Blow Out the Moon (8 page)

Two of the dolls, as they looked when they were in the store.

But these were not like any dolls I’d ever seen — their faces had real expressions. They were about as long as my fingers: the children as long as my little finger, the grownups the size of my middle finger. We looked through the case for a long time, until the man behind it asked, very politely, if we’d like him to take any of the dolls out for us so we could “see them properly.” He talked to us just as though we were grown-up ladies and he was a grown-up gentleman — he almost bowed!

The doll Libby, when she was very old, almost falling apart — I took the picture while I was writing this book so you could see her.

We pointed to the ones we liked best, and he set them down on the counter and said we could hold them, and we thanked him and did hold them.

The legs AND arms bent and so did the bodies, so you could put them in any pose. Their feet were in metal shoes, so they didn’t bend, and their heads didn’t bend, but the necks did. They would even be able to RIDE. We looked and looked.

Finally, I picked out a boy with shorts and brown hair and kind of a sweet but mischievous expression. I decided to get him and a girl with a very short dress (yellow) and short curly brown hair. She had a sweet, wistful face. I got her and named her Emmy.

Emmy got a girl and a boy, too. The girl had kind of an angry expression, curly hair, and a white dress with red and blue lines that made squares. She was a little taller than my Emmy; Emmy named her girl Libby.

There was also a baby with long, curly blonde hair and a long pink nightgown — but we didn’t have enough money to get her, or any grown-ups (the grown-ups cost more, and besides, we could wait to get them). And the things they had to go WITH the dolls! All kinds of furniture, with drawers that really opened; a pink telephone with a tiny dialer that really turned. … But we could get them later; the important thing was that we had the dolls. I could hardly wait to get home and play with them.

Once we had the dolls, every day was fun — at least after school.

The mothers were both very frivolous: They spent all their time going shopping and talking about clothes and going to the theater. The fathers were very quiet and spent most of their time reading (we made books by cutting out the pictures of books advertised in magazines and pasting them onto folded-up paper). None of the parents paid any attention to the adventurous children, so the kids could do whatever they wanted.

THE BEST THINGS WERE:

• a wooden case about half the length of my little finger. The outside was polished, shining wood; inside, it was lined with green baize (that’s like velvet, only rougher) and divided into three tiny compartments holding tiny silver knives, spoons, and forks.

• a dark green wine bottle with a cork and a label you could really read. It came with a set of matching real glass wine glasses.

• a silver tray (real silver) with two real glasses.

• a silver-colored toaster with two pieces of toast: you could take the toast in and out, and there was a black rubber knob on the side that you pulled up and down to make the toast go in and pop out.

• a china tea set with tiny dark pink flowers on everything: a round tray, teapot, creamer, sugar bowl, and two cups and saucers. The flowers have faded away, so now it’s plain white.

There was also a crotchety old grandfather, who had black-and-white-checked trousers and a black tailcoat, a white beard, curly white hair, and glasses. He was very excitable (sometimes he got drunk and waved the green wine bottle around). There was also a doll with gray hair and a gray nurse’s uniform and a crabby face and wire glasses; she looked after the children when their parents were out, which was most of the time.

The parents and nurse all spoke in English accents (though since the fathers hardly ever talked, they didn’t really count). The grandfather’s accent was sort of English and sort of Scottish; the children all had American accents.

The dolls wrote letters to each other on tiny pieces of paper with tiny printing — we made envelopes by folding paper and then gluing the flaps. Usually the mothers wrote the letters.

A letter from one of the mother dolls to the other mother doll:

Darling: SUCH a bother! We’re going to a ball and I don’t have a THING to wear — I must go to London and get some new gowns. Would you like to come? Nursey can look after the children, of course. Ring me as soon as you get this: I hope the Post Office delivers it promptly. They’re getting so slow and lazy, like servants!

Your friend,

Sally Koponen.

I read their letters to each other out loud in the proper accent for the person. Then, after I’d read the letter out loud, the dolls would do something.

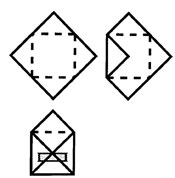

To make a doll envelope, cut a small square of paper, then fold in three of the corners and tape it, like this.

