Blow Out the Moon (5 page)

Stewards bustled around, bringing blankets and snacks to the grown-ups and watching us suspiciously. Once, in a place where there was a little space, I skipped a few skips, and one shouted at me.

So, the deck was pretty boring. We decided to explore the rest of the ship. I ran down the first empty staircase we came to. No one stopped me. I ran back up, then ran down my favorite way. I grabbed the banister three steps below me tightly with one hand, then jumped SIX steps at once. I sort of run and jump and leap all at the same time — it’s almost like flying, with a short pause in between jumps to grab the banister again. Before the very bottom, you let go and bend your knees to land on the ground with a huge thud.

I ran back to the top and did it again: “Emmy, try running and jumping down more than one step at a time! Just grab the banister tightly and jump!” I said. “It’s really fun — like this, watch!”

She did; it WAS really fun and we both laughed a lot.

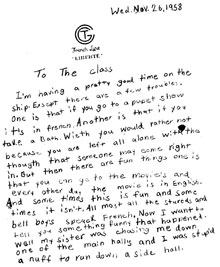

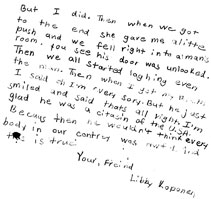

When we got sick of that, we explored. The ship was so big that there were lots of empty places — there just weren’t any on the deck itself. But BELOW the deck, there were stairs and ladders to climb up and down, and lots and lots of halls: wide ones (main halls) and narrower ones (side halls) and all of them had shiny, slippery floors, perfect for running and sliding and chasing each other. Here is a letter about it that I wrote to my class but never mailed:

I never found out where the man at our dining table was from, or whether he was a king or what. My mother said that it wouldn’t be polite to bring a map into the dining room so he could point to his country, and that it would be very rude to try to talk to him with sign language. But I DID learn why iron ships don’t sink — one of the bellboys told me. They’re not solid metal: they have huge spaces filled with air built into them — so much air that the ship becomes light enough to float on water, just as a big balloon attached to a basket full of people is light enough to float in the air. And even though I never found out anything about the king (or chieftain or prince), it was neat that people like that lived in the world and I had met one.

In London

When I woke up I didn’t know where I was at first. Then, I remembered: I was in London.

I looked around. My bed was in the corner, under the window. Emmy’s, Bubby’s, and Willy’s beds were in a row on the opposite wall.

The window was high on the wall, with black iron bars on it, and behind the bars a black iron fence with spaces between each pointed rod. There were no splotches of sun on the wall or the floor, just steady gray light and what little I could see of the sky (the room was in a basement) was gray, too.

“Emmy? Willy? Bubby?” I whispered.

The window and its view, as they looked from my bed.

They didn’t answer: still asleep, probably. They had all been asleep when we’d arrived, too: a grown-up named Jill who was going to be living with us had opened the door and helped carry them and our suitcases down to this room.

The suitcases were still on the floor, with their baggage tags on.

We’d carried them down the gangplank — even Willy carried one in the hand that wasn’t holding mine. The gangplank was exactly the same as the New York gangplank: just a short metal bridge with solid metal walls, painted the same creamy color as the deck walls.

But I could see right away that we were in a foreign country. The light was different — darker. It wasn’t just that it was a cloudy afternoon: The sky seemed heavier and closer to the ground than it did in America. I wasn’t sure I liked it. It was exciting, though, and it made me curious. As I said, “If even the SKY is different, just think what London will be like!”

I looked up again at the window in our bedroom: Outside, it looked like the day hadn’t even really started yet, it was so dark. The air felt damp, too, the way it does very early in the morning, before the sun comes up.

I got up and opened my suitcase, and then I decided to wake Emmy up. After all, it was our first day! She’d want to get ready for school early, too.

St. Vincent’s School

Jill, not my mother, took Emmy and Willy and me to school; Bubby stayed at home with my mother. (My mother had said we could stay home, too, but my father laughed and said there was no jet lag when you went on an ocean liner, and that he’d told the school we’d be there that morning.)

We didn’t walk: we went in a taxi — it was black, and square, and very old-fashioned.

