Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History of S) (22 page)

Authors: David Hitt,Heather R. Smith

Tags: #History

The decision meant that Engle was involved in the very beginnings of the shuttle program, even before the contractors and final design for the vehicle had been selected.

Rockwell and McDonnell Douglas and Grumman were three of the primary competitors initially and had different design concepts for the shuttle, all pretty much the same, but they were significantly different in shape and in configuration for launch, using different types of boosters and things. I was part of that selection process only as an engineer and a pilot and assessing a very small part of the data that went into the final selection. But it was interesting. It was very, very interesting, and it, fortunately, allowed me to pull on some of the experience that I had gotten at Edwards in flight-testing, in trying to assess what might be the most reasonable approach to either flying initial flights, data-gathering, and things of that nature.

Engle and

STS

-2 pilot Richard Truly served as the backup crew for

STS

-1 and trained for that mission alongside Crippen and Young. Not long after the first mission was complete, a ceremony was held in which Engle and Truly were presented with a “key”—made of cardboard—to

Columbia

. “I think the hope was that would be a traditional handover of the vehicle to the next crew,” Engle recalled.

It was a fun thing to do. In fact, I think it was done at a pilots’ meeting one time, as I recall. John and Crip handed Dick and I the key, and I think there were so many comments about buying a used car from Crip and John that it became more of a joke than a serious tradition, and I don’t recall that it really lasted very long. I think it turned from cardboard into plywood, and I don’t recall that it was done very long after that. Plus, once we got the next vehicles,

Discovery

,

Challenger

, on line, it lost some significance as well. You weren’t really sure which vehicle you were going to fly after that, so you didn’t know who to give the key to.

In the wake of the tile loss on the first shuttle mission, a renewed effort was made to develop contingencies to deal with future problems and, according to Engle, additional progress was made.

Probably the biggest change that occurred was more emphasis on being able to make a repair for a tile that might have come off during flight. John and Crip lost a number of tiles on

STS

-1. Fortunately, none were in the critical underside, where the maximum heat is. Most of them were on the

OMS

pod and on the top of the vehicle. But the inherent cause of those tiles coming loose and separating was not really understood, and on

STS

-2 we were prepared to at least try to fill some of those voids with

RSI

[Reusable Surface Insulation], the rubbery material that bonds the tile to the surface itself. So in our training, we began to fold in

EVA

training, using materials and tools to fill in those voids.

Exactly seven months after the launch of

STS

-1, the launch date for the second Space Shuttle mission arrived. Sitting on the launchpad, Engle was in a distinctive position—on his first

NASA

launch, he would be returning to space. It would, however, be a very different experience from his last; he was actually going to stay in orbit versus just briefly skimming space, as he had in the

X

-15. In fact, he said, while his thoughts on the launchpad did briefly touch on his previous flights on the

X

-15, space wasn’t the place he was thinking about returning to. Instead, he was already thinking ahead to the end of the mission.

As I recall, the only conscious recollection to the

X

-15 was that at the end of the flight we would be going back to Edwards and landing on the dry lake bed. And I think, for all of the training and all of the good simulation that we received, that’s where I felt the most comfortable, the most at home, going back to Edwards. And at the end of the flight, when we rolled out on final approach going into the dry lake bed, that turned out to really be the case. It was a demanding mission and there were a lot of strange things that went on during our first flight, but when we got back into the landing pattern, it just felt like I was back at Edwards again, ready to land another airplane.

According to Engle, the launch was very much like it had been in the simulators. However, even though the first shuttle mission had provided real-world data on what an actual flight would be like, there were still, at the time the

STS

-2 crew was training, ways in which the simulators still did not fully capture the details of the ascent. The thing that most surprised him during launch was “the loud explosion and fireball when the solid rocket boosters were ejected. That was not really simulated very well in the simulator, because I don’t think anybody really anticipated it would be quite as impressive a show as that. I don’t remember that [John and Crip] mentioned it to us, but that caught our attention, and I think we did pass that on in briefings to the rest of the troops, not just to [the

STS

-3 crew], but to everyone else who was flying downstream.”

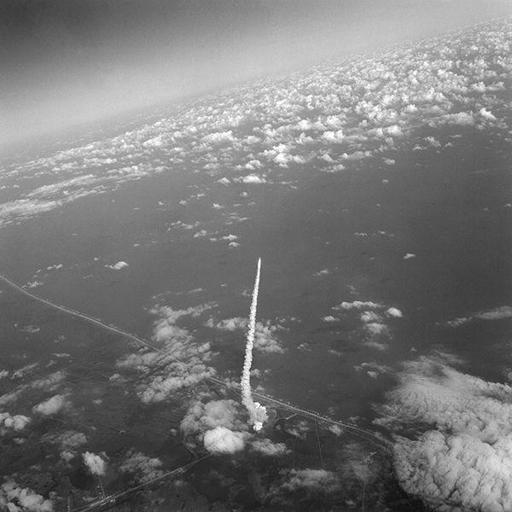

17.

An aerial view of the launch of

Columbia

on the second Space Shuttle mission,

STS

-2. Photo taken by astronaut John Young aboard NASA’s Shuttle Training Aircraft. Courtesy

NASA

.

If the launch was relatively nominal, things changed quickly after that. Two and a half hours into flight,

Columbia

had a fuel cell failure, which, under mission rules, required an early return to Earth—cutting the mission from 125 hours to 54. “We were disappointed,” Engle said.

