Blue Highways (22 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

At the counter I drank a Royal Crown; the waitress dropped my quarter into the cash register, a King Edward cigarbox. Forks and knives clinked on plates behind a partition at the rear. It was too much. I ordered a dinner.

She set down a long plate of ham, beans, beets, and brown gravy. I seasoned everything with hot peppers in vinegar. From the partition came a

thump-thump

like an empty beer bottle rapping on a table. The waitress pulled two Lone Stars from the faded cooler, foam trickling over her fingers as she carried them back. In all the time I was there, I heard a voice from the rear only once: “I’m tellin’ you, he can flat out thow that ball.”

A man came from the kitchen, sat beside me, and began dropping toothpicks through the small openings of Tabasco sauce bottles used as dispensers. Down the counter, a fellow with tarnished eyes said, “Is it Tuesday?” The waitress nodded, and everything fell quiet again but for the clinking of forks. After a while, a single

thump,

and she carried back a single Lone Star. The screendoor opened; a woman, old and tall, stepped into the dimness cane first, thwacking it to and fro. Loudly she croaked, “Cain’t see, damn it!”

A middle-aged woman said, “Straight on, Mother. It isn’t that dark.” She helped the crone sit at one of the tables. They ordered the meal.

“Ain’t no use,” the waitress said. “Just sold the last plate to him.”

Him was me. They turned and looked. “Let’s go, Mother.” The tall woman rose, breaking wind as she did. “Easy, Mother.”

“You don’t feed me proper!” she croaked and thwacked out the door.

The man with the Tabasco bottles said to no one in particular, “Don’t believe the old gal needed any beans.”

Again a long quiet. Then the one who had ascertained the day said to the waitress, “Saw a cat runned over on the highway. Was it yourn?”

She shifted the toothpick with her tongue. “What color?” He couldn’t remember. “Lost me an orange cat. Ain’t seen Peewee in a week.”

“I got me too many cats,” he said. “I’ll pay anybody a quarter each to kill my spares.”

That stirred a conversation on methods of putting away kittens, and that led to methods of killing fire ants. The man beside me put down a toothpick bottle. It had taken some time to fill. He said, “I’ve got the best way to kill far ants, and it ain’t by diggin’ or poison.” No one paid attention. Finally he muttered, “Pour gasoline into the hive.” No one said anything.

“Do you light it?” I asked.

“Light what?”

“The gasoline.”

“Hell no, you don’t light it.” He held out a big, gullied palm and pointed to a tiny lump. “Got nipped there last year by a far ant. If you don’t pick the poison out, it leaves a knot for two or three years.”

The other man talked of an uncle who once kept sugar ants in his pantry and fed them molasses. “When they fattened up, he put them on a butter sandwich. Butter kept them from runnin’ off the bread.” The place was so quiet you could almost hear the heat on the tin roof. If anyone was listening to him, I couldn’t tell. “Claimed molasses gave them ants real flavor,” he said.

Thump-thump.

The woman turned from the small window, her eyes vacant, and went to the cooler for two more bottles of Lone Star.

I walked to the post office for stamps. The postmistress explained the town name. A century ago the custom was to drop a letter and ten cents for postage into the pickup box. That was in Old Dime Box up on the San Antonio road, now Texas 21. “What happened to Old Dime Box?”

“A couple houses there yet,” she said, “but the railroad came through in nineteen thirteen, three miles south, so they moved the town to the tracks—to here. Now the train’s about gone. Some freights, but that’s it.”

“I see Czech names on stores.”

“We’re between Giddings and Caldwell. Giddings is mostly German and Caldwell’s mostly Czech. We’re close to fifty-fifty. Whites, that is. A third of Dime Box is black people.”

“How do the different groups get along?”

“Pretty well. We had a to-do in the sixties over integration, but it was mostly between white groups arguing about who had the right to run the schools. Some parents bussed kids away for a spell, but that was just anger.”

“Bussing in Dime Box?”

“City people don’t think anything important happens in a place like Dime Box. And usually it doesn’t, unless you call conflict important. Or love or babies or dying.”

