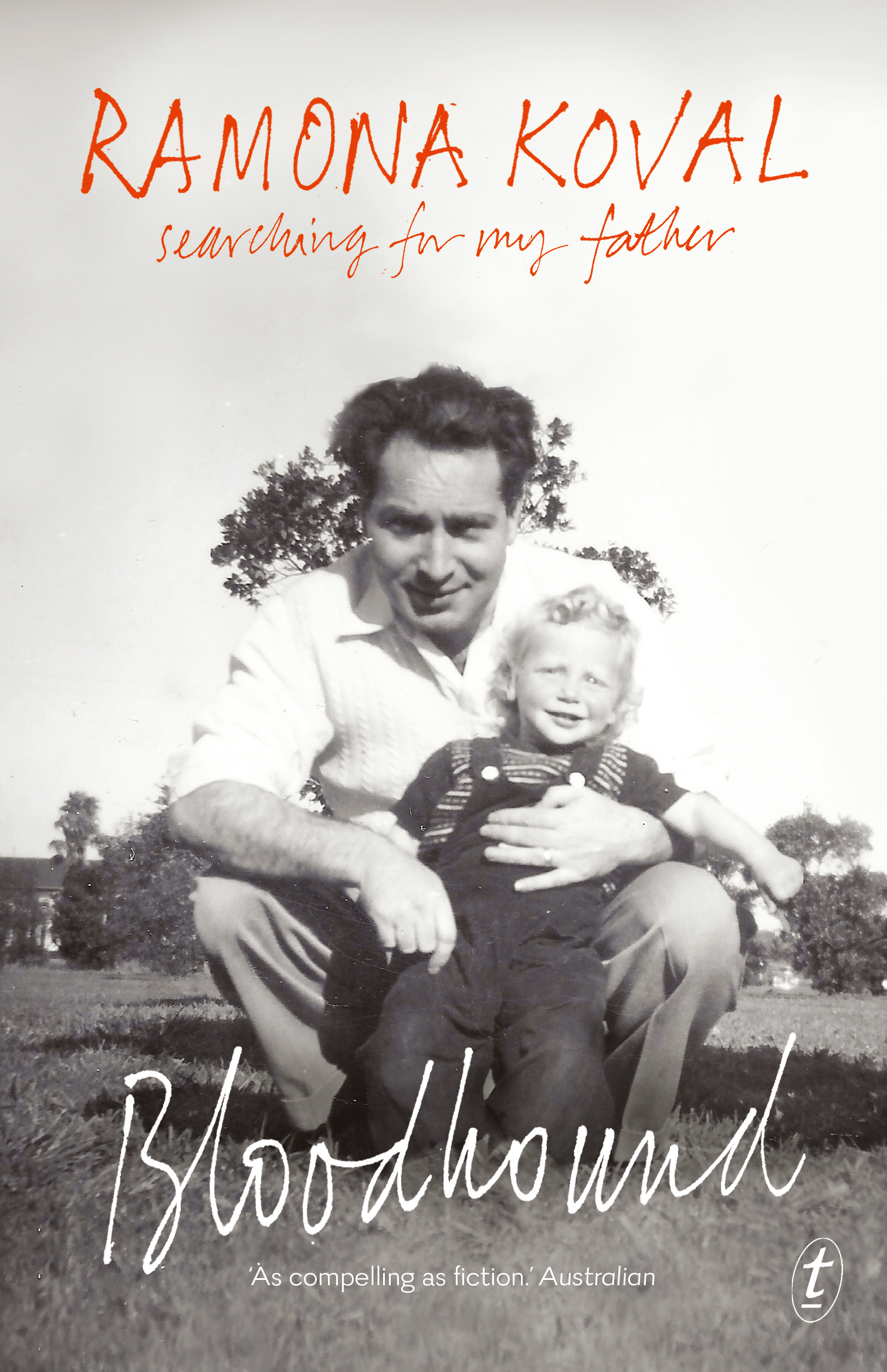

Bloodhound

Authors: Ramona Koval

PRAISE FOR RAMONA KOVAL

âI thought I had read every “take” on the Holocaust, but Ramona Koval adds something fresh with

Bloodhound

: the drive to find a more appealing lineage; a rebuilding after the disaster.'

Australian Book Review

âKoval's painstaking collection of evidence and tracing of clues is as compelling as fictionâ¦In

Bloodhound

, Koval is hunter and prey to truths that taunt and console.'