As I recall, we kind of tried to hint that we probably didn’t need to come back, we still had two fuel cells going, but at the time, it was the correct decision, be

cause there was no really depth of knowledge as to why that fuel cell failed, and there was no way of telling that it was not a generic failure, that the other two might follow. And, of course, without fuel cells, without electricity, the vehicle is not controllable. So we understood and we accepted. We knew the ground rules; we knew the flight rules that dictated that if you lost a fuel cell, that it would be a minimum-time mission. We had really prepared and trained hard and had a full scenario of objectives that we wanted to complete on the mission. Of course, everybody wants to complete everything.

In fact, according to Engle, the only real disappointment he and Truly felt at the time was that, after investing so much training time into preparing for the mission goals, they weren’t going to have the time to fully accomplish them. “I don’t think we consciously thought, ‘Well, we’re not going to have five days to look at the Earth.’ I don’t think that really entered our minds right then, because we were more focused on how we are going to get all this stuff done.”

Rather than accept defeat, Engle and Truly managed to get enough work done even in the shortened duration that the mission objectives were declared 90 percent complete at the end of the flight. “We were able to do it because we had trained enough to know precisely what all had to be done, and we prioritized things as much as we could,” Engle explained.

Fortunately, we didn’t have

TDRSS

[Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System] at the time. We only had the ground stations, so we didn’t have continuous voice communication with Mission Control, and Mission Control didn’t have continuous data downlink from the vehicle either, only when we’d fly over the ground stations. So when our sleep cycle was approaching, we did, in fact, power down some of the systems and we did tell Mission Control goodnight, but as soon as we went

LOS

, loss of signal, from the ground station, then we got busy and scrambled and cranked up the remote manipulator arm and ran through the sequence of tests for the arm, ran through as much of the other data that we could, got as much done as we could during the night. We didn’t sleep that night; we stayed up all night. Then the next morning, when the wakeup call came from the ground, why, we tried to pretend like we were sleepy and just waking up.

After the flight, I remember Don Puddy saying, “Well, we knew you guys were awake, because when you’d pass over the ground station, we could see you were drawing more power than you should have been if you were asleep.” But that was about the only insight they had into it.

The first use of the robot arm was one of the major ways that

STS

-2 moved forward from

STS

-1 in testing out the vehicle. “From the beginning we had the

RMS

, the remote manipulator system, the arm, manifested on our flight, and that was a major test article and test procedure to perform, to actually take the arm, to de-berth the arm and take it out through maneuvers and attach it to different places in the payload to demonstrate that it would work in zero gravity and work throughout its envelope. Dick became the primary

RMS

-responsible crew member and did a magnificent job in working with the arm people.”

The premission training for testing the arm included working with its camera and figuring out what sort of angles it could capture. Truly learned that the arm could be maneuvered so that the camera pointed through the cabin windows of the orbiter. Once they were in orbit, Truly took advantage of this discovery by getting shots of himself and Engle in the cabin, with Truly displaying a sign reading “Hi, Mom.”

Sally Ride, who was heavily involved in the training for the arm, also worked with the crew to help develop a plan for Earth observations during the mission. “They were both very, very interested in observing Earth while they were in space, but they weren’t carrying instruments other than their eyes and their cameras,” Ride said.

They wanted to have a good understanding of what they would be seeing, what they should look for, and what scientists wanted them to look for. The crew had to learn how to recognize the things that scientists were interested in: wave patterns on the surface of the ocean, rift valleys, large volcanoes, a variety of different geological features on the ground. I spent quite a bit of time with the scientists, as a liaison between the scientists and the astronauts who were going to be taking the pictures, to try to understand what the scientists had observed and then to help the astronauts understand how to recognize features of interest and what sort of pictures to take.

During the flight, not only was the crew staying extra busy to make up for the lost time, but CapCom Terry Hart recalled an incident in which the ground unintentionally made additional, unnecessary work for the crew.

It turned out that President Reagan was visiting Mission Control during the

STS

-2, and it was just [over eight months] after he had been shot. . . . This was one of his first public events since recovering from that. Of course, everyone was

very excited about that, and it turned out he was coming in on our shift. . . . Mission Control was kind of all excited about the president coming and everything. He came in, and I was just amazed how large a man he was. I guess

TV

doesn’t make people look as large as they sometimes are. And I was on comm, so I was actually the one talking to the crew at that time when he came in. So I had the chance then to give him my seat and show him how to use the radios, and then I actually introduced him to the crew. I said something to the effect that, “

Columbia

, this is Houston. We have a visiting CapCom here today.” I said, “I guess you could call him CapCom One.” And then the president smiled and he sat down and had a nice conversation for a few minutes with the crew.

While the event was a success and an exciting opportunity for the astronauts, Mission Control, and the president, Hart recalled that it was later discovered that a miscommunication had caused an unintended downside to the uplink.

We didn’t realize we had not communicated properly to the crew, and the crew thought this was going to be a video downlink opportunity for them. . . . They had set up

TV

cameras inside the shuttle to show themselves to Mission Control while they were talking to the president, when the plan was only to have an audio call with the president, because the particular ground station they were over at that time didn’t have video downlink. We had wasted about an hour or two of the crew’s time, so we kind of felt bad about that.

We didn’t learn about that until after. . . . It all worked out and everything, but it just shows you how important it is to communicate effectively with the crews and to work together as a team and all. And of course, most of the crews, the astronauts, they’re all troopers. They want to do their very best, and if Mission Control is not careful, you’ll let them overwork themselves.

The extra time the crew members gained by not sleeping at night allowed them to be more productive, but the lost sleep, and a side-effect problem related to the failed fuel cell, caught up with them as the mission neared its end. The membrane that failed on the fuel cell allowed excess hydrogen to get into the supply of drinking water. “So we had very bubbly water,” Truly said.