T

HE

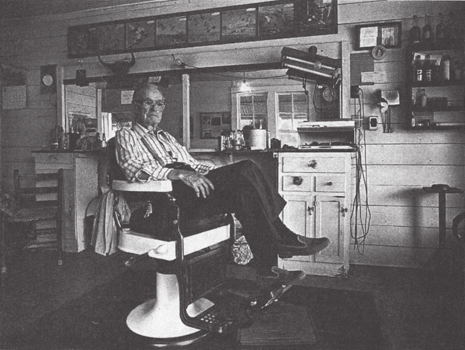

big bass had a pair of horns, and beneath it, the barber of Dime Box dozed in his chair. He woke when I stopped in front of the long, open windows to look at the trophy on his wall. “Texas bull bass,” he said. “More bull than bass.” It was so craftily assembled I couldn’t see how he’d done it. “I caught the fish and mounted it to the steer horns. Kids come in to stare. Spooks them. Don’t know why nature never put horns on a fish.”

“Or fins on a longhorn?” I needed a trim. “Just nip the ends.”

“One of them no-ears cuts. Took an ear off a week back—didn’t see it.”

I trusted that was a joke. I hadn’t paid $1.50 for a haircut in a decade. The old clock in Claud Tyler’s barbershop had stopped at two-ten, and in the center of the room stood an iron woodstove, now assisted by a small gas one. Above the sink were bottles of Lucky Tiger hair tonic. I’d forgotten about tonics.

“Where you hail from, bub?” he said.

“Same place your Lucky Tiger’s made.”

He stepped away from the chair to look me over closely. “Ever know a feller named Wendell Thompson from up in Missouri? Called him ‘Hop’?”

I said I didn’t. Several other times he asked if I knew So-and-so from up my way, each time giving the moniker: Beep, Cherry, Pard, Tinbutt.

“Hop lived in the county awhile. I and him was in the Fox and Wolf Hunters Association. Now that was a bunch of fellers. I had a history of the Association. Plumb interesting. The mother-in-law burned it up.”

He took from the wall a framed panoramic photograph of a group of men in hunting garb and laid it across my lap. The picture was a good three feet long, and there must have been a hundred men standing or kneeling in a field, with a beagle here and about. “Can you find me?”

I tried four or five times. I think it disheartened him that I couldn’t recognize a younger Tyler. “Have I changed that much?” He pointed himself out and then brought a worn copy of a Texas hunting magazine with several photographs of men around campfires. I looked carefully and took a chance.

“Hell, that’s Raymond Mueller. Called him ‘Dipper.’ This one’s me.”

“I see it now. How could I miss it? Got a bad eye.”

“Hooey. That’s before I started fading away. I had an aneurism removed, and I just ain’t the man I was. I can abide that, but take you, you’re a stranger, and all you see is a seventy-six-year-old man. I wasn’t always like this. That’s what hurts—people forget what you been.” He stepped away from the chair again. “Listen to me. I used to cut hair and press suits all day then go out and hunt half the night. Now I just talk a big stick. Only thing that don’t run down is your mouth.”

9. Claud Tyler in Dime Box, Texas

“What’s that about pressing suits?”

“Come here.” I followed him to a small backroom, the striped chaircloth still around my neck, hair half cut. He pointed to an old steam press.

“Sold the dry-cleaning machine, but there’s where I put a million creases in pants. Started in nineteen twenty-five. Feller would come in for a shave, haircut, and suit pressing. All for thirty-five cents. This was as good a shop as any in Texas. And I did a business. Listened to a million stories cutting those old squirrels’ heads. Barber’s the third most lied-to person, you know.”

“Who’s first?”

“Man’s wife is first anywhere in the world. Priest is second.”

We went back to the chair, and he took more snips. “Used to barber across the street. West of Sonny’s. Oughta go see the rattlesnake skins in there.” He motioned south, and for a moment I thought I would have to cross the street with a half-cut head to look at Sonny’s rattlesnakes. “Been in this shop since the forties. Built it myself. How many barbers left that built their own shops?”

“Saw some figures on it. I think it was three—not counting you.”

Tyler smiled. “Come here.” I followed him to the side window where a big cottonwood grew from under the edge of the wooden building. It had started to lift the floor. “Tree’s old as the shop. Cut it down once a year for six years. Finally gave up. I’ll be gone before it turns the place over. Filled in that west side with river sand when I built the shop. Musta took in a seed.” We went back to the chair. “Gotten old watching that tree grow. It’s so cussed fixed on making its way, I’ve thought about pulling the shop down to give it room. Kind of living memorial to shade-tree barbering. Ain’t much need of a barbershop in Dime Box now. People get out to the bigger towns anymore.”