Our favorite was to have the two mothers go shopping or to the theater in London. Then the children could go into the forest, where they would always end up at the witch’s house. It was sort of like “Hansel and Gretel” (only the dolls were never tricked by the witch!). We knew that we were copying the story, but we still liked to do it. And we didn’t JUST copy, we made it funny. I think in the real story it’s funny when Hansel and Gretel eat the gingerbread house — that their first reaction when they see a house is to start eating it, especially when the bird has just told them not to! Our children did even funnier things.

“Hansel and Gretel,” from an old book.

Emmy was fun to play dolls with — we hardly ever played alone with each other in America, but she was different in London. She acted different — she never talked in baby talk or fake-cried, and she did funny things when we were working the dolls. (“Working” is what we called moving them and making them talk; of course, she worked her dolls and I worked mine.)

We wished and wished that the dolls were alive, and sometimes we pretended that they were alive and that they just ACTED like dolls. One day when I came home from school Emmy told me that she had sneaked back into our room very quietly and …

“I saw all the dolls running back to their places,” she said.

I wanted to believe her, and I almost did. I could picture Libby and Emmy running really fast and then lying down exactly where we had left them — but I knew it couldn’t be true. I wondered a lot if Emmy really thought it was, but I couldn’t ASK. It would be like asking someone if they still believed in Santa Claus. What if they did? So I didn’t say anything. And when, sometimes, she said, “That wasn’t where we left her!” I didn’t argue, either.

Anyway, everything was better after we got the dolls, even school; until the six months were almost up — and we found out we were staying in England for another year.

Something Big

When Daddy told us, Emmy and I could hardly believe it. We just looked at him, and then he said, “Aw, Em, don’t cry. It’s only a year.”

ONLY a year! ONLY! It was easy for

him

to say that! He loved London. But we hated it. Only a year! — as if he was asking us to wait fifteen minutes (though even that’s a long time when you want to go NOW). “Only a year.” What a stupid thing to say!

I ran to my room and slammed the door. ONLY a year!

Then, when I was sure no one could hear me, I did something I hardly ever do (and didn’t want to do then), because I was so disappointed and angry, too. ONLY a year! More than twice as long as we’d been here already before we could go home!

I was still crying when my mother came in to put the others to bed.

After she’d turned out the light, she came over to my bed. I could feel her sitting down on the edge of it before she gave my back a little pat.

“Do you hate it here that much?” she said in her gentlest voice. I didn’t answer; I can’t cry and talk at the same time. But I did make myself stop crying.

“Daddy and I thought you weren’t very happy in London. We’ve been thinking about that, and talking to our friends here, and we thought you might be happier in the country. How would you like to go to a boarding school in the country?”

I thought of all the books about girls going to boarding school. It DID sound fun — and exciting, too.

I sat up.

“Could Emmy come too?”

“Well — six is a little young for boarding school,” my mother said.

“She’s almost seven. And in

The Girls of Rose Dormitory

the heroine’s little sister was only five and she was at the school. So were other kids her age.” (Though they were called “the babies.”)

But when I asked Emmy, she didn’t want to go, even when I told her that some schools in the stories had their own horses and the girls could ride them.

“That’s in a book, not real life,” she said.

“Things that happen in books happen in real life, too!” I said. “I bet that IS true!”

“Well even if it is I think we should all stay together.”

But the more I thought about it, the better I liked the idea of going. Boarding school DID sound fun in the stories, and almost anything would be better than London. And if I found a really good school, one with horses, Emmy might change her mind. As my mother said, “Maybe when she’s a little older.”

My mother and I had lots of time to talk because it was vacation (they called it the Easter holidays even though it wasn’t Easter yet), and we went to look at boarding schools almost every day.

They were empty, because it was the holidays, so of course that made them different from the books. But they didn’t LOOK like the schools in the books, either, or at least not at all the way I had imagined those schools.

In real life, the rooms were little, and dark; and the people who showed us around were so old!

And then suddenly spring came.

Spring in England is different — maybe you have to live through an English winter to understand it. The days lengthen, far more than they do in America, and the sky is bright, bright blue, not gray. The air feels soft and clean, you can smell damp earth and see leaves sparkling in the sun wherever you go.

It still rained, but there was sun every day.

When I opened my eyes one morning, there was even sun on my bed, and that was the day my mother and I went to look at the Brighton School for Girls. Brighton, my mother told me, was a seaside town. When we got off the train, the air was sparkling and smelled like salt; and at the school — which was a very short walk from the sea — all the windows and the white front door sparkled in the sun.