Australian

âAccompanying Koval as she turns up at strange houses with flowers to solicit photographs, recollections and cell samples in picaresque fashion is made great fun⦠[

Bloodhound

is] fascinating but also somewhat disquieting.'

Sydney Morning Herald

âRamona Koval has carved a reputation as a consummate book critic and interviewer. Her passion for storytelling and sharp analysis is turned inwards in

Bloodhound: Searching for My Father

, in which she asks herself: what is my life story? Her accessibly written forays into the science of DNA and familial lineages, and what makes us who we are, are beautifully intertwined with her meditations on identity and belonging⦠[

Bloodhound

is] an important reminder that history should never be forgotten.'

Books+Publishing

âShe's a shining presence in the world of literature, here in Australia and right across the globeâ¦Her voice is always recognisable, invigorating, familiar to us and greatly loved.'

Helen Garner

Ramona Koval is a Melbourne writer, journalist, broadcaster and editor. She is an honorary fellow in the Centre for Advancing Journalism at the University of Melbourne. From 2006 to 2011 she presented Radio National's

Book Show

, and she has written for the

Age

and

Australian

. She is the author of

By the Book: A Reader's Guide to Life

.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Ramona Koval 2015

The moral right of Ramona Koval to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Contains two extracts from Antelme, Robert.

The Human Race

. Trans. Jeffrey Haight & Annie Mahler. Evanston: The Marlboro Press / Northwestern University Press, 1998. Originally published in French in 1957 under the title

L'Espèce humaine

. Copyright © 1957 by Ãditions Gallimard, Paris. First published in English in 1992 by The Marlboro Press, Marlboro, Vermont. Translation copyright © 1992 by Jeffrey Haight & Annie Mahler. The Marlboro Press / Northwestern University edition published 1998 by arrangement with Ãditions Gallimard. All rights reserved.

First published in 2015 by The Text Publishing Company

This edition published in 2016

Book design by W. H. Chong

All photographs courtesy of the author

Typeset in Golden Cockerel ITC by J & M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Koval, Ramona, 1954â author.

Title: Bloodhound : searching for my father / by Ramona Koval.

ISBN: 9781925240900 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925095685 (ebook)

Subjects: Koval, Ramona, 1954âFamily. Holocaust survivors' familiesâAustralia.

Father and child.

Dewey Number: 929.20994

For my grandchildren,

and their children,

for ten generations

Contents

3. Something to find, something to see

7. The exact same shade as mine

10. The pregnant boy of Kazakhstan

13. A goatskin jacket and a bearskin hat

14. A good job in the infirmary

17. How do I look? What do they think?

And will the dead person have exercised his right to carry a secret to his grave? After all, is that not one of the great rights of life, to know that we know something that we will never reveal to anyone?

CARLOS FUENTES

Oif a meisseh fregt men kain kasheh nit.

Don't ask questions about fairytales.

YIDDISH PROVERB

For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge, increaseth sorrow.

ECCLESIASTES

1:18

DAD'S eightieth-birthday party was held late last century in his favourite restaurant, a cavernous space in a middle-class Melbourne suburb, with a tiled floor for easy cleaning, possibly even hosing down, and little in the way of warmth, charm or decoration. Clearly, you were here to eat until you were full.

Waiters balanced huge platters of food on their shouldersâgrilled meats and fish and salads and dips and bread, bread, breadâdelivering them to long tables of grandparents and their grandchildren, their daughters and sons-in-law, sons and daughters-in-law, and second and third cousins and their partners. The place forbade people from bringing their own drinksâinstead you got them at the bar, or had them delivered to the table after a lengthy delayâand each time the waiters ventured down the aisles they were accosted by ten burly customers, hands grabbing their shirts and threatening to unbalance the heaped trays.

My water! Where's my Diet Coke? I asked for a cappuccino! It's been ten minutes already and I'm dying of thirst!

Dad, on this, his day, had smuggled in orange juice and mineral water in a string bag. He'd stashed the bottles under his chair, from where he sneaked them out in full view of his grandchildren, his dark-brown eyes winking loudly: for if there can be such a thing as a winking noise, Dad had it in his repertoire. He was playing the big man, as my mother might have put it, a big shot with a string bagâas if this would fool anybody.

