Blood Brotherhoods (69 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the mafia rebuilt Palermo in its own gruesome image in a frenzied wave of building speculation that became known as the ‘sack of Palermo’. There were two particularly notorious mafia-backed politicians who were key agents of the sack. The first was Salvo Lima, a tight-lipped, soft-featured young man whose only affectation was to smoke through a miniature cigarette holder. He looked like the middle-class boy he was—the son of a municipal archivist. Except that his father was also a mafia killer in the 1930s. (That little detail of Lima’s background had been buried, along with all the other important information from the Fascist campaigns against the mafia.) In 1956, Lima came from nowhere to win a

seat on the city council, a post as director of the Office of Public Works, and the title of deputy mayor. Two years later, when Lima became mayor, he was succeeded at the strategic Office of Public Works by the second key

mafioso

politician, Vito Ciancimino. Ciancimino was brash, a barber’s son from Corleone whose cigarette habit had given him a rasping voice to match his abrasive personality. In the course of their uneasy alliance, Lima and Ciancimino would wreak havoc in Palermo, and reap vast wealth and immense power in the process.

Men like Lima and Ciancimino were known as ‘Young Turks’—representatives of a thrusting new breed of DC machine politician which, across Sicily and the South, was beginning to elbow the old grandees aside. In the 1950s, the range of jobs and favours that were available to patronage politicians began to increase dramatically. The state grew bigger. Government enlarged its already sizeable presence in banking and credit, for example. Meanwhile, local councils set up their own agencies to handle such services as rubbish disposal and public transport. Sicily’s new regional government invented its own series of quangos. As the economy grew, and with it the ambitions for state economic intervention, more new bureaucracies were added. In 1950, faced with the scandal of southern Italy’s poverty and backwardness, the DC government set up the ‘Fund for the South’ to sluice large sums into land reclamation, transport infrastructure and the like. Money from the Fund for the South helped win the DC many supporters, and put food on many southern tables. But its efforts to promote what it was hoped would be a dynamic new class of entrepreneurs and professionals were a dismal failure. As things turned out, the only really dynamic class in the South was the DC’s own Young Turks. The Fund for the South would turn into a gigantic source of what one commentator called ‘state parasitism and organised waste’. Government ‘investment’ in the South became, in reality, the centrepiece of a geared-up patronage system. Young Turks began to inveigle their way into new and old posts in local government and national ministries. Journalists of the day dubbed the Christian Democrat party ‘the white whale’ (i.e., Moby Dick) because it was white (i.e., Catholic), vast, slow, and consumed everything in its path.

In Palermo, for all these new sources of patronage, it was the simple business of controlling planning permission that gave Young Turks like Lima and Ciancimino and their mafia friends such a large stake in the building boom.

The sack of Palermo was at its most swift and brutal in the Piana dei Colli, the flat strip of land that extends northwards between the mountains from the edge of Palermo. It has always been a ‘zone of high mafia density’, in the jargon of Italian mafiologists. Indeed, it has as good a claim as anywhere to being the very cradle of the mafia: its beautiful lemon groves

were where the earliest

mafiosi

developed their protection racket methods; the Piana dei Colli was the theatre for the ‘double vendetta’ intrigues of the 1870s that had been investigated by Ermanno Sangiorgi. A century on from those beginnings, the mafia smothered its birthplace in a concrete shroud. The scale of the ruin was immense. The gorgeous landscape of the Conca d’Oro, which for Goethe had offered ‘an inexhaustible wealth of vistas’, was transformed into an undifferentiated swathe of shoddily built apartment blocks without pavements or proper amenities.

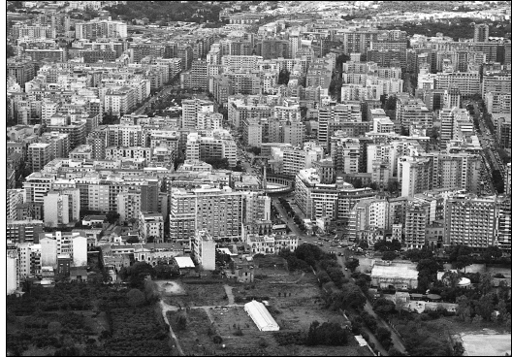

The sack of Palermo. From the late 1950s, the construction industry propelled organised crime in Sicily and Calabria to new levels of wealth and power.

In 1971, when the sack of Palermo was complete, a journalist climbed Monte Pellegrino, the vast rocky outcrop that surges between the Piana dei Colli and the sea. The view below him had once been stunning. Now it was shocking.

From up there you can cast your eyes across the whole city and the Conca d’Oro. Palermo seems much bigger than you would imagine: long rows of houses spreading out from the periphery towards the orange groves. Concrete has now devastated one of the most beautiful natural spectacles in the world. The huge blocks of flats, all alike, seem to have been made by the same hand. And that hand belongs to ‘don’ Ciccio Vassallo. More than a quarter of the new Palermo is his work.

Francesco Vassallo, known as ‘don Ciccio’ (‘don Frankie’), or ‘King Concrete’, was by a distance the dominant figure in the Palermo construction industry in the 1960s. Between 1959 and 1963, under the Young Turks Salvo Lima and Vito Ciancimino, Palermo City Council granted 80 per cent of 4,205 building permits to just five men, all of whom turned out to be dummies. One of the five subsequently got a job as a janitor in the apartment block he had nominally been responsible for building. Behind those five names, more often than not, stood don Ciccio Vassallo.