I pressed my face to the window. London seemed old-fashioned, too. The sky was still dark gray, and most of the buildings, even the stores, looked like houses, not skyscrapers. Most were dirty-white — sometimes so dirty they were almost black — stone. There were lots of little parks; they looked wet and dark, too — dark green grass, bare dark trees.

The only colors were on the advertisements and buses. The buses were a bright, cheerful red, twice as tall as American buses. We’d seen them the night before, too (with both rows of windows glowing yellow), and my father said they were called “double-deckers.” I looked eagerly for more: I liked their color (bright red) and their shape, too. They were VERY cheerful.

The school looked just like the narrow, dirty-white houses on either side of it, except for a small metal sign that said: ST. VINCENT’S SCHOOL.

We went into a little hallway; two women were already standing there, smiling at us.

“I’m Mrs. Reed, the headmistress,” the older one said, still smiling. “And you’re the three little Americans. Who’s the eldest?”

I didn’t like her smile (too many teeth) or the way she talked (“

little

Americans”), but I answered.

“I am.”

“Come with me, dearie,” she said. “Miss Reed will sort out the others.”

None of us said a word. Emmy and I made a quick face at each other (she didn’t like the Reeds, either, I could tell). Willy stared after me with wide-open eyes: he looked horrified. I ran back and gave him a quick hug, and then I followed Mrs. Reed upstairs.

She opened a door and said to a roomful of children, “She’s new — from America.”

She left, and the children and I looked at each other.

They all wore white shirts and gray sweaters and navy-blue ties — even the girls had ties — and over the sweaters they had navy-blue jackets. The boys wore gray wool shorts and the girls wore skirts, and they all wore knee socks. The sweaters and skirts and shorts weren’t exactly the same, just the same colors; but all the jackets were exactly alike.

I was wearing a green plaid jumper.

“Do you live on a huge ranch?” a girl said eagerly.

“No.”

“Do you have your own gun?” a boy said. I could tell that he meant a real gun, not a toy. My six-shooter was in America, anyway, packed up in some box, because I’d brought

Grimm’s Fairy Tales

.

“No,” I said.

“Your own horse?”

“No.”

“Rum!” someone said.

I guessed that meant “weird” and I was right — I asked Jill about it later. I thought it was weird that they all acted as though America was like the Wild West on TV. Then an older boy with a thin face and blue-silver eyes (I guess they were mainly pale blue, with glints of silver) said, “What’s your name?”

“Libby. What’s yours?”

He didn’t answer. Instead, he laughed. One of the girls said Libby was “an odd sort of name.”

“Libby drink Libby’s!” the boy with the glinting eyes said, and laughed again.

The kids all started playing again and then an even older boy who was holding a little book said, “Can you spell?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Women,” he said.

“W-o-m-i-n,” I said.

“

E

-n,” he said, and everyone laughed. I realized that he had meant

Are you a GOOD speller?

I am a very bad speller, but you probably already know that from the letter I wrote on the

Liberté

.

No one else said anything to me, so I sat down and watched the kids running around until the teacher came in and the older boys went out and the other kids ran to their seats. They didn’t sit down: They stood straight behind them, as though they were in the army standing at attention.

So I stood at attention, too. The teacher raised her hand and they sang a song that had the same tune as “My Country ’Tis of Thee.” It went:

God save our gracious Queen,

Long live our noble Queen,

God save the Queen.

Send her victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us,

God save the Queen!

Then they sat down. They folded their hands, bent their necks, closed their eyes, and said, all together:

I am the child of God,

I ought to do his will,

I can do what he tells me to

And with his help I will.

Then they sat up and the teacher looked at me.

“You must be the American,” she said. “Come here, Elizabeth.” She gave me three little books — all very thin — an old-fashioned pen, and a bottle of ink. I was looking at the pen when she said it was time for spelling.

“Curious,” she said, and the girl next to me wrote in her little book. But when I tried to write in mine, my pen just made scratches on the paper.

“You must fill it UP!” the teacher said, and everyone laughed.

They were all looking at me, waiting.

I opened the pen: The bottom unscrewed, too, and inside it, attached to the point, was a little rubber tube. I dipped the point into the ink, then squeezed the tube gently — ink went in, you could see it and feel it filling the tube. When the tube was hard and full, I squished it — ink squirted out.

“Honestly, Elizabeth!” It was the teacher. She sounded annoyed. “Haven’t you ever seen a pen before?”