Blue Highways (20 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

“That’s what I heard in Selma.”

“I’m not alone, but sometimes it seems like a conspiracy. Especially in little towns. Gossip and bigotry—that’s the blood and guts.”

“Was that person who just looked out the window white?”

“Are you crazy? Nobody on this end of Margaret Street is white. That’s what I mean about us blacks not working together. Half this town is black, and we’ve only got one elected black official. Excuse my language, but for all the good he does this side of the bayou, he’s one useless black mofo.”

“Why don’t you do something? I mean you personally.”

“I do. And when I do, I get both sides coming down on me. Including my own family. Everywhere I go, sooner or later, I’m in the courtroom. Duplicity! That’s my burning pot. I’ve torn up more than one court of law.”

We sat down at her small table. A copy of

Catch-22

lay open.

“Something that happened a few years ago keeps coming back on me. When I was living in Norristown, outside Philadelphia, I gained a lot of weight and went to a doctor. She gave me some diet pills but never explained they were basically speed, and I developed a minor drug problem. I went to the hospital and the nuns said if I didn’t sign certain papers they couldn’t admit me. So I signed and they put me in a psychiatric ward. Took two hellish weeks to prove I didn’t belong there. God, it’s easy to get somebody adjudicated crazy.”

“Adjudicated?”

“You don’t know the word, or you didn’t think I knew it?”

“It’s the right word. Go on.”

“So now, because I tried to lose thirty pounds, people do a job on my personality. But if I shut up long enough, things quiet down. Still, it’s the old pattern: any nigger you can’t control is crazy.”

As we ate our sandwiches and drank Barq’s rootbeer, she asked whether I had been through Natchitoches. I said I hadn’t.

“They used to have a statue up there on the main street. Called the ‘Good Darkie Statue.’ It was an old black man, slouched shoulders, big possum-eating smile. Tipping his hat. Few years ago, blacks made them take it down. Whites couldn’t understand. Couldn’t see the duplicity in that statue—duplicity on

both

sides. God almighty! I’ll promise them one thing: ain’t gonna be no more gentle darkies croonin’ down on the levee.”

I smiled at her mammy imitation, but she shook her head. “In the sixties I wanted that statue blown to bits. It’s stored in Baton Rouge now at LSU, but they put it in the wrong building. Ought to be in the capitol reminding people. Preserve it so nobody forgets. Forgives, okay—but not forgets.”

“Were things bad when you were a child?”

“Strange thing. I was born here in ’forty-one and grew up here, but I don’t remember prejudice. My childhood was warm and happy—especially when I was reading. Maybe I was too young to see. I don’t know. I go on about the town, but I love it. I’ve put my time in the cities—New Orleans, Philly. Your worst Southern cracker is better than a Northern liberal, when it comes to duplicity anyway, because you know right off where the cracker crumbles. With a Northerner, you don’t know until it counts, and that’s when you get a job done on yourself.”

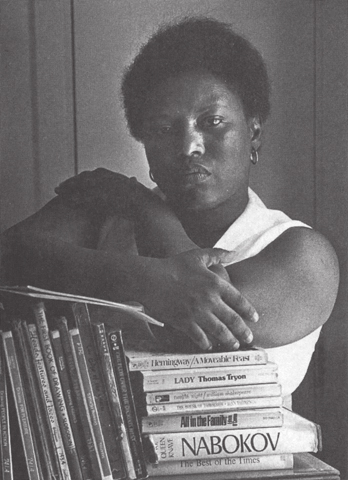

8. Barbara Pierre in St. Martinville, Louisiana

“I’d rather see a person shut up about his prejudices.”

“You haven’t been deceived. Take my job. I was pleased to get it. Thought it was a breakthrough for me and other blacks here. Been there three weeks, and next Wednesday is my last day.”

“What happened?”

“Duplicity’s what happened. White man in the shop developed a bad back, so they moved him inside. His seniority gets my job. I see the plot—somebody in the company got pressured to get rid of me.”

“Are you going to leave town?”

