Blood Brotherhoods (108 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

As he spoke these words, Borsellino knew he was next. He knew that Falcone was his shield against Cosa Nostra. His family often heard him say, ‘It will be him first, then they will kill me.’ When Falcone went to work at the Ministry of Justice in Rome, Borsellino returned from Marsala to Palermo to pick up where his friend left off. Now Borsellino was widely rumoured to be the leading candidate for the job Falcone had designed: ‘Super-prosecutor’, in charge of the National Anti-mafia Directorate, coordinating organised crime investigations at a national level. Borsellino had prepared the maxi-trial with Falcone. Sicily had chosen him, willing or not, to be Falcone’s heir as the symbol of the struggle against Cosa Nostra. He had been informed that the explosive meant for him was already in Palermo.

All of which makes his courage all the more astonishing, and the Italian state’s failure to protect him all the more appalling.

On 19 July 1992, a FIAT 126 stuffed with explosives was detonated outside Paolo Borsellino’s mother’s house in via d’Amelio. The magistrate had just rung the doorbell when he was torn limb from limb.

With Borsellino died his five bodyguards, volunteers all: Agostino Catalano, Vincenzo Li Muli, Walter Eddie Cosina, Claudio Traina, and a twenty-four-year-old female officer from Sardinia called Emanuela Loi. Several times during the previous fifty-six days, Borsellino had gone out alone to buy cigarettes in the hope that he would be shot, thus sparing anyone else from sharing his end.

The via d’Amelio massacre, 19 July 1992. Paolo Borsellino and five police bodyguards were blown apart by a car bomb in Palermo.

At his wife’s insistence, Borsellino’s funeral was private, held in the very church where he had pronounced his own epitaph on 23 June.

The state funeral of his five bodyguards took place in Palermo Cathedral. It turned into a near riot. The streets around were closed off, and a police cordon tried to deny access—for reasons that nobody could understand. Among the vast crowd of grief-stricken citizens shut outside were members of the dead officers’ families. There was screaming, spitting, pushing and shoving. Police fought police, to cries of ‘they won’t let us sit with our dead’. As one eyewitness commented:

The state seemed like a punch-drunk boxer throwing his fists in the wrong direction, at the people. The tens and tens of thousands of Palermitans who had shown up in the piazza to protest against the mafia were being treated as if they were a gigantic public order issue.

Eventually, the cordon broke, and the crowd flooded into the cathedral. The coffins of Borsellino’s bodyguards were greeted with a chorus of ‘

GIUS-TIZ-IA, GIUS-TIZ-IA

.’ Justice. Justice.

T

HE COLLAPSE OF THE OLD ORDER

T

HE SUMMER OF

1992

IN

P

ALERMO WAS A TIME OF RAGE

,

DESPAIR AND DISBELIEF

. It was also a time of enormous cultural and political energy as the healthy part of the city sought to broadcast its feelings. There were demonstrations, torch-lit parades, human chains . . . The tree outside Falcone’s house in via Notarbartolo became a shrine to the heroes’ memory. Balconies across the city were hung with sheets bearing anti-mafia slogans: ‘FALCONE LIVES!’; ‘GET THE MAFIA OUT OF THE STATE’; ‘PALERMO DEMANDS JUSTICE’; ‘ANGER & PAIN—WHEN WILL IT END?’

The echoes from Palermo reverberated across a national political landscape that was in the throes of an earthquake. A many-layered crisis was in the process of utterly discrediting the system that had been in force since 1946. The end of the Cold War was working its delayed effects.

Falcone died on 23 May 1992 in the middle of a power vacuum in Rome. Recent general elections had witnessed a slump in the DC vote. ‘Collapse of the DC wall’, ran one newspaper headline. Following the elections, the beginning of a new five-year parliamentary cycle coincided with the beginning of a new seven-year term for the President of the Republic. A governing coalition had yet to be formed, and newly elected Members of Parliament and the Senate were still busy haggling over who would be the next President of the Republic. Giulio Andreotti was playing a canny game as ever, waiting for other candidates to be eliminated before putting himself forward. The keys to the Quirinale, the Head of State’s palace in Rome, were to be the crowning glory of his long career.

The shame and horror surrounding Falcone’s death made Andreotti’s candidature unthinkable. In the coming months, the most powerful politician in post-war Italy would be increasingly marginalised. Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, a respected Christian Democrat senior statesman with no ‘odour of mafia’ around him, was rapidly elected President.

However, Italy was not allowed to regain its equilibrium after 23 May. On the evening of Borsellino’s assassination, 28 million people followed the news special on the state broadcaster RAI, and a further 12 million watched the horror unfold on the private channels. ‘The mafia declares war on the state’, ran one national headline the next day. The war, in actual fact, had been declared more than a decade earlier. It now looked as if the state was about to

lose

that war. Not only that, but the country itself seemed to be falling apart.