King Concrete was a fat, bald, jowly man with a long nose, dark patches under his eyes, and a preference for tent-like suits and loud ties. He rose from very humble origins in Tommaso Natale, a

borgata

or satellite village that sits at the northern end of the Piana dei Colli. Reputed to be only semi-literate, he was the fourth of ten children born to a cart driver. Police reports mention Vassallo as moving in mafia circles from a young age; his early criminal record included proceedings for theft, violence and fraud—most of them ended in a suspended sentence, amnesty or acquittal for lack of proof. His place in the local mafia’s circle of influence was cemented in 1937 by marriage to the daughter of a landowner and

mafioso

, Giuseppe Messina. With the Messina family’s muscle behind it, his firm established a monopoly over the distribution of meat and milk in the area around Tommaso Natale. Vassallo and the Messinas were also active in the black market during the war. When peace came, Vassallo started a horse-drawn transportation company to ferry building materials between local sites. His mafia kinfolk would be sleeping partners in this enterprise, as in the many lucrative real-estate ventures that would come later.

Suddenly, in 1952, Vassallo’s business took off. From nowhere, he made a successful bid to build a drainage system in Tommaso Natale and neighbouring Sferracavallo. He had no record in construction; it was not even until two years later that he was admitted onto the city council’s list of approved contractors. He was only allowed to submit a tender for the contract because of a reference letter from the managing director of the private company that ran Palermo’s buses. The company director would later become Vassallo’s partner in some lucrative real-estate ventures. At the same time, Vassallo received a generous credit line from the Bank of Sicily. Then his competitors withdrew from the tendering process for the drainage contract in mysterious circumstances. Vassallo was left to thrash out the terms of the deal in one-to-one negotiations with the mayor, who would also later become his partner in some lucrative real-estate ventures.

In the mid-1950s, King Concrete started to work closely with the Young Turks. Construction was becoming more and more important to the economy of a city whose productive base, such as it was, could not compete

with the burgeoning factories of the ‘industrial triangle’ (the northern cities of Milan, Turin and Genoa). By the 1960s, 33 per cent of Palermo workers were directly or indirectly employed in construction, compared to a mere 10 per cent in Milan, the nation’s economic capital. However temporary the dangerous and badly paid work in Palermo’s many building sites might be, there were few alternatives for ordinary working-class

palermitani

. Which made construction workers a formidable stock of votes that the Concrete King could use to attract political friends. Friends like Giovanni Gioia, the leader of Palermo’s Young Turks, who would go on to benefit from a number of lucrative real-estate ventures piloted by Vassallo.

The notion of a ‘conflict of interests’ was all but meaningless in building-boom Palermo. The city municipality’s director of works became King Concrete’s chief project planner. From his political contacts, the rapidly rising Vassallo acquired the power to systematically ignore planning restrictions. The Young Turk, Salvo Lima, was repeatedly (and unsuccessfully) indicted for breaking planning law on Vassallo’s behalf. During the sack of Palermo, journalists speculated ironically about the existence of a company they called VA.LI.GIO (VAssallo—LIma—GIOia). They were successfully sued. Rather pedantically, the judges ruled that no such legally constituted company existed.

In the mid-1960s, the market for private apartments reached saturation point. By that stage King Concrete had built whole dense neighbourhoods of condominia that were without schools, community centres and parks. Ingeniously, he then turned to renting unsold apartments and other buildings for use as schools. In 1969 alone he received rent of nearly $700,000 (in 1969 values) from local authorities for six middle schools, two senior schools, six technical colleges and the school inspectorate. The DC press hailed him as a heroic benefactor. In the same year he was recorded as being the richest man in Palermo.

It pays to remember that don Ciccio Vassallo was an

affarista

rather than an entrepreneur. His competitive advantage lay not in shrewd planning and investment, but in corruption, in making useful friends, and of course in the unspoken menace that shadowed his every move. Right on cue, unidentified ‘vandals’ would cut down all the trees on any stretch of land that had been zone-marked as a park. Any honest company that somehow managed to win a contract from under the mafia’s nose would find its machinery in flames. Dynamite proved a handy way of accelerating demolition orders.

In 1957, just as the sack of Palermo was about to enter its most devastating phase, a mafia power struggle began in King Concrete’s home village of Tommaso Natale. His own family was soon drawn in. In July 1961 his brother-in-law, Salvatore Messina, was shotgunned to death by an assassin

who had sat in wait for him for hours in the branches of an olive tree. Another brother-in-law, Pietro, was shot dead a year later. A third brother-in-law, Nino, only saved himself from the same fate by hurling a milk churn at his attacker when he was ambushed; it is thought he then left Sicily. The fact that don Ciccio himself was not attacked (as far as we know) shows that his power now transcended any local base: he was a money-making machine for the entire political and mafia elite.

Mass migration was one of the most important characteristics of Italy’s economic miracle. As the industrial cities of the North boomed, they sucked in migrants. About a million people moved from the South to other regions in just five years, between 1958 and 1963.

Mafiosi

also became more mobile in the post-war decades: their trade took them to other regions of Italy. In some places, gangsters went on to found permanent colonies. Those bases in central and northern Italy, as well as in parts of the South not traditionally contaminated by criminal organisations, are one of the distinctive features of the recent era of mafia history. Nothing similar is recorded in previous decades.

Some of the American hoodlums who were expelled from the United States after the Second World War were the first to set up business outside the mafia heartlands of Sicily, Calabria and Campania. Frank ‘Three Fingers’ Coppola dealt in drugs from a base near Rome, for example.

The earliest signs of mafia colonisation from

within

Italy came in the great North–South migration during the economic miracle. In the mid-1950s, Giacomo Zagari founded one of the first cells of

’ndranghetisti

near Varese, close by Italy’s border with Switzerland. The murder of a foreman in the early hours of New Year’s Day in 1956 revealed the existence of mafia control among the Calabrian flower-pickers of the Ligurian coast near the French border.