“I’m staying. That’s my point. I’ll take St. Martinville over what I’ve seen of other places. I’m staying here to build a life for myself and my son. I’ll get married again. Put things together.” She got up and went to the window. “I don’t know, maybe I’m too hard on the town. In an underhanded way, things work here—mostly because old blacks know how to get along with whites. So they’re good darkies? They own their own homes. They don’t live in a rat-ass ghetto. There’s contentment. Roots versus disorder.” She stopped abruptly and smiled. “Even German soldiers they put in the POW camp here to work the cane fields wanted to stay on.”

We cleared the table and went to the front room. A wall plaque:

OH LORD, HELP ME THIS DAY

TO KEEP MY BIG MOUTH SHUT.

On a bookshelf by the window was the two-volume microprint edition of the

Oxford English Dictionary,

the one sold with a magnifying glass.

“I love it,” she said. “Book-of-the-Month Club special. Seventeen-fifty. Haven’t finished paying for it though.”

“Is it the only one in town?”

“Doubt it. We got brains here. After the aristocracy left Paris during the French Revolution, a lot of them settled in St. Martinville, and we got known as

Le Petit Paris

. Can you believe this little place was a cultural center only second to New Orleans? Town started slipping when the railroad put the bayou steamers out of business, but the church is proof of what we had.”

“When you finish the college courses, what then?”

“I’d like to teach elementary school. If I can’t teach, I want to be a teacher’s aide. But—here’s a big ‘but’—if I can make a living, I’ll write books for children. We need black women writing, and my courses are in journalism and French. Whatever happens, I hope they don’t waste my intelligence.”

She went to wash up. I pulled out one of her books:

El Señor Presidente

by Guatemalan novelist Miguel Asturias. At page eighty-five she had underlined two sentences: “The chief thing is to gain time. We must be patient.”

On the way back to the agency, she said, “I’ll tell you something that took me a long time to figure out—but I know how to end race problems.”

“Is this a joke?”

“Might as well be. Find a way to make people get bored with hating instead of helping. Simple.” She laughed. “That’s what it boils down to.”

T

HE

Corps of Engineers calls it the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System. Some Acadians call it a boondoggle in the boondocks. The Atchafalaya River, only one hundred thirty-five miles long, has an average discharge more than twice as great as that of the Missouri River although the area it drains is less than a fifth of the Missouri’s and the Big Muddy is nearly twenty times as long. Yet, the Atchafalaya forms the biggest river basin swamp in North America, and before it became an overflow drain, its swamp was at least as biologically rich and varied as the Everglades. Maybe it still is, despite claims by older Cajuns that wildlife isn’t what it was a generation ago. Nevertheless, some ornithologists believe the swamp might hold the last ivory-billed woodpecker.

After the great flood of 1927, the Corps built hundreds of miles of “protection levees” around the upper Atchafalaya and down the length of the basin to create an “emergency discharge” route for the Mississippi and Red rivers. The Corps said had it done nothing to the Atchafalaya, the Mississippi—always trying to change course—would eventually open a new channel about sixty miles north of St. Martinville and leave New Orleans on a backwater oxbow.

The problem is that engineers built so injudiciously, the swamp is filling with some of the one million tons of silt the big rivers carry in daily; and those Cajuns who traditionally make a living from the wetlands by fishing, frogging, mudbugging, trapping, and mosspicking are having to leave their fastness and take work in industry. The Corps altered not just the Atchafalaya and a great swamp but also one of the distinctive ethnic peoples in America.

Maybe the swamp is doomed anyway, what with bayous being dredged and channels dug so oil and gas drilling equipment can get in, what with pipelines being laid, and wipe-out logging of cypress and tupelo. To be sure, dry-land farmers—a minority—are happy. At the north end of the basin, they have cleared sixty thousand acres of swamp hardwoods for pasturage and soybeans.

Now, to rectify their errors, the Corps wants permanent control of the basin, and, of all things, many environmentalists support the plan. Everyone believes what the dredge and bulldozer can do, they can also undo; but a Cajun named Cassie Hebert told me he had yet to see a bush-hog make a mink.

Some Cajuns believe in only one thing—the Mississippi. Hebert said: “The Atchafalaya’s a shorter way to the Guff than the Missippi take. Big river gonna find us down here, Corps be damned. One day rain gonna start and keep on like it do sometimes. When the rainin’ stop, the Missippi gonna be ninety miles west of N’Orleans and St. Martinville gonna be a seaport. And it won’t be the firstest time the river go runnin’ from Lady N’Orleans.”

