Blood River (32 page)

Authors: Tim Butcher

Clement explained the racist character of colonial Stanleyville,

where black Congolese had to apply for written permission even

to walk the streets of the city centre, and how the rumblings of a

national independence movement first stirred here. Patrice

Lumumba, the Congo's post-independence Prime Minister who

was later assassinated on the orders of America and Belgium, was

based in Stanleyville in the 1950s, working as a post-office

official, when he first began organising a national, Congolese

political party calling for an end to Belgian rule. Again, there

were killings here, this time by Belgian security forces cracking

down on Lumumba's nascent Congolese National Movement

(MNC), an event commemorated by the large Martyrs' Square in

the city centre just next to the ruin of the main post office where

Lumumba worked.

The square has seen plenty of martyring since independence.

After his assassination in 1961, Lumumba's supporters set up

their own parallel government here, and there were bloody

skirmishes in the square between them and troops loyal to the

capital, Kinshasa. Rebel groups came and went, white mercenaries stormed the city centre, and foreign armies invaded.

Clement's account of it was hazy, but I could not criticise him for

this. In a nation with little institutional memory, it would be

wrong to blame him for not keeping track of this city's history.

The numerous rebellions, uprisings, mercenary raids and

invasions blurred into one grim, bloody continuum.

A few days later I dragged Clement to the city's main post office

in search of any evidence of Lumumba. The country's postal

system had not worked for decades and the same 1950s building

where Lumumba had worked was a terrible mess. Windows were

smashed, the sorting hall sorted nothing today but dust and

cobwebs. Entire corridors and rooms had been surrendered to the ravages of tropical damp. But when I asked an old man hanging

around the main entrance about Lumumba, there was a flicker of

recognition. I was shown a dirty old office and told this was

where he had worked. It was empty apart from a desk with an old

Bakelite phone connected to a line that had not functioned in

living memory. And when I asked if there were any other artefacts

from Lumumba's time, I was shown the cover of a quarterly

postal-union magazine entitled The Postal Echo. The innards had

long gone, but on the cover was printed `Managing Editor: Patrice

Lumumba'.

From this now-ruined building Lumumba had dreamed of

independence for the Congo and the end of eighty years of

colonial tutelage that began after Stanley's expedition passed

down the nearby Congo River. And it was outside this building

that Lumumba's dream died, in round after round of bloodletting

in Martyrs' Square.

Only a handful of foreigners remain in Kisangani today, from a

population that once numbered more than 5,000. During my stay

I saw plenty of outsiders, but they were almost all aid workers or

UN people, working on short-term contracts, whose experience

went back just a few months or years. Many were hard-working,

deeply committed to helping the local people, but pretty much all

of those I spoke to found the scale of the humanitarian problems

simply overwhelming. I heard heartbreaking stories about corrupt

Congolese officials pocketing aid money intended for local

public-health workers, and local soldiers not just looting aid

equipment, but brazenly asking for cash to hand it back to its

rightful owners. Many in the aid community spent their time

counting the days until their contracts were up and they could go

back to the real world.

Yani Giatros's attitude to Kisangani was very different. He was

born in the Congo in 1947, part of a once-huge Greek expat community who had set themselves up as traders, mechanics and farmers during the Belgian colonial period. So large was the

Greek community in Kisangani that the city boasted a Hellenic

Social Club with restaurant, bar and sports facilities. By the time

I got there, the club was barely functioning, but its lunchtime

moussaka buffet was one of the few palatable meals available in

the entire city.

'Where logic ends, the Congo begins,' Yani said as he bent his

face down to spoon up some moussaka. He peered at me over his

spectacles as I made my notes.

'I was born here in the Congo. When my parents took me as a

child back to Greece, it was more primitive than here. I used to

look forward to coming back to the Congo because it was more

advanced than Greece. Can you imagine that?

`This city alone used to have a regular flight by a plane spraying

for mosquitoes. Every day trucks would drive around the city

sprinkling water on the roads to stop the dust rising. You could

pick from six cinemas. Eros was my favourite. The whole city

centre was electrified. Right at the end of the colonial period, in

the 1950s, they put in a hydroelectric power station on the

Tshopo with four generators, which was enough for the whole

city.

`But even if you accept the fighting, the wars and the struggle

for control, what do you have today? Nobody with any interest in

making this place work, apart from a few aid workers.'

Yani raised his eyes and a club waiter came running with a

bottle of Primus. He lit a cigarette and drew heavily on it before

leaning forward conspiratorially.

`You see him?' he asked quietly, flicking his eyes in the

direction of a photograph of the country's president, Joseph

Kabila, catapulted into the job in his twenties after his father,

Laurent Kabila, was assassinated.

`What skills does he have to run a country like this, or even a

place like Kisangani? In all his life he has never been here, and

this is the second city of the country he is president of. It is ridiculous. Christ, before his father took over this country, the

young Kabila was driving taxis for tourists in Tanzania, and now

he is meant to be a national leader!' His harrumph of scorn was so

loud it made the waiter jump.

`Who is there who actually wants this place to work? I don't see

anybody. Let me give you an example. An aid group went to the

Tshopo power station in the last couple of years. They found

three of the four generators were broken, so they raised the money

and shipped replacements to Matadi, the country's main port

down near where the Congo River reaches the Atlantic. And they

flew in engineers to Kisangani ready to fit everything.