On 16 September 1992, after months of pressure on international currency markets, the lira was forced out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism—the forerunner of the planned single European currency. The debts racked up by the party-ocracy had destroyed Italy’s financial credibility.

The day after the lira’s exit from the ERM, Cosa Nostra killed another key component of what had once been the DC machine in Sicily: Ignazio Salvo, the tax collector brought down by the maxi-trial, was shot dead at the door of his villa. Like Salvo Lima, Ignazio Salvo paid the price for failing to protect Cosa Nostra from Falcone and Borsellino.

Meanwhile, a huge corruption scandal had begun, with investigations into the Socialist Party in Milan. The summer and autumn months witnessed more and more politicians and party functionaries targeted by investigations grouped under the name ‘Operation Clean Hands’. The scandal continued to gain momentum until it engulfed the weakened ‘party-ocracy’. By the end of 1993, some two hundred Members of Parliament were under investigation. In January 1994, the Christian Democrat Party was formally dissolved. The First Republic, as it is now known, was dead. Cosa Nostra had helped finish it off.

Yet precisely because the old regime was toppling, Italy found the will to respond to public dismay and fight back. By murdering Falcone and Borsellino, Shorty Riina and his entourage brought down the state’s retribution not just on themselves, but on the whole Italian underworld. For a brief and extraordinary season, between Borsellino’s death in July 1992 and the spring of 1994, Italy’s institutions finally called the mafias to account for more than

a decade of slaughter. Even crude numbers registered the transformation. Between 1992 and 1994, 5,343 people were arrested under the Rognoni–La Torre anti-mafia law. In 1991 there were 679 mafia-related homicides in Italy; by 1994 the figure had fallen to 202.

Immediately after Borsellino’s murder, 7,000 troops were sent to Sicily to relieve the police of more mundane duties. New anti-mafia legislation was rushed through parliament—legislation that arrived more than a century late, but which was welcome nonetheless. A witness-protection programme was set up. Just as importantly, a tough new prison regime was imposed on underworld bosses. At long last, Italy had the means to stop jails like the Ucciardone becoming command centres for organised crime.

The fight against the mafia was also stepped up on the international front. In September 1992, the Cuntrera-Caruana clan, key members of the heroin-dealing Transatlantic Syndicate, suffered a serious blow: three Cuntrera brothers, Pasquale, Paolo and Gaspare, were extradited from Venezuela.

A new Chief Prosecutor from Turin, Gian Carlo Caselli, volunteered to enter the Palermo war zone. Caselli’s bravery and absolute professional integrity were not the only things that made him the perfect man for the job. He had a highly distinguished record investigating the Red Brigades in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He had experience of handling penitents, and of the rigours of life under armed escort. He had also supported Falcone at every stage of his battles with the High Council of the Magistracy. Palermo prosecutors were galvanised as never before.

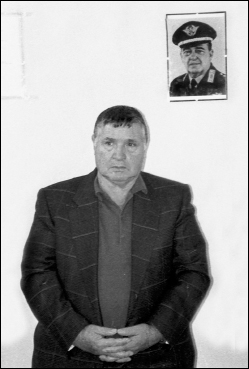

After his capture in 1993, Riina is made to pose before a picture of one of his most illustrious victims, General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa.

In January 1993, the very day of Caselli’s arrival in Sicily, Shorty Riina was captured as he and his driver circled a roundabout on the Palermo ring road. He had been on the run since 1970. But as with all the many fugitives from justice in Cosa Nostra, ‘on the run’ was an entirely inappropriate metaphor. In all his twenty-three years of evading capture, Riina had not only masterminded his coup d’état within Cosa Nostra, managed his economic empire and murdered countless heroic representatives of the law, he had also

married in church, fathered and schooled four children, and obtained the best medical care money could buy.

Riina’s arrest resulted from inside information from his former driver. Since Borsellino’s death, magistrates had been offered a flood of such tip-offs. The number of penitents grew exponentially too. Some were encouraged by the new measures to protect them; others were afraid of the new prison regime; and some were just shocked to their human core by what happened to Falcone and Borsellino. Gaspare ‘Mr Champagne’ Mutolo, the Ferrari-driving heroin broker, turned state’s evidence in May 1992 after months of gentle encouragement by Giovanni Falcone. He was the last man to be interrogated by Borsellino. The via d’Amelio bomb removed the residues of Mutolo’s reticence, and from then on he held nothing back. Having been in prison with bosses close to Riina until the spring of 1992, he was able to supply the first insider account of Cosa Nostra’s strategy following the Supreme Court’s ruling on the maxi-trial. He also provided evidence that led to the arrest, on Christmas Eve 1992, of Bruno Contrada, former chief of police of Palermo and Deputy Head of Italy’s internal intelligence service. Contrada would ultimately be convicted of collusion with Cosa Nostra.