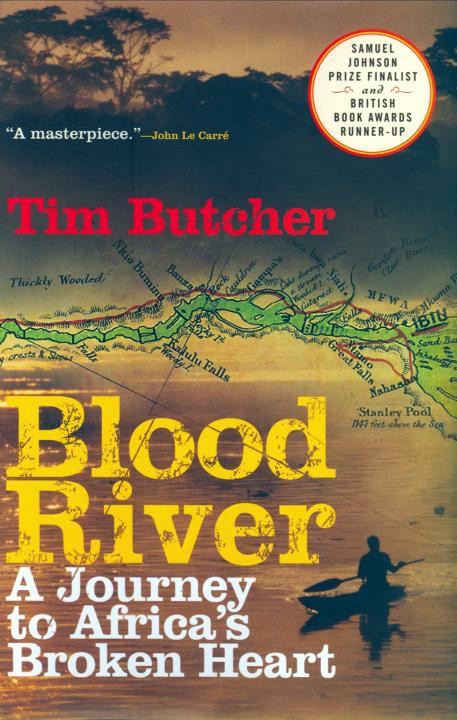

Blood River

Authors: Tim Butcher

Cobalt Town

Advertisements from The Guide to South and East Africa (for the Use of

Tourists, Sportsmen, Invalids and Settlers), 1915

The airline that was to fly me to the Democratic Republic of

Congo in August 2004 was as rickety as the country's latest peace

deal. Hewa Bora had been cobbled together from the remnants of

various bankrupt versions of the national carrier - Congo Airlines

and Zaire Airlines - and although the flight I was waiting for was

a scheduled one from Johannesburg to Lubumbashi, the Congo's

second city and capital of the south-eastern province of Katanga,

there was something about the behaviour of the ground crew and

my fellow passengers that suggested it was anything but routine.

A middle-aged Congolese man, hoping to make it to

Lubumbashi, spotted my concern as I winced at the check-in

muddle. He tried to reassure me. 'I have family here in South

Africa, but whenever I travel with Hewa Bora I never know for

sure if the plane will take off, or even if there is a plane. It really

is a Maybe Airline - Maybe You Get There, Maybe You Don't.'

I waited patiently, watching the ebb and flow of the passengers'

mood. One minute they seemed happy, as a female member of

staff in Hewa Bora uniform - an elegant blue cotton wrap spotted

with yellow teardrops - checked the name of the person at the

front of the queue against the manifest. But then the same member

of staff would get up from her chair and disappear from view,

prompting groans of frustration from the crowd. The flight was

not full, but my fellow passengers all seemed to be carrying

unfeasibly large amounts of luggage, mostly electrical goods like

televisions and CD players, wrapped in the woven-plastic,

tricolour bags of red, white and blue that you see all over the

developing world.

Against this bulky display, my own luggage seemed rather

meagre. I had a green rucksack packed with clothing, bedding and a mosquito net, and two shoulder bags for my notebooks, camera,

laptop computer and satellite telephone. I wanted to keep it as

light as possible so that it could be carried on foot if need be, so

the only book I brought with me was Stanley's account of his

journey, Through the Dark Continent. I had read it several times,

but if my journey was successful I wanted to be able to make a

direct comparison between what he found in the late nineteenth

century and what I found in the early twenty-first.

My first problem was how to reach the spot where Stanley

arrived in the Congo in September 1876. He had been following

the established route of Arab slavers across what is now the east

African country of Tanzania, before crossing Lake Tanganyika by

boat and arriving in the Congo at the village of Mtowa on the

lake's western shore. Under the Arabs, Mtowa developed into a

large centre for the trans-shipment of slaves and ivory. Its name is

not to be found on modern maps of the Congo, but I had been able

to establish that it lies about thirty kilometres north of Kalemie, a

once-prosperous port set up by the Belgians on the lake. Fifty

years ago it was possible to reach Kalemie by rail, road and ferry,

but today its only regular connection with the outside world is a

weekly shuttle flight arranged by the United Nations peacekeeping mission, MONUC, to serve Kalemie's small garrison of

peacekeepers. The shuttle flight leaves from Lubumbashi, capital

of the Congo's Katanga province, and a UN administrator had

promised that if I made it to Lubumbashi, I could take my place

on a waiting list for the trip to Kalemie.

The chaos at the check-in desk in Johannesburg took hours to

sort out, but I was in the wonderful position of being under no

time pressure. Whenever my journalism has taken me overseas,

time has always been of crucial importance, a situation made

worse by twitchy foreign editors, deadlines and competitive

colleagues. But this time I faced no such constraints. For my

attempt to cross the Congo I was entirely on my own. It was

pleasantly liberating and as time passed at the airport I was happy to people-watch, trying to guess the nationality of the one other

white person on the flight, or why an Asian lady was travelling

solo to the Congo.

Johannesburg International Airport is one of the great hubs of

modern African travel, a first-world airport offering flights to

some of the rougher third-world destinations. As I headed to the

gate for the Lubumbashi flight, I looked at the well-stocked

boutiques and felt the downwash from the powerful airconditioning, and wondered when I would next experience the

same.