My mother's voice was in my ear, but not because she was sitting beside me. Her voice lived in my head. She had been dead for twenty-one years. She didn't make it to her fiftieth birthday, much less her eightieth. Each time Dad reached a new milestone I did the calculation. Why couldn't it be she who was celebrating, and he who was lying dead in the ground?

I know you're not supposed to wish people dead. Was it his fault that he had a new wife and a new life? They had been together for at least twenty-two yearsâanother calculation I would do, justifying my outrage on Mama's behalf. I have always been good at calculations.

Mama had found a photograph of a strange woman along with a small hand mirror. They had been secured by a rubber band to the underside of the sun visor on the passenger side of our family car, a white 1963 Ford Falcon that Mama and Dad were still driving in the mid-1970s. The woman was standing by a dark-green shrub, smiling at the photographer, who may have been Dad.

She was attractive, I remember thinking, much too attractive for him, surely, a short man with greying black hair slicked straight back from his forehead. The girlfriend, as we came to think of her, was several years older but more vital-looking than Mama, who'd had chronic myeloid leukaemia for a couple of years by then.

Mama tucked the photo back under the sun visor and I don't remember it being mentioned again, although she and Dad could have argued about it in Polish and I wouldn't have known. They had a long history of fighting but also of mind games. In our family album of often out-of-focus Box Brownie black-and-white photos (all of which seemed to have been taken a long way away from the subjects, so it was hard to see who they were and what they were doing) there were two photos of Dad with another man and two women, strangers to me, on a jaunt in an open-top sports car. I'd never seen a car like thatâI had no idea what they were doing together and who took the photo, why they were in the album and why Mama left them there.

He must have known she'd find the photo behind the sun visor. It was her car, too, and surely the rubber band in her eye line was a dead giveaway. Just as he must have known that everyone at the eightieth-birthday lunch would see his contraband drinks. He must have wanted them to.

Dad left Mama to set up house with the girlfriend, who later became his new wife, in January of the year of Mama's October death. It sounds bad. But most family stories are complicated.

My oldest nephew, then eleven, was sitting next to me at the birthday lunch. He was almost old enough to start preparing for his bar mitzvah, nearly a man, so he was allowed to taste the wine. I was teaching him to sip it slowly, to savour it. Not that I was an expert wine drinker. I don't really like its taste, preferring a shot of vodka. I agree with Ogden Nash that liquor is quicker.

Seeing this, his grandfatherâand after all, this was Dad's day, and why, he must have thought, shouldn't he be the centre of attentionâcalled out, âHey, sonny, watch this!' and downed a full glass of wine in three big gulps, then filled the glass to the top once more. I felt anger rise inside me as I watched him abrogate his grandfatherly duty to be wise and careful with the boy; to respect the wishes of his mother, my younger sister; and to support my gentle model-ling of responsible drinking. (These views on grandfatherly behaviour came from television and films, as I never met my grandparents.) How, I thought, and not for the first time, could the old man possibly be related to me?

Indeed, as I cast my eyes up and down the table, I observed, again not for the first time, that there seemed to be a meeting of two tribes here. There was the straight-haired, redheaded tribeâmy sister, her husband and two of their three childrenâand there was the taller, curly haired and blue-eyed tribe, my two daughters and me.

Any observer would have to sayâand they have, over the yearsâthat there was little physical evidence to link these people, except that they were all at this table, everyone except Dad fearing overeating and subsequent bloatedness, here to celebrate (while swearing under their breath to get this over and done with as quickly as possible) the eightieth birthday of this man, this short Jewish tailor from Poland, this survivor who was sent to the Treblinka death campâtwice, mind you, but that's another storyâand who spent nearly two years hiding in a âhole in the ground' with the Goldman brothers.

When I heard that phrase I thought of Dad as an animal, a rat or a fox, living in a burrow. How did you do that? Later I understood that they hid in a small cellar under the kitchen floor of a rural shack. But the image of him as a hunted thing, a night scavenger, stayed with me.

He was worried then, he once told me, that if he survived the war he would be an alcoholic after drinking daily the bootleg vodka they made from potato peelings, in part payment to the peasant who allowed them to hide there, despite the threat to his own life. How they manufactured the drink I never asked, and neither would you if you'd met the man, but there it was, his worry, and he'd tell us that the others taunted him for not wanting to drink, saying that teetotallers would wake up in the morning and know that was the best they were going to feel all day.