`So what happened? The customs, the officials, the people

down at Matadi blocked the generators from coming in. The

foreign engineers got more and more frustrated until they eventually left, God knows where the new generators ended up, and the

lights still go out here in Kisangani.'

He leaned forward again, fixed my gaze and whispered.

`The Congo was built with the chicotte, and the only way to

rebuild it will be with the chicotte.' He was referring to a whip

made from dried hippopotamus hide, which the early Belgian

colonialists used savagely when dealing with their subjects in the

Congo. Even today, almost fifty years after the Belgians left, the

chicotte endures as a sinister symbol of their brutality.

After two weeks of delay in Kisangani, I finally got the news I had

been praying for. A Congolese boat, under charter to the United

Nations, was heading downriver to Mbandaka, more than 1,000

kilometres downstream. The journey could take a week, maybe

longer. I did not care. I was on the move again.

To secure a place on the boat I needed the assistance of Robert

Powell, the UN's transport boss for Kisangani and a former soldier

in the British Army. He helped me through the final stretch of the

bureaucratic paperchase needed to travel on the UN boat, before

giving me the most unexpected experience of my fortnight in Kisangani. Robert is a plain-speaking Yorkshireman and an

advocate of the British Army adage 'any fool can be uncomfortable'. In the remote city where I had lived in an austere priest's

cell on a diet of fruit and cassava bread, Robert made sure he was

true to his word.

The house he occupied had been turned into a palace by local

standards. He had a generator, a fridge full of freshly imported

meat, South African satellite television, air-conditioning and no

end of other luxuries. I spent my last night in Kisangani enjoying

his ribald company and ploughing through a mountain of sausage

and `bubble and squeak', prepared, as my host boasted, `like my

mum taught me back home'.

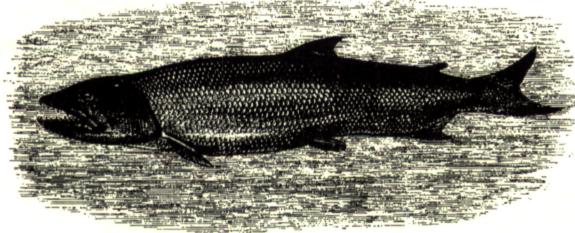

After dinner we found a shared interest to talk about: fishing.

In South Africa fishermen get excited if they catch a two-kilo

Tigerfish. Robert explained how everything was so much bigger

on the Congo River where a separate species, the Goliath

Tigerfish, reaches upwards of fifty kilos. I was sceptical until he

showed me pictures of specimens that had been caught in the nets

of local fishermen. They were as big as children, with uglylooking teeth and sinister eyes. We spent the rest of the evening

plotting how to take one of these leviathans on rod and line, idly

dreaming about running fishing safaris out of Kisangani for multimillionaire anglers.

After my night of Yorkshire hospitality there was just one more

thing I needed to do in Kisangani. I wanted to say goodbye to

Oggi. We met in the bar of the Palm Beach Hotel. When I

explained that I had got a place on a boat heading downstream, he

smiled half-heartedly. He seemed a bit distracted as if he had

something important to say to me, but could not quite come out

with it.

As the Primus flowed, Oggi became more and more nostalgic.

He told me stories of how hardy tourists arrived here in the 1980s,

coming through the jungle on overland Africa tourist trucks all the way from Europe, and how he took them out for day trips on

the river. It reminded me of an elegant film poster I had once seen

advertising a French movie about a pan-African journey in the

1950s. The poster showed the continent in outline with a thick

red line snaking down from Tangier, Africa's closest point to

Spain, across the desert sands and then through the equatorial

jungle before eventually reaching Cape Town at the southern heel

of the continent. A few place names were marked on the poster,

and I clearly remember that Stanleyville was one of them, just

another waypoint on a road that once traversed the entire

continent.

'Those trucks stopped coming in the late eighties,' Oggi said.

`The forest ate those roads, and the problems with corrupt

officials meant our city was slowly written off the map.'

Oggi's fluent English was entirely self-taught. He was tough -

he had lost count of the malaria episodes he had survived. And

he was resourceful - somehow he fed his family and kept them

clothed without any meaningful income. But just like Georges,

Benoit and many other Congolese I had met, all his energies,

skills and talents were spent on the daily struggle to survive.

The failure of the Congo is so complete that its silent majority -

tens of millions of people with no connections to the gangster

government or the corrupt state machinery - are trapped in a

fight to stay where they are and not become worse off. Thoughts

of development, advancement or improvement are irrelevant

when the fabric of your country is slipping backwards around

you.

After enough Primus to make his eyes rheumy, Oggi found the

inner strength he had been looking for. He put his hand on my

forearm, leaned forward and made the most wretched of pleas.

`Please, Mr Tim, I have a huge favour to ask. My son, my fouryear-old, has no future here. There is nothing for him in

Kisangani. I know which way this city is going. Please will you

take him with you to South Africa and give him a new life.'

There was no way I could smuggle a child onto the UN boat

with me. I felt wretched having to turn Oggi down. But I felt more

wretched that he had to resort to asking me, someone he had

known for only a few days, to save his child from the Congo.

River Passage

FIKE, STANLEY FALLS.