Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History of S) (21 page)

Authors: David Hitt,Heather R. Smith

Tags: #History

Astronaut Hank Hartsfield recalled those moments of silence from the perspective of someone on the ground. “It was an exciting time for me when we flew that first flight, watching that and seeing whether we was going to get it back or not,” he said. “Of course, we didn’t have comm all the way, and so once they went

LOS

[loss of signal] in entry was a real nervous time to see if somebody was going to talk to you on the other side. It was really great when John greeted us over the radio when they came out of the blackout.”

Continued Crippen,

I deployed the air data probes around Mach 5, and we started to pick up air data. We started to pick up

TACAN

s [Tactical Air Control and Navigation systems] to use to update our navigation system, and we could see the coast of California. We came in over the San Joaquin Valley, which I’d flown over many times, and I could see Tehachapi, which is the little pass between San Joaquin and the Mojave Desert. You could see Edwards, and you could look out and see Three Sisters, which are three dry lake beds out there. It was just like I was coming home. I’d been there lots of times. I did remark over the radio that, “What a way to come to California,” because it was a bit different than all of my previous trips there.

Young flew the shuttle over Edwards Air Force Base and started to line up for landing on Lake Bed 22. Crippen recalled,

My primary job was to get the landing gear down, which I did, and John did a beautiful job of touching down. The vehicle had more lift or less drag than we had predicted, so we floated for a longer period than what we’d expected, which was one of the reasons we were using the lake bed. But John greased it on.

Jon McBride was our chase pilot in the

T

-38. I remember him saying, “Welcome home, Skipper,” talking to John. After we touched down, John was . . . feeling good. Joe Allen was the CapCom at the time, and John said, “Want me to take it up into the hangar, Joe?” Because it was rolling nice. He wasn’t using the brakes very much. Then we got stopped. You hardly ever see John excited. He has such a calm demeanor. But he was excited in the cockpit.

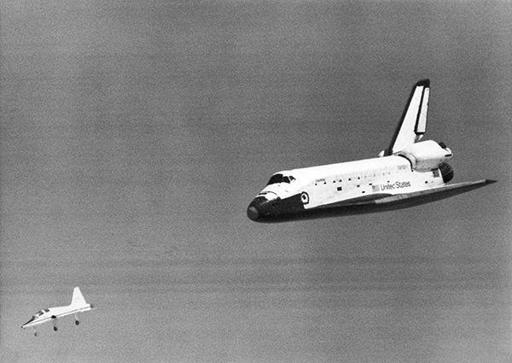

16.

The Space Shuttle

Columbia

glides in for landing at the conclusion of

STS

-1. Courtesy

NASA

.

On the ground, the crew still had a number of tasks to complete and was to stay in the orbiter cockpit until the support crew was on board. “John unstrapped, climbed down the ladder to the mid-deck, climbed back up again, climbed back down again,” recalled Crippen.

He couldn’t sit still, and I thought he was going to open up the hatch before the ground did, and of course, they wanted to go around and sniff the vehicle and make sure that there weren’t any bad fumes around there so you wouldn’t inhale them. But they finally opened up the hatch, and John popped out. Meanwhile I’m still up there, doing my job, but I will never forget how excited John was. I

completed my task and went out and joined him awhile later, but he was that excited all the way home on the flight to Houston, too.

Crippen’s additional work after Young left the orbiter meant that the pilot had the vehicle to himself for a brief time, and he said that those postflight moments alone with

Columbia

were another memory that he would always treasure.

CapCom Joe Allen recalled the reaction in Mission Control to the successful completion of the mission.

When the wheels stopped, I was very excited and very relieved. . . . I do remember that Donald R. Puddy, who was the entry flight director, said, “All controllers, you have fifteen seconds for unmitigated jubilation, and then let’s get this flight vehicle safe,” because we had a lot of systems to turn down. So people yelled and cheered for fifteen seconds, and then he called, “Time’s up.” Very typical Don Puddy. No nonsense. . . . Other images that come into my head, the people there that went out in the vans to meet the orbiter wear very strange looking protective garments to keep nasty propellants that a Space Shuttle could be leaking from harming the individuals. These ground crew technicians look more like astronauts than the astronauts themselves. Then the astronauts step out and in those days, they were wearing normal blue flight suits. They looked like people, but the technicians around them looked like the astronauts, which I always thought was rather amusing.

Terry Hart was CapCom during the launch of

STS

-1, but he said watching the landing overshadowed his launch experience. The landing was on his day off and he had no official duties, yet he watched from the communications desk inside Mission Control. “When the shuttle came down to land, I had tears in my eyes,” said Hart. “It was just so emotional. On launch, typically you’re just focused on what you have to do and everything, but to watch the

Columbia

come in and land like that, it was really beautiful and it was kind of like a highlight. Even though I wasn’t really involved, I could actually enjoy the moment more by being a spectator.”

Astronaut John Fabian recalled thinking during the landing of that first mission just how risky it was.

The risk of launch is going to be there regardless of what vehicle you’re launching, and the shuttle has some unique problems; there’s no question about that. But this

is the first time; we’ve never flown this thing back into the atmosphere. We don’t have any end-to-end test on those tiles. The guidance system has only been simulated; it’s never really flown a reentry. And this is really hairy stuff that’s going on out there. And the feeling of elation when that thing came back in and looked good—the landing I never worried about, these guys practice a thousand landings, but the heat of reentry, it was something that really, really was dangerous.

While the mission was technically over, the duties of the now-famous first crew of the Space Shuttle were far from complete. The two would continue to circle the world, albeit much more slowly and closer to the ground, in a series of public relations trips. “The

PR

that followed the flight I think was somewhat overwhelming, at least for me,” Crippen said. “John was maybe used to some of it, since he had been through the previous flights. But we went everywhere. We did everything. That sort of comes with the territory. I don’t think most of the astronauts sign up for the fame aspect of it.”