“A lot of small towns are coming back.”

“Could happen to us. They located a big pool of oil here—deep oil. Way down. Feller picked up some land for back taxes, turned around and discovered oil. Now people believe oil’s gonna bring things back like they used to be. I say hoping’s swell, but better be ready for it to go as fast as it comes. Who listens? People thought the railroad wouldn’t ever play out neither. That’s why they moved the town here. We used to say there’d always be the railroad. You could count on it because it don’t depend on weather and weevils don’t eat steel. Well, bub, how’d you like our depot?”

“I haven’t seen it.”

“Tore down, that’s why. But Model T’s used to line up all along the road to the depot. Cars, trains, girls in big hats. Dime Box made noise then.”

“Freights still come through, don’t they?”

“Can’t live off a toot and a whistle unless you can eat steam. Hell, it ain’t even steam anymore. We get on now with ranching, farming, people stopping off on the way to the artificial lake.”

“Artificial?” I imagined a giant plastic pond, the height of Disney World fool-the-eye stuff.

“Lake Somerville. One of those dam lakes.” He whisked away the hair with his little white brush. “Before the cattle business got big in here, we used to grow cotton—even had a gin. All gone. When I was a whippersnapper, I used to look at the cotton fields and wonder which boll would end up in my shirt. Now shirts are this polyester made from oil. But I reckon when we go to pumping oil, Dime Box will be back in the shirt business, and they’ll call that progress.”

He started to dress me down with Lucky Tiger. “Leave it dry if you would.”

“You young fellers take all the fun out of barbering. I’da got run out of town thirty years ago for a haircut like that.”

To me, it was the best haircut I ever got in Dime Box, Texas.

T

HE

wooden floor creaked, the bar warped in the middle; the rattlesnake skins nailed to the wall, and the stuffed bobcat, and deer trophy heads, all looked parched. Even the ceiling supports, peeled cedar trunks with lopped branches, had split in the dry Texas air. In Sonny’s Place was a dusty upright piano, dusty because the entertainment at Sonny’s wasn’t music. It was dominoes. Of the six domino tables, each with a complement of worn tiles, only the one nearest the bar had a game that afternoon. A man in a yellow cap that said

CAT

twice announced he was playing his last round; he said it before the first last game and again before the second last game.

A large old fellow walked in, greeted everyone, sat at the bar, ordered a glass of Pearl, drank it off in two tilts, licked the foam from his upper lip, looked at me, gave a smile that pinned his great jowls to his ears, and said, “Good!” I nodded. He watched me, and I could tell he was getting ready to ask in his own manner for my version of the human saga. As if playing in an old Western, he actually said, “What brings you to Dime Box?”

I told him I was on a long motor tour, but he was a little hard of hearing, and I had to repeat twice to get the right volume. The whole tavern turned to ears; perhaps the old gentleman pretended hearing problems in order to share stories with everyone—after all, a new story was a thing of value in Sonny’s. I felt like a radio, but I got used to the little audience at the domino table.

The man’s name was, as I understood it, Mr. Valca, and he’d been born in Dime Box in the last century. Some voices I’d heard in town carried slight old-world accents, but his was pronounced. All

w

’s came out as

v

’s, and his lips had never known the sound of

th

. His parents had emigrated from Czechoslovakia, and he learned English only after beginning school. He reminisced about his Slavic past.

“In see Great Var against see Germans, you remember vee Americans fight vis see Poles and Roossians against see evil,” he said. “Here vas me, a poor boy from Dime Box, Texas, talking vis see foreign soldiers in sair langvage. See city boys—Chicago and Cleveland—even say vas amazed. Vee Slavs all understand each ozzer. Ohh! Vee haff some good times, me and soze Slavs! Vee play cards, not see dominoes, and vee trink see slivovitz. Sat vas a var!”

Once he had been a clothing merchant. “But I might haff done ozzer sings too.” He drank a second beer, this one more slowly. “Are you pheelosopher?”