The Hewa Bora cabin crew had laid out copies of a Kinshasa

newspaper, L'Avenir, on the seats in business class and I snaffled

one as I shoulder-barged my way to my economy seat. It was more

of a samizdat newsletter than a newspaper, comprising four pages

amateurishly printed on a single folded sheet of very cheap,

coarse paper. The ink came off on my fingers and there were no

decipherable photographs. But I could decipher the paper's tone,

a tone that was rabidly anti-Rwandan. There were various articles

claiming that the paper had seen documentary evidence proving

Rwanda was about to attack the Congo and there were vicious

denunciations of various pro-Rwandan Congolese rebels, such as

my old contact, Adolphe Onusumba. Under the terms of the 2002

peace deal that was meant to have ended the Congo's war, all the

major rebel groups, including the pro-Rwandan ones, had taken

their place in a transitional, power-sharing government in

Kinshasa. The arrangement was fragile and, as I could see from

the deeply xenophobic tone of L'Avenir, the fault line separating

Rwandans from Congolese remained explosive.

Since the 1994 genocide, Rwanda has been regarded by many

outsiders as a tiny, frail country bullied by its larger neighbours.

This is a grossly inaccurate generalisation. With a government

now dominated by Tutsis, Rwanda punches way above its weight

in regional affairs. There are clear parallels with Israel, another

small country of people driven by the memory of mass murder committed against them to dominate its neighbours militarily,

and the neighbour that Rwanda bosses most is the Democratic

Republic of Congo. On a map, tiny Rwanda is overshadowed by

the vastness of the DRC, but for the past ten years it has been

Rwanda that has loomed over the DRC. In 1996 Rwanda's Tutsidominated forces invaded the country and orchestrated the

ousting of Mobutu the following year, and in 1998 the same forces

turned on Laurent Kabila, the man they had installed as Mobutu's

replacement, starting the conflict that has so far cost four million

lives.

For many Congolese, the Tutsis who now rule Rwanda play the

role of bogeymen. Tutsis are taller and thinner than their ethnic

neighbours, with finer features, and I heard many Congolese

cursing them for 'not looking like us'. There were plenty of less

polite insults. The Tutsi/non-Tutsi divide is one of central

Africa's great social divisions and it was to have enormous impact

on my attempt to cross the Congo.

Eight weeks before I flew to Lubumbashi, an ethnic Tutsi

Congolese warlord broke the terms of the 2002 peace treaty when

he mobilised a force and launched an attack on the Congolese

town of Bukavu that sits on the border between DRC and Rwanda.

His motives were unclear, but the result fitted into the depressing

pattern of central African turmoil. After thirty-six hours of

savagery, scores of people lay dead, thousands had fled their

homes and the entire eastern sector of the country was pushed to

a state close to war. The Congolese authorities were quick to

blame the Tutsi-led regime across the border in Rwanda, accusing

them of arming and protecting the rebels. The accusations were

soon followed by retaliatory attacks from Congolese troops on

groups linked to Rwanda's Tutsis. I knew that the relationship

between the DRC and Rwanda was tense, but the racist bile I

read in L'Avenir revealed the depth of enmity between the two

sides. All I could do as the plane made the three-hour crossing

from South Africa over Zimbabwe and Zambia en route to Lubumbashi was pray that some sort of calm would he reestablished before I reached eastern Congo.

If you look at a map of the Congo, you see that the country appears

to have grown a vestigial tail around its bottom right-hand corner,

known as the Katanga Panhandle. On the surface there seems no

clear reason for this outcrop of Congolese territory surrounded on

three sides by its southern neighbour, Zambia. It is below the soil

that you find the reason why the early Belgian colonialists in the

late nineteenth century staked the territory so obstinately, in

defiance of British pioneers probing northwards from what was

then Rhodesia. The panhandle includes some of the richest

deposits of copper, cobalt and uranium on the planet, a geological

quirk that the early Belgian colonialists identified more smartly

than their British counterparts.

While Congo's other provinces have large diamond and gold

deposits, it was mainly on Katanga's mineral wealth that the

Belgian colony grew rich in the mid-twentieth century. The

uranium for the atom bombs dropped by America on Hiroshima

and Nagasaki came from a mine in Katanga, and it was Katanga's

vast copper deposits that really powered the colony's growth

when the reconstruction of Europe and Japan after the Second

World War drove a surge in demand for copper. Most of the

mineral profits from Katanga were taken by the Belgians, repatriated to Brussels and divided among shareholders from various

private corporations, or Societes, created by the colonial authorities. But some of the profits were reinvested in Katanga, to build

a number of mines, processing plants and factories, serviced by

new towns built out of the virgin bush and connected by a web of

roads and railways. By the mid-twentieth century Katanga was the

most developed province in all of the Congo.

The blessing of Katanga's mineral wealth became its curse

when Belgium granted independence to the Congo on 30 June

1960. While maintaining the illusion of handing over a single country to the black Congolese, the authorities in Brussels secretly

backed the secession of Katanga from the Congo, financing,

arming and protecting the pro-Belgian Katangan leader, Moise

Tshombe, in return for a promise that the Belgian mining interests

in Katanga would be protected. It was one of the most blatant acts

of foreign manipulation in Africa's chaotic independence period,

and it culminated in one of the cruellest acts of twentieth-century

political assassination, when Patrice Lumumba, the first

Congolese national figure to win an election, was handed over by

Belgian stooges to be murdered by Tshombe's regime.

Lumumba's mistake was to hint at pro-Soviet sympathies. The

mere possibility of the Congo, with its huge deposits of copper,

uranium and diamonds, falling into the Soviet sphere of

influence during the Cold War was too much for the Western

powers. Several African nations were already moving into the

Communist camp but the Congo was, in the eyes of the West,

simply too important to lose so Brussels, with the connivance of

Washington, engineered Lumumba's arrest, torture and transfer

to the capital of Katanga, then known by its Belgian name of

Elisabethville, today's Lubumbashi.