In particular, he recalled attending a conference hosted by

ABC

television in Los Angeles very shortly after the flight.

All of a sudden, they did this grandiose announcement, and you would have thought that a couple of big heroes or something were walking out. They were showing all this stuff, and they introduced John. We walk out, and there’s two thousand people out there, and they’re all standing up and applauding. It was overwhelming.

We got to go see a lot of places around the world. Did Europe. Got to go to Australia; neat place. In fact, I had sort of cheated on that. I kept a tape of “Waltzing Matilda” and played it as we were coming over one of the Australian ground stations, just hoping that maybe somebody would give us an invite to go to Australia, since I’d never been there. But that was fun.

Prior to

STS

-1, Crippen recalled, the country’s morale was not very high. “We’d essentially lost the Vietnam War. We had the hostages held in Iran. The president had just been shot. I think people were wondering whether we could do anything right. [

STS

-1] was truly a morale booster for the United States. . . . It was obvious that it was a big deal. It was a big deal to the military in the United States, because we planned to use the vehicle to fly military payloads. It was something that was important.”

Crippen said

STS

-1 and the nation’s return to human spaceflight provided a positive rallying point for the American people at the time, and

human space exploration continues to have that effect for many today. “A great many of the people in the United States still believe in the space program,” he said. “Some think it’s too expensive. Perspective-wise, it’s not that expensive, but I believe that most of the people that have come in contact with the space program come away with a very positive feeling. Sometimes, if they have only seen it on

TV

, maybe they don’t really understand it, and there are some negative vibes out there from some individuals, but most people, certainly the majority, I think, think that we’re doing something right, and it’s something that we should be doing, something that’s for the future, something that’s for the future of the United States and mankind.”

6.

The Demonstration Flights

With the return of

Columbia

and its crew at the end of

STS

-1, the first flight was a success, but the shuttle demonstration flight-test program was still just getting started. Even before

STS

-1 had launched, preparations for

STS

-2 were already under way. The mission would build on the success of the first and test additional orbiter systems.

STS

-2

Crew: Commander Joe Engle, Pilot Dick Truly

Orbiter:

Columbia

Launched: 12 November 1981

Landed: 14 November 1981

Mission: Test of orbiter systems

STS

-1 had been a grand experiment, the first time a new

NASA

human launch vehicle made its maiden flight with a crew aboard. Because of that, the mission profile was kept relatively simple and straightforward to decrease risk. Before the shuttle could become operational, however, many more of its capabilities would have to be tested and demonstrated. In that respect, the mission of

STS

-2 began long before launch.

“One of the things I remember back then on

STS

-2,” recalled astronaut Mike Hawley,

when they mate the shuttle to the solid rocket motor on the external tank in the Vehicle Assembly Building [

VAB

, at Kennedy Space Center in Florida], they do something called the shuttle interface test, . . . making sure the cables are hooked up right and the hydraulic lines are hooked up properly and the orbiter and the solids and all of that functions as a unit before they take it to the pad. In those days we manned that test with astronauts, and for

STS

-2 the astronauts that manned it were me and Ellison Onizuka. We were in the

Columbia

in the middle of the night hanging on the side of the

ET

[external tank] in the

VAB

going through this test.

Part of the test, Hawley explained, involved making sure that the orbiter’s flight control systems were working properly, including the moving flight control surfaces, the displays, and the software.

It turns out when you do part of this test and you bypass a surface in the flight control system, it shakes the vehicle and there’s this big bang that happens. Well, nobody told me that, and Ellison and I are sitting in the vehicle going through this test, and I forget which one of us threw the switch, but . . . there’s this “bang!” and the whole vehicle shakes. We’re going, “Uh-oh, I think we broke it.” But that was actually normal. I took delight years later in knowing that was going to happen and not telling other people, so that they would have the same fun of experiencing what it’s like to think you broke the orbiter. . . . That was a lot of fun. Except for flying, that was probably the most fun I ever had, was working the Cape job.

In contrast to

STS

-1, commanded by

NASA

’s senior member of the astronaut corps,

STS

-2 was the only demonstration flight to be commanded by a “rookie” astronaut—Joe Engle, who had earned air force astronaut wings on a suborbital spaceflight on the

X

-15 rocket plane.

Engle’s path to becoming the shuttle’s first

NASA

-unflown commander began about a decade earlier, when he lost out on a chance to walk on the moon. Engle had been assigned to the crew of

Apollo 17

, alongside commander Gene Cernan and command module pilot Ron Evans. However, pressure to make sure that geologist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt made it to the moon cost Engle his slot as the

Apollo 17

Lunar Module pilot. When Engle was informed that he was being removed from the mission, Deke Slayton discussed with him options for his next assignment.

“I wouldn’t say I was able to select, but Deke was very, very good about it and asked me, in a one-to-one conversation, not promising that I would be assigned to a Skylab or not promising I would be assigned to the Apollo-Soyuz mission, but implying that if I were interested in that, he would sure consider that very heavily,” Engle recalled.

He also indicated that the Space Shuttle looked like it was going to be funded and looked like it was going to be a real program. At the time, I think I responded something to the effect that it had a stick and rudder and wings and was an airplane and was kind of more the kind of vehicle that I felt I could contribute

more to. And Deke concurred with that. He said, “That was my opinion, but if you want to fly sooner than that, I was ready to help out.” I think Deke was happy that I had indicated I would just as soon wait for the Space Shuttle and be part of the early testing on that program.