This would help Henry settle in, but for now, even their own formation was a mystery to him and his companions. Henry knew who was in charge of the division, and who commanded the two Scots Guards battalions, but as for brigadiers or which battalions would be operating near him, the whole thing was a âsealed book'.

At the end of June 1916 the 1st Scots Guards were at Hooge, relieving elements of Canadian units that had been slaughtered in Sanctuary Wood. When the Guards began taking casualties of their own Henry was abruptly summoned to help replace them. Travelling on a night train to Abbeville he cleaned his teeth at Calais, had lunch at Hazebrouck, plodded the last leg to Poperinghe and then âstarted off along what is now probably the most famous road in the world'. Henry found Miles Barne, an older OE in temporary charge of the battalion, and joined B Company fresh out of the line.

When Henry joined his battalion the whole Guards Division had just come back from practising for an attack north of Ypres but the stalemate on the Somme meant that everything elsewhere was shelved. Henry found his first experiences of the trenches rather thrilling; the constant shelling especially left its mark on him. âYou are absolutely helpless, as to go into a dugout is merely to exchange burial alive for disintegration and burial dead.' But the biggest impression left on him was the difference between the reality of life at the front and the âludicrous optimism' of people in England. This optimism was painted on to âour lads in the trenches' by the press. He had seen very little of it himself. The mood was not necessarily depressed, but large swathes of men foresaw no end in sight.

Eton remained, thanks to the presence of so many contemporaries in the immediate vicinity, at the forefront of Henry's mind as the Guards were sent back to rest. As the the Battle of the Somme began, to the north he reported perfect blue skies. It all reminded him of summer at school. âAny water â even a canal â reminds me of the river and any trees â even shell-torn â of Upper Club

2

'. A particular friend, Christopher Barclay, had joined the Coldstream Guards and Henry found plenty of time to pop along and see him. Talking âEton shop' on long walks was their favourite pastime and at the end of the month they even had a party, courtesy of brigade headquarters, complete with a band. When they played the âBoating Song' Henry nearly wept. They danced till midnight, the guns booming away to the south, âflares stabbing the night all around'; and yet the officers of four of the Guard's battalions could forget everything, even the possibility of being summoned to join in the show âand revel as at a children's party'.

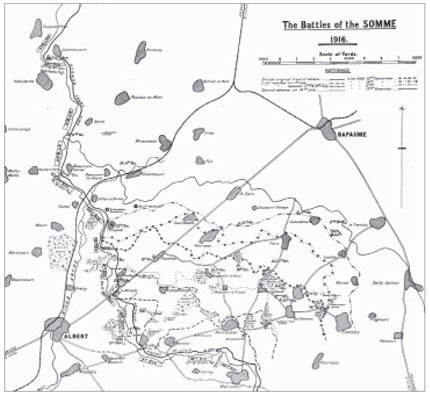

August saw yet more misery for Haig, Rawlinson and the men on the Somme. On 27 July Delville Wood and Longueval were finally secured thanks in part to an obscenely concentrated artillery bombardment. Rawlinson was making negligible progress. Control by seemed to have devolved completely out of his hands, resulting in a series of messy, disjointed attacks directed by his subordinates that were costing Britain dearly. Douglas Haig was determined that this had to stop, but this did not prevent him putting unrealistic expectations on his generals in terms of what he expected them to achieve whilst they pulled back on the obscene wastage of manpower.

By September, seventy-six Old Etonians were already dead on the Somme but the bloodshed was far from over. It had been resolved that High Wood, Ginchy, just to the south-east of Delville Wood, and Guillemont, a little to the south-west of that, would all have to be taken before an all-out offensive could be made on what had originally been the German third line. Since mid August, at Haig's behest, the Fourth Army commander had been planning the attack. Haig was still demanding a decisive breakthrough. He wanted the ridge behind Les Boeufs seized then, as soon as the gap was opened, a mass of cavalry would flood into it. Yet again, as on 1 July, Haig was pressing Rawlinson to take multiple lines in one hit. Guillemont fell at the beginning of the month and Rawlinson ordered a number of attacks on the Ginchy area to prepare for his big push.

The Guards were transferred to Rawlinson's army and began moving on 19 August towards Albert. The train carrying the 1st Scots Guards crawled south. âTo give added piquancy' they were supposed to be on a special tactical train described in Henry's handbooks as being used for rushing troops from one part of the country to another. Their move was not a surprise. Ever since the âbiff' on the Somme had begun the Guards were certain that they would be destined for it at some stage. âThe atmosphere,' Henry wrote, âis rather like that in a music hall when the star turn is just coming on ⦠some fun I should imagine.' Evelyn Fryer, another OE serving with the Grenadier Guards after originally enlisting as a private in the Honourable Artillery Company, was sorely disappointed that thus far the Guards had played no part in the big event to the south. Enthusiasm would be too strong a word but the Guards were honestly pleased to get away from the dreaded Salient.