Indian legend tells of a serpent of fabulous dimension living in the Atchafalaya basin; when Chitimacha braves slew it, its writhing throes gouged out Bayou Teche.

Teche

may be an Indian word for “snake,” and Cajuns say the big river will one day avenge the serpent. We have only to wait.

The Teche, at the western edge of the basin and paralleling the Atchafalaya, has been spared the salvation wreaked on the river, even though, before roads came, the little Teche—not the Atchafalaya—was the highway from the Gulf into the heart of Louisiana. Half of the eighteenth-century settlements in the state lay along or very near the Teche: St. Martinville, Lafayette, Opelousas, New Iberia. The Teche was navigable for more than a hundred miles. Indians put dugouts on it; Spanish adventurers and French explorers floated it in cypress-trunk pirogues (some displacing fifty tons); settlers rode it in keelboats pulled by mules or slaves; merchandise arrived by paddlewheelers; and during the Civil War, Union gunboats came up the Teche to commandeer the fertile cane fields along its banks. All of this on a waterway no wider than the length of a war canoe, no deeper than a man, no swifter than mud turtles that swim it.

Blue road 31, from near Opelousas, follows the Teche through sugarcane, under cypress and live oak, into New Iberia. St. Martinville had dozed on the bayou for two hundred years. Not so New Iberia. A long strip of highway businesses had cropped up to the west, and the town center by the little drawbridge was clean and bright. No dozing here. Bayouside New Iberia gave a sense of both the new made old and the old made new: contemporary architecture interpreting earlier designs rather than imitating them; a restored Classic Revival mansion, Shadows on the Teche; a society whose members are hundred-year-old live oaks; and the only second-century, seven-foot marble statue of the Emperor Hadrian in a savings and loan. New Iberia suggested Cajun history, but St. Martinville lived it.

I took Louisiana 14: roadsides of pink thistle, cemeteries jammed with aboveground tombs, cane fields under high smokestacks of sugar factories, then salt-dome country, then shrimp trawlers at Delcambre. My last chance at Cajun food was Abbeville, a town with two squares: one for the church, one for the courthouse. On the walk at Black’s Oyster Bar a chalked sign:

FRESH TOPLESS SALTY OYSTERS.

Inside, next to a stuffed baby alligator, hung an autographed photo of Paul Newman, who had brought the cast of

The Drowning Pool

to Black’s while filming near Lafayette. Considering that a recommendation, I ordered a dozen topless (“on the halfshell”) and a fried oyster loaf (oysters and hot pepper garnish heaped between slices of French bread). Good enough to require a shrimp loaf for the road.

On the highway, I wished the British had exiled more Acadians to America if only for their cooking. Somewhere lives a bad Cajun cook, just as somewhere must live one last ivory-billed woodpecker. For me, I don’t expect ever to encounter either one.

The rice fields began near Kaplan, where the land is less than twenty feet above the sea only thirty miles south, and kept going all the way to Texas. The Lake Arthur bridge made a long, curvilinear glide into space as it rose above the water; passage was like driving the chromium contours of Louisianan Jose de Rivera’s famous “Construction 8.” At Lake Charles, another sinuous parabola of bridgeway, an aerial thing curving about so I could see its underside as I went up.

The city stretched below in a swelter of petrochemical plants and wharves. I got through only with effort and pressed north to state 27. When I had left home, I announced a stop, sooner or later, at a cousin’s in Shreveport. I hoped for mail. U.S. 171 was traffic, fumes, heat, grim faces. I became a grim face and drove. Rosepine, Anacoco, Hornbeck, and Zwolle—alphabetically, the last town in the Rand McNally

Road Atlas

(Abbeville, just south, is the first).

A yellow simmer of glaring haze sat on Shreveport like a pot lid. I pulled in at a honky-tonk called Charlie’s to telephone my cousin. No one home. I took a seat at the bar. Charlie’s was built-in-spare-time-after-bowling-league construction, the ceilings so low I could almost touch them flatfooted. After ten minutes I regained my vision in the cool darkness. Near the bar hung one of those pictures of dogs playing poker and cheating in a multitude of cleverly canine ways. The west fire exit unexpectedly opened and sunlight poured in; like Draculas before the cross, we cried out and covered our eyes.